Review of the RCMP's Policies and Procedures Regarding Strip Searches

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act

Subsection 45.34(1)

Table of Contents

- Results in Brief

- Recommendations

National Personal Search Policy

Divisional Personal Search Policies

- British Columbia ("E" Division) Strip Search Policy

- Saskatchewan ("F" Division) Strip Search Policy

- Northwest Territories ("G" Division) Strip Search Policy

- Alberta ("K" Division) Strip Search Policy

Mandatory RCMP Strip Search Training

- Cadet Training at Depot Division

- National Training

- RCMP Divisional Strip Search Training

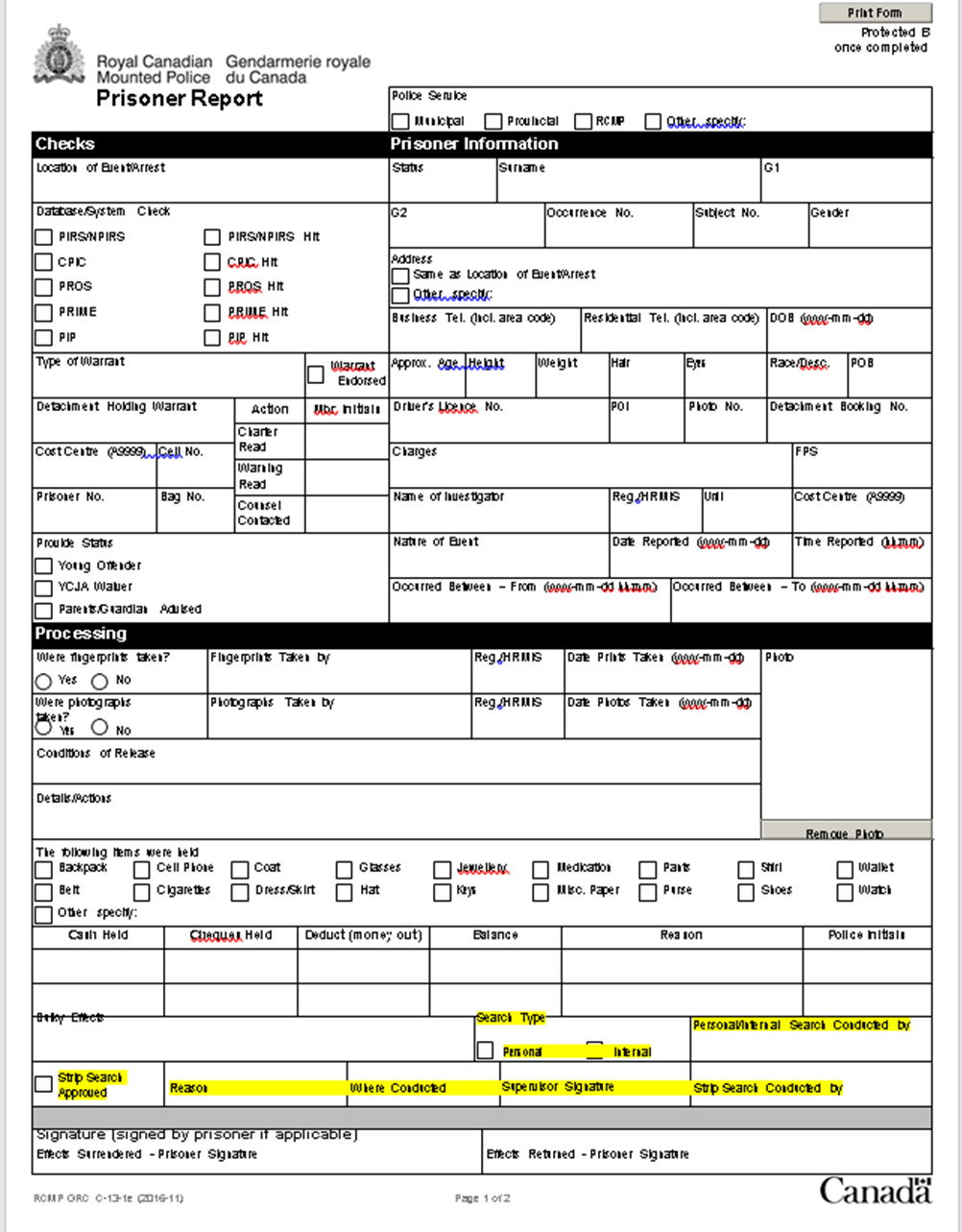

- Prisoner Report Form

- Surrey Detachment Strip Search Policy Advisory

- Mental Health Act and Vulnerable Prisoners

RCMP Implementation of the 2017 Final Report Recommendations

Appendix 1 – Mandate and Methodology

- Mandate

- Methodology

Appendix 3 – National and Divisional Policies

- National Headquarters Operational Manual Chapter 21.2 - Personal Search

- Divisional Policies

Related Links

- Chairperson's Statement

October 1, 2020 - Commissioner's Response

October 1, 2020 - Systemic Review Terms of Reference

March 2018 - Final Report into Policing in Northern British Columbia (2017)

February 16, 2017

List of Detachments Reviewed

“E” Division

British Columbia

- Burnaby

- Kamloops

- Prince George

- Surrey

“K” Division

Alberta

- Lloydminster

“F” Division

Saskatchewan

- North Battleford

- Prince Albert

“G” Division

Northwest Territories

- Yellowknife

“J” Division

New Brunswick

- Moncton

- Oromocto

- Bathurst

“M” Division

Yukon

- Whitehorse

“V” Division

Nunavut

- Iqaluit

Executive Summary

The Supreme Court of Canada noted in its landmark 2001 decision R v Golden that strip searches are "inherently humiliating and degrading,"Footnote 1 albeit justified in certain circumstances. Given the potential for violations of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, clear policies, adequate training, and appropriate supervision should guide police officers.

Following concerns raised by civil liberties groups, in 2013 the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP ("the Commission") undertook a review of RCMP policing in northern British Columbia, including an examination of personal searches (strip searches).

That review found significant shortcomings in the RCMP's personal search policies (which include strip searches), inadequate training, and insufficient means of tracking strip search data for purposes of compliance review and enhancing transparency and accountability.

The Final Report into Policing in Northern British ColumbiaFootnote 2 (hereinafter "the Final Report") contained ten Recommendations related to personal searches, all of which the RCMP Commissioner supported.

In 2018, the Commission initiated this current reviewFootnote 3 to examine:

- the degree to which the RCMP implemented the relevant Final Report Recommendations;

- the adequacy, appropriateness, sufficiency, and clarity of RCMP policies and training related to personal searches (strip searches in particular); and

- whether the RCMP is complying with policy and has the means to evaluate compliance.Footnote 4

Results in brief

Changes to the RCMP's personal search policies following the 2017 Final Report resulted in significant improvements. That said, further amendments are necessary to enhance the clarity of these policies and ensure consistency with current relevant jurisprudence.

The Commission found that the RCMP's national personal search policy (including cell block searches) is unclear and inadequate, and that divisionalFootnote 5 policies pertaining to strip searches are either inadequate or inappropriate, often due to their reliance on national policy.

The Commission also identified ongoing issues with policy compliance, including:

- inadequate articulation and file documentation of the grounds for a strip search;

- inadequate supervision and supervisory review of files;

- inadequate training of members and supervisors; and

- the practice of routinely removing and/or searching a prisoner's undergarments, which is inconsistent with RCMP strip search policies and relevant jurisprudence.

It is apparent from the Commission's review that many members are not adequately aware of RCMP personal search policies. Moreover, the only mandatory RCMP training regarding personal search policies is that provided by the RCMP to cadets during their basic training, which the Commission finds inadequate. There is no mandatory national or divisional training for members or supervisors; rather, they learn on the job.

The Commission is particularly concerned with the inadequate supervision of members, lack of articulation on files, and overall lack of knowledge of what constitutes a strip search at the Iqaluit Detachment. Interviews revealed that bras are routinely removed and searches are video-recorded.

In contrast, the Commission did identify good practices at some detachments to encourage policy compliance and provide adequate guidance.

In assessing the implementation of the 2017 Final Report Recommendations, the Commission found that the RCMP has adequately implemented seven of the ten Recommendations. However, the RCMP has not acted on the Recommendations to provide additional training for cadets and members, nor has it amended its policy to include an appropriate means to record, track and assess compliance.

In the Commission's view, the inability of the RCMP to evaluate and report on policy compliance negatively affects its overall accountability, as it does not facilitate internal or independent review. In that regard, the Commission's review was hampered by the RCMP's document management and storage practices, and required a manual review of prisoner reports and occurrence reports in an effort to identify those that included a strip search.

Recommendations

The Commission makes eleven Recommendations to improve the RCMP's national and divisional policies as well as its training and supervision, and to enhance transparency and accountability.

The Commission believes that the Recommendations contained in this report, including some based on existing RCMP good practices, will result in enhanced member compliance with the relevant policies and jurisprudence.

Findings and Recommendations

Policy Findings

Finding No. 1: RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" remains inadequate. In particular:

- section 3.1.2.2.1., in reference to the removal of undergarments, is unclear;

- section 3.1.2.4., regarding investigative purposes, is unclear;

- section 5.1., as it relates to the removal of items prior to detainees being lodged in cells, is unclear; and

- sections 5.2. and 5.3., regarding the search and removal of a prisoner's bra, are inadequate, inappropriate, and inconsistent with established jurisprudence.

Finding No. 2: Although significant improvements have been made to the amended policy, by virtue of its reliance on RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2., "E" Division's policy related to strip searches is inadequate.

Finding: No. 3: "F" Division policy section 5.3., directing members to have a second member present during a strip search, is inadequate, inappropriate, and inconsistent with established jurisprudence.

Finding No. 4: "G" Division policy sections 1.3. and 2.2. provide inappropriate and inadequate direction, and are inconsistent with established jurisprudence.

Finding No. 5: By virtue of its reliance on RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2., "K" Division’s strip search policy is inadequate, insufficient, and unclear.

Training Findings

Finding No. 6: Strip search training at Depot Division is inadequate and insufficient, as it has not been enhanced to ensure that RCMP cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, policies, and procedures.

Finding No. 7: RCMP mandatory national training for members and supervisors in relation to strip searches does not exist.

Finding No. 8: RCMP divisions do not have mandatory training for members and supervisors in relation to strip searches.

Compliance Finding

Finding No. 9: RCMP national and divisional personal search policies do not address an appropriate means of recording and tracking strip searches, or assessing compliance to facilitate internal or independent review.

Detachment Finding

Finding No. 10: The Iqaluit Detachment has significant member non-compliance with the RCMP's personal search policy and the relevant jurisprudence.

Supervision Finding

Finding No. 11: The overall supervision of members conducting strip searches, and the subsequent supervisory file review for policy compliance, was inadequate in most of the detachments examined by the Commission.

Findings and Recommendations with Respect to the Implementation of

the Relevant Recommendations Found in the Final Report into

Policing in Northern British Columbia

Finding No. 12: The RCMP's implementation of Recommendations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 regarding national and BC divisional policy is adequate.

Finding No. 13: The RCMP's implementation of Recommendations 7, 8, and 9 regarding training and independent review is inadequate.

Policy Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1: That the RCMP amend National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" to ensure adequacy, appropriateness, clarity, and consistency with established jurisprudence.

Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP revise divisional policies subsequent to making the recommended amendments to National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search."

Training Recommendations

Recommendation No. 3: The Commission reiterates its 2017 Recommendation that Depot Division enhance basic training, including scenario-based training (online or in person), to ensure that cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, and relevant policies and procedures for all types of personal searches.

Recommendation No. 4: That the RCMP introduce divisional-level mandatory training to ensure that members are cognizant of the legal requirements, policies, and procedures for strip searches, and that the RCMP include this training in the Operational Skills Maintenance Re‑Certification.

Compliance Recommendation

Recommendation No. 5: The Commission reiterates its 2017 Recommendation that the RCMP amend its national and divisional Operational Manual policies on personal searches to enhance transparency and accountability, by ensuring that policies include an appropriate means of recording, tracking, and assessing compliance, thus facilitating internal evaluation and independent review.

Operational Guidance Recommendations

Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP, particularly in Nunavut, provide operational guidance to members with respect to the handling of vulnerable persons detained (as it relates, for example, to mental health issues and self-harm), and that it consider providing trauma‑informed training.

Recommendation No. 7: That RCMP divisions provide operational guidance to members regarding strip search policies, proper articulation of the required reasonable grounds, documentation of the manner in which the search took place, and proper documentation of supervisory approval.

Supervision Recommendation

Recommendation No. 8: That the RCMP develop specific supervisor training regarding duties and responsibilities in accordance with National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search."

Good Practice Recommendations

Recommendation No. 9: That the RCMP consider the Prince George RCMP Detachment's cell block Operational Manual ("PRISONERS: Guarding Prisoners/Personal Effects") and Prisoner Report form ("Prisoner Report – Personal Searches [Strip Searches]") as good practice for relevant detachments Force-wide.

Recommendation No. 10: That the RCMP consider providing relevant detachments with copies of the "Strip Search Policy Advisory" poster utilized at the Surrey RCMP Detachment.

Closed-Circuit Video Recommendation

Recommendation No. 11: That the RCMP provide clearer direction to divisions regarding the use of closed-circuit video equipment during strip searches in order that members do not infringe on the Charter rights of the person being searched.

Introduction

In Canada, the police have statutory and common law authorities to conduct personal searches, including strip searches. Although a frisk search is relatively non-intrusive, a strip search is highly intrusive, humiliating, and dehumanizing.

Given the inherent and substantial risk of violating individual protections afforded by section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms ("Charter"), the Supreme Court of Canada, in R v Golden,Footnote 6 outlined the limited and prescribed circumstances under which police can conduct a strip search. The Court further indicated that this extreme police power could not be undertaken as a matter of routine.

The burden is on the police to justify the strip search and ensure that it is carried out in a reasonable manner. The Supreme Court went so far as to establish guidelines for the police to consider in conducting a strip search, as the manner in which it is conducted informs whether the search is reasonable.

Adherence to the eleven safeguards is required to execute a lawful search. As such, many police services in Canada, including the RCMP, incorporated the Supreme Court guidelines into their respective operational policies.

Given the level of intrusiveness and the impact strip searches have on individuals, the Commission initiated a review of the RCMP's strip search policies and procedures in 2018, following up on the 2017 Final Report.

Specifically, the Commission conducted a review and reported its Findings and Recommendations with respect to the RCMP's policy, the Force's compliance to the policy and its ability to evaluate it, the training provided, as well as the degree to which the RCMP implemented the ten Recommendations from the northern British Columbia review.

The mandate and methodology are outlined in Appendix 1 of this report.

National Personal Search Policy

The RCMP's national policy—Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search"—addresses different types of search:

- personal search (i.e. frisk);

- strip search;

- internal search (i.e. body cavity search), and

- cell block search.

For the purposes of this investigation, the Commission focused on strip searches and cell block searches. The policy review set out to determine whether the RCMP's current national policy is adequate, appropriate, sufficient and clear. The review also considered the degree to which the RCMP has implemented the Commission's Recommendations contained in the 2017 Final Report (see Appendix 1) regarding this policy.

In reaching its conclusions, the Commission relied on the national personal search policy (see Appendix 3), the RCMP Commissioner's Response to the Interim Report,Footnote 7 member interviews,Footnote 8 the framework set out in paragraph 101 (questions 1 through 11) of Golden, as well as other relevant jurisprudence (see Appendix 2).

Section 1 of the RCMP's national policy includes definitions regarding the various types of personal searches. The Commission found the definitions to be sufficiently clear to allow members to differentiate between the types of searches. In addition, these definitions are unambiguous and consistent with current, relevant jurisprudence.

The Commission concludes that, by including these unambiguous definitions in its national personal search policy, the RCMP has adequately implemented Recommendation 1 in the Commission's Final Report, which is that the RCMP update its National Headquarters Operational Manual definitions to eliminate ambiguity and ensure that the definitions are consistent with current jurisprudence.

Section 2 of the RCMP's national policy on personal searches includes general guidance to members. In the Commission's opinion, sections 2.4., 2.5., and 2.6. provide clear and sufficient direction, and are consistent with the questions raised in paragraph 101 of Golden. The emphasis on strip searches not being a routine police procedure is appropriate, as are the references to the grounds required for a strip search, and the requirement that it be conducted by a member of the same sex as the detainee, absent exigent circumstances, which are adequately referenced in section 2.6.

Sections 2.5. and 2.6. pertain to Recommendation 3 in the Commission's Final Report, which called on the RCMP to amend its national personal search policy so that it clarifies when a strip search of the opposite sex is permitted and articulates the circumstances or criteria that must be met before conducting or overseeing a strip search. The Commission concludes that the RCMP has adequately implemented Recommendation 3.

Section 3. of the RCMP's national policy regarding personal searches provides direction with respect to members' roles and responsibilities. In the Commission's opinion, section 3.1.1.1.1. provides members with clear and adequate direction that is consistent with question 4 in paragraph 101 of Golden ("Has it been ensured that the police officer(s) carrying out the strip search are of the same gender as the individual being searched?").

In addition, section 3.1.1.1.2. provides members with adequate and clear direction that is consistent with question 5 in Golden ("Will the number of police officers involved in the search be no more than reasonably necessary?").

Section 3.1.1.1.3. of the policy appears to have been amended in response to Recommendation 10 of the Commission's Final Report, which is that the RCMP amend previous national policy on personal searches to include specific guidance and direction in relation to strip searches of youth.

The Commission concludes that the RCMP's implementation of Recommendation 10 is adequate. The RCMP has amended its national policy on personal searches to include clear and specific guidance and direction in relation to strip searches of youth.

Section 3.1.2. pertains specifically to strip searches. Section 3.1.2.1. provides clear and sufficient direction for members to follow the leading relevant, settled case law when conducting a strip search.

Section 3.1.2.2.1. provides direction for members to obtain proper supervisor authorization prior to conducting a strip search, absent exigent circumstances.

This section was adequately amended in response to Recommendation 2 of the Commission's Final Report, which called on the RCMP to ensure a more robust supervisory oversight, and is consistent with question 3 set out in paragraph 101 of Golden ("Will the strip search be authorized by a police officer acting in a supervisory capacity?").Footnote 9 However, the note referencing the removal of undergarments is not clear, as it suggests that the removal of undergarments is separate from strip searches, which is inconsistent with Golden.

Section 3.1.2.2.2. provides clear instructions that are consistent with relevant jurisprudence, specifically Golden, paragraph 101, question 8 ("Will the strip search be conducted as quickly as possible and in a way that ensures that the person is not completely undressed at any one time?").Footnote 10

The national strip search policy goes on to provide direction to members about how and where they should conduct a strip search. In the Commission's opinion, sections 3.1.2.2.3., 3.1.2.2.4., 3.1.2.3., and 3.1.2.5. provide members with clear and sufficient guidance that is consistent with the framework outlined in paragraph 101 of Golden:

- Question 1 – "Can the strip search be conducted at the police station and, if not, why not?"

- Question 2 – "Will the strip search be conducted in a manner that ensures the health and safety of all involved?"

- Question 7 – "Will the strip search be carried out in a private area such that no one other than the individuals engaged in the search can observe the search?" and

- Question 11 – "Will a proper record be kept of the reasons for and the manner in which the strip search was conducted?"Footnote 11

The framework established in paragraph 101 of Golden includes question 5: "Will the number of police officers involved in the search be no more than is reasonably necessary in the circumstances?" In that regard, section 3.1.2.4., when read in conjunction with section 3.1.1.1.2., provides reasonably clear direction to prevent the unnecessary presence of members during a strip search.

Nevertheless, based on information obtained during the Commission's interviews, there is some ambiguity regarding the circumstances that would permit the presence of more than one member during a strip search. Therefore, the Commission believes that it would be beneficial to amend section 3.1.2.4. in a manner that provides additional direction with respect to the investigative purposes, or other circumstances in which it would be reasonably necessary for more than one member to be present during a strip search.

The Commission notes that section 3.1.2.5., which directs members who are conducting strip searches to make "accurate, detailed notes of the authorization, the reasons for the strip search, and the manner in which it was conducted," appears to have been amended in response to Recommendation 5 in the Commission's Final Report.

This section provides clear and sufficient direction that is consistent with question 11 in paragraph 101 of GoldenFootnote 12 as well as other settled jurisprudence that stresses the importance of the police keeping proper records of the reasons for the strip search and the manner in which it was conducted. The Commission concludes that the RCMP has adequately implemented Recommendation 5.

Sections 3.1.2.6. and 3.1.2.6.1. of the policy directs members to have a detainee run their hands vigorously through their hair to show that nothing is hidden on their scalp, if there are no police safety concerns. In the Commission's view, having the detainee handling their own hair ensures the health and safety of all involved, as well as minimum force necessary to conduct the strip search. This aligns with question 2 ("Will the strip search be conducted in a manner that ensures the health and safety of all involved?") and question 6 ("What is the minimum of force necessary to conduct the strip search?") listed in paragraph 101 of Golden.

Moreover, the Commission is of the opinion that subsections 1 and 2 of section 3.1.2.6.2., which advise members to direct detainees to move/manipulate their own body parts until the members are satisfied upon inspection that nothing has been concealed, are clear and consistent with paragraph 101 of Golden.

Specifically, they are in line with question 2 ("Will the strip search be conducted in a manner that ensures the health and safety of all involved?"), question 6 ("What is the minimum of force necessary to conduct the strip search?"), and question 9 ("Will the strip search involve only a visual inspection of the arrestee's genital and anal areas without physical contact?").

In Recommendation 4 of its Final Report, the Commission recommended that the RCMP amend its internal search policy to ensure that it clearly specifies the requisite grounds for an internal search as well as the approvals required prior to conducting the search.

The Commission concludes that the RCMP has adequately implemented Recommendation 4. The Commission further concludes that the amended RCMP national policy regarding internal searches is clear, sufficient, and consistent with relevant jurisprudence.

Sections 5.1. through 5.4. of the national personal search policy guides cell block searches. Section 5.1. instructs members to "[r]emove all strings or cords from sweat pants, shorts, hooded sweat tops, or similar clothing that a detainee will be wearing in a cell."

In the Commission's opinion, the wording of this section is clear. Still, it appears that some members have adopted a practice of not only removing strings and cords, but also removing additional clothing.

During the Commission's interviews, 56 of 67 members indicated that, in addition to the removal and seizure of all cords from detained persons, the detainees are routinely "brought down to one layer of clothing." Members stated that they tell detainees that they can either remove their hooded sweatshirt or have the hood cut off. The rationale provided by members, without exception, was the need to be able to see the detained person's face at all times when in the cell block.

In the Commission's opinion, absent sufficiently articulated grounds supporting a belief that the detainee will use their hood, or other clothing, to attempt to escape or inflict harm on themselves or others, the practice of routinely stripping detainees down to one layer of clothing is contrary to relevant jurisprudence and not established by policy. Depending on the layer of clothing that detainees are permitted to keep, the practice may fall within the definition of a "strip search" if the detained person's bra or undergarments are exposed or rearranged during the "bringing down" process.Footnote 13

Sections 5.2. and 5.3. refer to the search and removal of bras or similar undergarments.

In its 2017 Final Report, the Commission recommended that the RCMP amend the divisional policy mandating the removal of bras (as it was contrary to common-law principles and un-reasonable to remove a person's bra without reasonable grounds to conduct a strip search). Despite this Recommendation, the RCMP's national policy pertaining to cell block searches continues to direct members to search bras and similar undergarments as a matter of course.

The courts have established that the police practice of removing or ordering the removal of a prisoner's bra (or other undergarment) constitutes a strip search. Furthermore, the courts have established that, when conducted on a routine basis, this practice is unreasonableFootnote 14 and contravenes section 8 of the Charter.

The Commission's interviews and file review reveal that many members are unaware that the removal or inspection of a prisoner's bra constitutes a strip search, and that many members routinely inspect a prisoner's bra, or have it removed during the process of lodging the prisoner in cells. This practice is very concerning and may be attributed to the national policy direction.

The Commission finds that sections 5.2. and 5.3. are inadequate, inappropriate, and inconsistent with established jurisprudence. Section 5.4. directs members to check detainees with a wand when feasible, before placing them in cells. The Commission concludes that this section provides members with clear and adequate direction.

Finding No. 1: RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" remains inadequate. In particular:

- section 3.1.2.2.1., in reference to the removal of undergarments, is unclear;

- section 3.1.2.4., regarding investigative purposes, is unclear;

- section 5.1., as it relates to the removal of items prior to detainees being lodged in cells, is unclear; and

- sections 5.2. and 5.3., regarding the search and removal of a prisoner's bra, are inadequate, inappropriate, and inconsistent with established jurisprudence.

The national policy does not contain provisions with respect to tracking and assessing compliance with personal search policies. As such, implementation of Recommendation 9 of the Commission's Final Report is inadequate.

Recommendation No. 1:

That the RCMP amend National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search" to ensure adequacy, appropriateness, clarity, and consistency with established jurisprudence.

Divisional Personal Search Policies

The Commission examined the degree to which RCMP divisional personal search policies are adequate, appropriate, sufficient, and clear. With respect to the RCMP's British Columbia divisional policy, the Commission also reviewed the extent to which the RCMP has implemented Recommendations 6 and 9 of the Final Report.

The Commission's conclusions are based on its review of relevant RCMP divisional policies, as well as information obtained during its file review and member interviews conducted from June 2018 through January 2019. In reaching its conclusions, the Commission considered relevant settled case law, including Golden.

The Commission requested all relevant divisional policies from the RCMP. However, the Commission learned that most RCMP divisions do not have divisional personal search policies.

Therefore, divisions rely on the RCMP's national personal search policies for guidance and direction regarding personal searches. Four divisions provided the Commission with copies of their divisional policy relating to personal searches: British Columbia ("E"), Saskatchewan ("F"), Northwest Territories ("G"), and Alberta ("K"). The policies are set out in Appendix 3.

British Columbia ("E" Division) Strip Search Policy

"E" Division's personal search policies (which include its cell block search policy) are generally consistent with the RCMP's national policy. However, the divisional policy on cell block search diverges from the national policy in that it provides additional useful guidance to members, in alignment with relevant jurisprudence. It includes clarification that the removal of a prisoner's undergarments is not routine and constitutes a strip search.

In its 2017 Final Report, the Commission foundFootnote 15 that "E" Division's policy mandating the removal of bras is contrary to common law and that, absent reasonable grounds to conduct a strip search, the removal of a prisoner's bra is unreasonable. The Commission recommended that the RCMP amend "E" Division's personal search policies to reflect current jurisprudence (Recommendation 6).

The amended divisional policy regarding personal searchesFootnote 16 refers members to RCMP's national strip search policy (OM 21.2.3.1.2.). However, it provides additional guidance with respect to cell block searches, which mitigates the inadequacies in the RCMP's national policy on cell block search. "E" Division's policy provides clear and unambiguous direction to members regarding strip search protocols, as well as the circumstances in which these must be followed when lodging prisoners in cells. The RCMP adequately implemented Recommendation 6.

The Commission further recommended that the RCMP amend its national and "E" Division personal search policies to include provisions with respect to tracking and assessing compliance (Recommendation 9). The amended British Columbia divisional policy does not include provisions with respect to tracking and assessing compliance with personal search policies. As such, Recommendation 9 was not adequately implemented.

Finding No. 2: Although significant improvements have been made to the amended policy, by virtue of

its reliance on RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2., "E" Division's policy related to strip searches is inadequate.

Saskatchewan ("F" Division) Strip Search Policy

For the most part, the Saskatchewan divisional policy mirrors the national policy. However, section 5.3., which allows for the possibility of a second member to be present during a strip search, is inconsistent with section 3.1.2.4. of the national RCMP policy. This section provides that, "[i]f a member is not involved in the search they will not observe in any way, unless required for investigative purposes."Footnote 17

Section 5.3. is also inconsistent with the framework established in paragraph 101 of Golden for conducting strip searches incidental to arrest, which provides that the number of police officers involved in the search should be no more than is reasonably necessary in the circumstances.

Finding No. 3: "F" Division policy section 5.3., directing members to have a second member present during a strip search, is inadequate, inappropriate, and inconsistent with established jurisprudence.

Northwest Territories ("G" Division) Strip Search Policy

In the Northwest Territories, RCMP members rely on chapter 21.2. of the RCMP's national Operational Manual, as well as the supplementary divisional policy.

Section 1.3. of "G" Division's personal search policy allows a prisoner to be searched by a member of the opposite sex. This is inconsistent with the relevant RCMP national policy, which stipulates that "all searches must be conducted by a member of the same gender as the detainee being searched unless an immediate risk of injury or escape exists, or in exigent circumstances."Footnote 18

In addition, sections 1.3. and 1.3.1. are contrary to established jurisprudence, including Golden.

"G" Division strip search policy section 2.2. refers to Golden but is inconsistent with relevant jurisprudence by allowing members to use their discretion on whether the Golden elements are satisfied.Footnote 19

Generally, "G" Division's policy does not supplement the RCMP's national strip search policy with either appropriate or useful guidance.

Finding No. 4: "G" Division policy sections 1.3. and 2.2. provide inappropriate and inadequate direction, and are inconsistent with established jurisprudence

Alberta ("K" Division) Strip Search Policy

"K" Division's strip search policy refers members to the national strip search policy, with additional guidance on cavity searches in the policy's section on personal searches.Footnote 20

Finding No. 5: By virtue of its reliance on RCMP National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2., "K" Division's strip search policy is inadequate, insufficient, and unclear

Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP revise divisional policies subsequent to making the recommended amendments to National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search."

Mandatory RCMP Strip Search Training

The Commission examined whether RCMP national and divisional mandatory training, including the training provided in the Cadet Training Program, is adequate, sufficient, and clear. In reaching its conclusions, the Commission reviewed the RCMP cadet training modules and considered information obtained during the interviews of 67 members from various divisions across Canada.

Cadet Training at Depot Division

In its 2017 Final Report, the Commission raised the issue of inadequate strip search training for cadets at Depot Division. It opined that the Cadet Training Program should include guidance to cadets with respect to the articulation of the grounds required to conduct a strip search, and that the program should provide cadets with opportunities to exercise discretion in determining whether to conduct a strip search.

In Finding 8 of its Final Report, the Commission concluded that, "[b]y limiting training on strip searches to a review of relevant policies, procedures, law and written assignments, the RCMP Cadet Training Program fails to provide adequate training to cadets on what constitutes a strip search."

The corresponding Recommendation 7 called for the RCMP to enhance its basic training at Depot Division to ensure that cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, relevant policies, and procedures for all types of personal searches, including strip searches.

In July 2016, the RCMP Commissioner informed the Commission that he supported the Recommendation to enhance basic training at Depot Division regarding personal searches. However, in March 2018, the Commission made enquiries with Depot Division to determine whether the module of the Cadet Training Program that covers the care and handling of prisoners (Module 6, Applied Police Science) had been amended to include scenarios that require cadets to articulate the legal grounds for conducting strip searches. The Commission learned that the RCMP was in the process of modifying scenario training, but subsequent enquiries revealed that the RCMP has not enhanced the Cadet Training Program.

The Commission reviewed materials pertaining to the Cadet Training Program, including training modules and exercises. The curriculum reviewed covers materials related to personal searches, strip searches, and internal searches. Cadets are introduced to a systematic procedure for searching, with an emphasis on frisks and common locations for concealing items.

The curriculum requires cadets to participate in discussions regarding law and RCMP policy pertaining to the types of searches.

In addition, the curriculum includes role plays on arresting prisoners followed by primary search, secondary search, and the removal of personal effects, as well as the completion of the Prisoner Report (form C-13).

The curriculum requires cadets to participate in discussions concerning the reasons for search and seizure of items from prisoners. However, the training does not include any scenarios where cadets are required to articulate their grounds for a strip search. Therefore, the Commission concludes that the RCMP did not adequately implement Recommendation 7 of the Final Report.

The content of the cadet training modules refers to amended RCMP national policies and is consistent with the relevant jurisprudence. The Commission acknowledges that the training modules are designed to provide basic training and that they emphasize personal search, as this is the type of search that cadets regularly conduct in the course of their duties once posted.

The Commission further acknowledges that amendments to the RCMP's personal search policy in the National Headquarters Operational Manual provide guidance and direction to members regarding strip searches subsequent to their cadet training.

However, the basic training regarding strip searches is currently the only mandatory training that members undergo. Moreover, the adequacy of the guidance and direction that members receive subsequent to that training is dependent on the quality of supervision and direction at the detachment level. Therefore, the Commission concludes that the strip search training provided to cadets at Depot Division is inadequate.

Finding No. 6: Strip search training at Depot Division is inadequate and insufficient, as it has not been enhanced to ensure that RCMP cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, policies, and procedures.

Recommendation No. 3: The Commission reiterates its 2017 Recommendation that Depot Division enhance basic training, including scenario-based training (online or in person), to ensure that cadets are cognizant of the legal requirements, and relevant policies and procedures for all types of personal searches.

National Training

In reaching its conclusions as to whether the RCMP's national training regarding strip searches is adequate, appropriate, sufficient, and clear, the Commission considered information obtained during member interviews, as well as the materials that the RCMP made available to the Commission.

These included two courses: "Search and Seizures without a Warrant"and "Search and Seizures with a Warrant." The courses are available online, through Agora,Footnote 21 and their target audience are regular members. Currently, these courses are not mandatory.

While these two courses provide excellent information regarding search and seizures (as it relates to property search, which can be used as evidence in court), they do not directly address strip searches.

Members interviewed during this review stated that the only formal training they have received with respect to strip searches was at Depot Division, when they were cadets.

Interviews with RCMP members in supervisory positions revealed that they have not received specific training with respect to the RCMP's updated national policy on personal searches. However, some of these members indicated that they take it upon themselves to read relevant case law when time permits.

When questioned on the dissemination of a new policy to members within a detachment, supervisors in every division that was reviewed by the Commission indicated that new policies are referenced during briefings (team meetings).

They further stated that, when members are required to complete a particular course, it is usually online, at their desk, and members must sign off their name in a logbook upon completion to ensure that they have read the new practice/procedure. Supervisors emphasized that the numerous mandatory courses are time-consuming, and that members could otherwise dedicate this time to patrolling the streets.

Some supervisors informed the Commission that, due to the volume of various types of training and updates, they must trust their members to complete the required updates/training.

During interviews with members and supervisors, the Commission also found that ongoing training in relation to strip searches was non‑existent.

Members indicated that their "block training" (refresher training sessions that cover various topics and occur every two years) does not include training relating to strip searches. Based on the information shared and the interviews conducted, the Commission concludes that mandatory RCMP national training pertaining to strip searches does not exist, other than the training provided to cadets at Depot Division.

Finding No. 7: RCMP mandatory national training for members and supervisors in relation to strip searches does not exist.

RCMP Divisional Strip Search Training

In its Interim Report, the Commission concluded in Finding 9 that " . . . relying on member or detachment initiative to request training, rather than mandating ongoing practical training in body searches or any training in strip searches in the [divisions], fails to ensure that members have adequate knowledge and experience in these areas." Based on this Finding, Recommendation 8 of the Final Report called for enhanced training of divisional members.

The Commission examined the degree to which Recommendation 8 in the Final Report was implemented and whether mandatory RCMP divisional strip search training is adequate, appropriate, sufficient, and clear.

The Commission's conclusions are based on information and materials provided by the RCMP, the files reviewed by the Commission, as well as interviews conducted with supervisors and general duty members.Footnote 22

In response to Recommendation 8, the then RCMP Commissioner informed the Commission that a memo would be sent to all divisions notifying of amendments to national policy, and that personal searches was being included in the Operational Skills Maintenance Re-Certification.Footnote 23 In the Commission's view, the 2016 memorandum provided adequate notification of the amended national policy on personal searches to the RCMP divisions. However, the Commission determined that RCMP divisions do not currently provide training with respect to strip search policy or require members to undergo such training.

The members interviewed mentioned that they had not received scenario-based training at the detachment level or during any of their block training. In addition, the Commission learned from general duty members, including those with supervisory duties from six divisions, that there is no formal training for supervisors or cell block sergeants with respect to personal searches and the approval of strip searches.

Moreover, the knowledge is self-taught and supervisors keep abreast of current jurisprudence on a voluntary basis. The Commission learned that some detachments, such as the Surrey and Prince George detachments, maintain cell block manuals to provide members with guidance in their handling of detainees in cells.

Members indicated to the Commission that general duty members are briefed on new policies known to their supervisors during team meetings. However, there is no training available on personal searches (after a cadet leaves Depot).

In addition, 67 interviewed members, including those with supervisory duties, indicated that they learned about personal searches, specifically strip searches, from watching other members, and that they will refer to a supervisor when a strip search is required.

In the Commission's opinion, this is problematic insofar as members may lack adequate and sufficient knowledge of what constitutes a strip search, and thus may not refer to a supervisor in instances where the member's actions are tantamount to a strip search.Footnote 24

This was evidenced in Commission interviews, as several members, including those with supervisory duties, were unaware of RCMP strip search policies and procedures and did not know where these policies were located. Furthermore, during its file review, the Commission noted a significant level of non-compliance with RCMP strip search policies.

Finding No. 8: RCMP divisions do not have mandatory training for members and supervisors in relation to strip searches.

The Commission concludes that RCMP divisions do not require members to undergo mandatory training with respect to strip searches, as the training does not exist. Consequently, the RCMP did not adequately implement Recommendation 8 of the Final Report.

Recommendation No. 4: That the RCMP introduce divisional-level mandatory training to ensure that members are cognizant of the legal requirements, policies, and procedures for strip searches, and that the RCMP include this training in the Operational Skills Maintenance Re‑Certification

Evaluating Policy Compliance

During the public interest investigation into policing in northern British Columbia, the Commission found that deficiencies in reporting practices impeded independent review. These included incomplete documentation and inadequate member articulation in the occurrence records management system used by the RCMP in British Columbia—the Police Records Information Management Environment ("PRIME").

In addition, the RCMP records management system did not provide for the tracking or recording of data pertaining to strip searches that would be necessary for either internal or external review.

In its Final Report, the Commission concluded in Finding 10 that, from an accountability perspective, personal search policies and practices at National Headquarters and in "E" Division are not adequate.

Thus, the Commission recommended that the RCMP amend its national and divisional policies to facilitate independent review (Recommendation 9).

The then RCMP Commissioner supported the Recommendation, indicating that the Prisoner Report (form C-13) was being amended and a new desktop application was being developed to allow the RCMP to record, track, and assess compliance with personal search policies.Footnote 25

The Commission's current review confirmed that the RCMP has amended form C-13Footnote 26 (to include a checkbox for all types of searches) and that it has implemented it nationwide. The form is available on desktop computers for members to access in both PROSFootnote 27 and PRIME.

Unfortunately, the form is only available in electronic format. Given that prisoner reports are not automatically saved on the records management system (and in many instances these forms are placed on the paper file), it is not possible to quickly or systematically identify files involving a strip search. Moreover, PROS and PRIME do not have the capability of tracking and extracting certain data, such as specific types of searches (e.g. strip search).

Therefore, all tracking must be done manually, which can be hindered by improper or insufficient data entry on the file. This inability of RCMP computer systems to track certain data severely hampered the Commission's current review, necessitating a manual review of over 11,000 prisoner reports (form C-13) to identify those that may include a strip search.

In the case of some detachments, including the Surrey RCMP Detachment, the Commission was not able to review the requested prisoner reports, as the files were apparently saved in multiple locations and would have required several months to retrieve and copy.Footnote 28

Appropriate document management, storage capabilities, and practices that facilitate review are crucial to the principles of transparency and accountability. The Commission is of the view that the RCMP's record-keeping methods do not facilitate the review (either internal or external) of personal searches and strip searches.

Without the ability to capture, track, and report on cell block and strip search data, RCMP supervisors and detachment commanders, as well as the Commission, are unable to identify individual problems or systemic issues. In the absence of a requirement in policy to record, track and assess compliance, the RCMP is limited in its ability to ensure that members are appropriately applying personal search policies in practice.Footnote 29

The RCMP should consider developing a system to track strip searches similar to the system implemented for use of force incidents.

The Subject Behaviour/Officer Response (SB/OR) database permits online reporting and storage of relevant information.

The RCMP recognizes the need for capturing the details surrounding use of force by police and is developing a reporting framework that will provide increased liability protection for police officers and law enforcement agencies, provide a standardized method of gathering subject behaviour and officer response (SB/OR) data, and provide a means of reporting SB/OR data for statistical, trend analysis and training purposes. Furthermore, stronger accountability to the public will be realized as incidents of use of force employed and the circumstances surrounding them are recorded.

. . .

The implementation of the SB/OR database will be a direct benefit to Canadians as circumstances surrounding the use of force by police will be documented and open to examination when required. This will result in increased transparency by police to the public.Footnote 30

A similar system for strip searches would further promote transparency and accountability.

Finding No. 9: RCMP national and divisional personal search policies do not address an appropriate means of recording and tracking strip searches, or assessing compliance to facilitate internal or independent review.

The Commission concludes that the RCMP did not adequately implement Recommendation 9 of the Commission's Final Report.

Recommendation No. 5: The Commission reiterates its 2017 Recommendation that the RCMP amend its national and divisional Operational Manual policies on personal searches to enhance transparency and accountability, by ensuring that policies include an appropriate means of recording, tracking, and assessing compliance, thus facilitating internal evaluation and independent review.

Detachment-Level Compliance

| Divison/Detachment | No. of C-13s originally identified | No. of c-13s analyzed | No. of Strip Searches ID | No. of Files to request | Occurrence Reports Received | Total Files/Reports received |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J Division | ||||||

| Oromocto / Bathurst | 141 | 142 | 0 | 29 | 36 | |

| Moncton | 1056 | 875 | 0 | 53 | 49 | |

| total | 1197 | 1017 | 0 | 82 | 85 | |

| F Division | ||||||

| Lloydminster | 770 | 775 | 16 | 131 | 127 | |

| Prince Albert* | 386 | 386 | 3 | 61 | 20 | |

| North Battleford* | 2147 | 2147 | 7 | 167 | 60 | |

| total | 3303 | 3308 | 26 | 359 | 207 | |

| G Division | ||||||

| Yellowknife | 1179 | 1190 | 12 | 151 | 136 | |

| V Division | ||||||

| Iqaluit | 1472 | 1424 | 2 | 162 | 162 | |

| M Division | ||||||

| Whitehorse | 1271 | 1120 | 2 | 23 | 18 | |

| E Division | ||||||

| Surrey | 3600 | 0 | 0 | 105 | 105 | |

| Prince George | 1487 | 1654 | 11 | 128 | 169 | |

| Kamloops | 1637 | 1507 | 38 | 108 | 107 | |

| Burnaby | 824 | 586 | 7 | 31 | 31 | |

| total | 7548 | 3747 | 56 | 372 | 412 | |

| Grand Totals | 11806 | 98 | 1149 | 1020 |

*At least half were missing occurrence report numbers. As a result, requested files were manually tracked received several months later (not included in analysis).

The Commission examined whether, in practice, RCMP members are complying with relevant policies and current jurisprudence. As part of its review, the Commission looked at 11,806 prisoner reports (form C‑13) and 1,020 occurrence reports from 13 detachments,Footnote 31 reviewed members' notebooks, and conducted 67 interviews.

Overall, the Commission found a dearth of adequate articulation, a lack of documented supervisory authorization of strip searches, and significant under-reporting of bra/undergarment removals as strip searches where removal of intimate clothing occurs as a matter of course. The extent of member non‑compliance with RCMP strip search policies and relevant jurisprudence was significant.

The file review revealed that prisoner reports often were not completed properly (boxes were not checked off when strip searches were conducted) and thousands of C-13 forms were missing crucial data, such as the prisoner's date of birth, gender and height, and the occurrence report number, which is used to identify the case in the RCMP police reporting systems.

At times, members included handwritten information in the margins or at the bottom of form C-13, when they should have articulated this information in the occurrence report.Footnote 32

For a large number of files reviewed, the members involved did not create a general occurrence report even when a strip search had clearly been conducted (e.g. strip search activities documented on the correlating form C-13, such as intimate items of clothing removed and/or strip search box checked off).

For these files, only the occurrence summary was available, which was automatically generated by dispatch providing a brief synopsis of the "call."Footnote 33 In interviews, members stated that a general occurrence report is created only when further articulation is required for the incident and supplementary reports are documented on the file. Some members informed the Commission that strip searches are not articulated in detail and that it is sufficient to document the occurrence of a strip search in their notebooks or in occurrence reports by using words such as "searched."

The Commission reviewed 1,020 occurrence reports from 13 detachments in six divisions to assess members' articulation of strip searches and compliance with relevant policies. The majority of the occurrence reports that were reviewed contained either no or limited articulation pertaining to strip searches, even in cases where the strip search box was checked off on the Prisoner Report, and in cases where a prisoner's bra, underwear or all of their clothing had been removed.

In many cases, the documented articulation on the occurrence report of a strip search having occurred was minimal.Footnote 34 The Commission also found many instances where supervisors did not document their authorization.

An examination of corresponding members' notes revealed inadequate or non-existent entries regarding strip searches. In most cases where a strip search occurred and notes were made, little information was documented, such as "searched and lodged in cell."

The lack of articulation is in contravention of the Golden decision and RCMP policies. Moreover, the continued practice in some detachments of removing women's bras subject women to a different standard of grounds for a strip search. On its face, the practice is discriminatory based on gender and does not comply with current relevant jurisprudence.

Iqaluit Detachment:

The Iqaluit RCMP Detachment was particularly noteworthy. The Commission reviewed 162 files/occurrence reports from this detachment, 158 of which included references to the removal of a prisoner's bra and/or underwear. Despite this, only three percent of files documented the search.

Furthermore, supervisory authorization for the search was not documented on any of the 158 files. The five files indicating that a strip search had occurred involved the removal of the person's entire clothes, yet only one of these files indicated that a strip search had occurred. The five files included references to self-harm/suicidal prisoners, or high-risk prisoners. According to member interviews, if a person refused to remove their clothing, the members would cut it off, which did not constitute a strip search, in their view.

Moreover, 14 of the 162 files had documented "all clothing removed," without any other articulation with respect to a strip search, with the exception of the one file previously mentioned. These files included documentation to indicate that they related to the Mental Health Act and highly intoxicated persons or high-risk prisoners. Iqaluit RCMP members commented that some prisoners are extremely problematic and return to cells regularly.

As such, members developed a protocol for repeat detainees. For instance, with one such person, Iqaluit members informed the Commission that they have a "procedure" for dealing with her—they turn on the audio and video recording, strip her of her clothing, and put her in a restraint chair for a stipulated time.

Interviews revealed that most members of the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment, including the Officer in Charge, did not know the definition of "strip search." In addition, some members stated that they had never conducted a strip search, while others remarked that a strip search was the act of stripping a prisoner of all their clothing to search for weapons or contraband.

Members remarked that they would more than likely document this action in their notebooks or occurrence reports, and pointed out that, at the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment, strip searches rarely occur.

Members commented that they did not consider the act of stripping a prisoner of their clothing for safety or self-harm reasons as being a strip search, and consequently would not document such an event.

Moreover, members at the Iqaluit Detachment revealed that bras are removed as a matter of course and that supervisor approval is not sought in these cases, as the removal of bras is not considered a strip search.

The rationale for the bra removal, according to members, is to prevent prisoners from using the bra to hang themselves.

The Commission further learned that all strip searches at the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment are conducted in cells and video-recorded.

Iqaluit RCMP Detachment members indicated that supervisors are not available after core working hours and that during this period, they rely on more senior on-duty members for guidance. Therefore, they would not call their supervisor after core working hours to seek authorization for a strip search. Supervisors, as well as the Iqaluit Detachment Commander, confirmed that there is no supervision after hours, and that they do not review files to identify issues relating to compliance with the strip search policy.

Members further indicated to the Commission that the individuals that are subject to this practice are usually intoxicated. They mentioned that the hospital in Iqaluit will not admit these intoxicated individuals, as they may become violent and harm patients. Members stated that they would likely call a mental health nurse to assess the individual within eight hours after the time of initial detention, as they do not have the authority to detain these individuals any longer.

According to the members interviewed, these individuals are often no longer suicidal once sober and therefore released within the eight hours. When asked if members would document the event, specifically the removal of clothing, the members replied that they would not.

The Commission found significant non‑compliance with the RCMP's personal search policy and relevant jurisprudence at the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment. Members do not have adequate knowledge of the strip search policy and appear to lack guidance from supervisors.

Moreover, members often do not seek supervisory guidance or approval with respect to strip searches outside of the detachment's core hours. Members do not document or properly articulate their grounds for conducting a strip search, and there does not appear to be any supervisory file review for compliance with the RCMP's strip search policy. Although this review focused on the Iqaluit Detachment, the Commission is concerned that this may be reflective of a broader divisional problem.

PUBLIC INTOXICATION:

In conducting the review of strip searches, the Commission became aware that the Iqaluit Detachment applies the unsanctioned, unofficial "8-hour rule" for the detention of persons arrested for public intoxication. This detachment‑wide practice is not consistent with national policy on the release of prisoners (chapter 19.9.) or "V" Division's policy on the release of intoxicated persons.

In the "Policing of Public Intoxication" section of the Commission's Final Report into Policing in Northern British Columbia, the RCMP Commissioner agreed to Recommendation no. 14:

That the RCMP amend National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 19.9. to capture the complete list of exceptions listed under section 497 of the Criminal Code.

Chapter 19.9. of the RCMP's national policy has been amended to include all exceptions listed under section 497 of the Criminal Code. It directs that when a subject is arrested without a warrant, members must release them as soon as practicable unless there is a need to: a) establish the identity of the person, b) secure or preserve evidence of or relating to the offence, c) prevent the continuation or repetition of the offence or the commission of another offence, or d) ensure the safety and security of any victim of or witness to the offence. The emphasis is on the release being "as soon as practicable"—there is no generic eight-hour rule for all.

"V" Division's policy (OM 19.9.3. on the release of intoxicated persons and section 81(4) of the territorial Liquor Act authorize the release of a person detained under section 80(1 of the Act), if the person in custody has recovered sufficient capacity and is unlikely to cause injury to himself or herself or be a danger, nuisance or disturbance to others, or a person capable of taking care of the person in custody undertakes to do so. Pursuant to section 81(3) of the Liquor Act, no person apprehended under section 80(1) of the Act shall be held in custody for more than 24 hours.

Although beyond the scope of this current review, it is important that members of the Iqaluit Detachment are cognizant of the law and policy, and carry out their duties accordingly.

Finding No. 10: The Iqaluit Detachment has significant member non-compliance with the RCMP's personal search policy and the relevant jurisprudence.

Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP, particularly in Nunavut, provide operational guidance to members with respect to the handling of vulnerable persons detained (as it relates, for example, to mental health issues and self-harm), and that it consider providing trauma‑informed training.

Recommendation No. 7: That RCMP divisions provide operational guidance to members regarding strip search policies, proper articulation of the required reasonable grounds, documentation of the manner in which the search took place, and proper documentation of supervisory approval.

Prince George Detachment:

In comparison, the Commission found that members at the Prince George Detachment were aware of and compliant with RCMP search policies. Strip searches were conducted in private and not video-recorded. In addition, supervisors were readily available to provide guidance and authorization to members when necessary, and bras were not removed from prisoners as a matter of course.

However, similar to occurrences in Iqaluit, incidents where prisoners were placed in anti-suicide gowns/smocks were not flagged as strip searches even though they involved the removal of all the prisoner's clothing.

The file review indicated that the required documents were completed properly and thoroughly; clear signs of review by supervisors were present with highlighted and circled areas that required correction from members (both in forms C-13 and occurrence reports), and supervisor sign-off was almost always present. Overall, members in Prince George provided adequate documentation in their occurrence reports and notebooks with respect to strip searches and the rationale/authorization for removal of intimate items of clothing.

Burnaby and Surrey Detachments:

The review also revealed some good practices in "E" Division. In Burnaby and Surrey, the cell block sergeants assume the role of "gatekeeper." Therefore, all prisoners being lodged or searched must go through the Cell Block Sergeant, who possesses good overall knowledge of RCMP personal search policies and provides authorization for conducting strip searches.

The Surrey RCMP Detachment developed a poster of its "Strip Search Policy Advisory," which is posted on the wall in the cell block booking area.Footnote 35 The advisory is consistent with the framework outlined in Golden and serves as a useful reference for members.Footnote 36

Surrey Detachment Strip Search Policy Advisory

In addition, the Surrey RCMP Detachment developed a "Cellblock Standard Operating Procedures" manual, as well as a "Cell Block Sergeant Reference/Training Guide" in October 2018 for local detachment use, which is available in and outside the cell block area.Footnote 37

The content of these manuals is derived from the national policy and "E" Division's policy, with a heavy emphasis on the Golden decision.Footnote 38 The Commission also learned that the practice at the Surrey Detachment is to video-record all strip searches. This practice is inconsistent with section 3.1.2.3. of the RCMP's national strip search policy.Footnote 39

Subsequent to the Commission's 2017 Final Report, the Prince George RCMP Detachment developed a manual to help members better understand and comply with its policies and the jurisprudence.

An Operational Manual entitled "PRISONERS: Guarding Prisoners/Personal Effects"Footnote 40 was developed and is kept in the cell block for all members of the detachment to follow in conjunction with the form "Prisoner Report – Personal Searches (Strip Searches)," which is used as a guide so that members know what information to document when they conduct a strip search.

Recommendation No. 9: That the RCMP consider the Prince George RCMP Detachment's cell block Operational Manual ("PRISONERS: Guarding Prisoners/Personal Effects") and Prisoner Report form ("Prisoner Report – Personal Searches [Strip Searches]") as good practice for relevant detachments Force-wide.

Recommendation No. 10: That the RCMP consider providing relevant detachments with copies of the "Strip Search Policy Advisory" poster utilized at the Surrey RCMP Detachment.

Mental Health Act and Vulnerable Prisoners

The Commission's file review and member interviews revealed that, with the exception of the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment, most members of the reviewed detachments deal with searches of persons apprehended for mental health reasons, or persons with a potential of self-harm, on a case-by-case basis. The removal of prisoners' clothing is dependent on their behaviour while in cells. This also applies to the use of anti‑suicide gowns/smocks.

Again, with the exception of members of the Iqaluit RCMP Detachment, members interviewed indicated that documentation would be made in their notebook or occurrence report if a prisoner who indicated self-harm had to be stripped of their clothing and given an anti‑suicide gown/smock.

However, the majority of members interviewed do not view the act of stripping a prisoner of their clothing for self-harm reasons as a strip search, because they are not searching for items such as weapons or contraband.

During interviews, members stated that lodging prisoners with potential self-harm in cells was usually the last option for members if no other facilities were available. The Commission was informed that local hospitals do not accept mental health patients who are intoxicated, and only a handful of detachments interviewed had access to public health alternatives (such as sobering centres) in their area. Iqaluit does not have public health alternatives for social disorder calls for service or Mental Health Act-related situations.

Supervision

In the file review, the Commission noted varying degrees of supervisory involvement in files related to strip search occurrences. In some detachments, there was clear evidence that the supervisor conducted a thorough and timely review. For example, almost all files from the Prince George RCMP Detachment indicated that supervisors had approved the file or "signed off" on it.

In addition, there were clear signs of review on these files, such as highlighted or circled sections that the member had not properly completed.

Moreover, the reason for the strip search and the required supervisory approval were documented on the Prisoner Report. The six files reviewed from the Burnaby RCMP Detachment had been approved by a supervisor and the prisoner report in each file contained adequate articulation and documentation regarding the reason for the search, the location of the search, and the supervisor's approval.

However, with respect to most detachments, that was not the case, contrary to policy. The files reviewed from the Kamloops RCMP Detachment did not contain adequate articulation of the grounds for the strip search. There was no indication of a supervisor's approval in the 86 occurrence reports that related to detainees whose bra or underwear had been removed. In addition, 38 files submitted for review were flagged to indicate that a strip search had been conducted, but only two of these files included articulation of the supervisor's approval.

During interviews with members in supervisory positions, the Commission learned that cases involving strip searches are seldom reviewed in a timely manner, if at all. Supervisors indicated that prisoner reports are occasionally reviewed daily and sometimes reviewed in batches on a monthly basis, at random times, or not at all.

Some supervisors stated that they review occurrence reports to ensure that they contain adequate documentation when the file is nearing closure. However, they mentioned that unless there is some indication on an occurrence report that a strip search was conducted, a supervisor would not know whether the search had taken place according to policy.

With respect to the review of members' notes, supervisors stated that these are usually reviewed to ensure that members are actually making notebook entries and not for the purpose of ensuring policy compliance.

Through interviews with supervisors, the Commission learned that reviews of notes, occurrence reports and prisoner reports for a particular file are not always done by the same supervisor. Moreover, entire files are seldom reviewed in a timely manner unless it relates to a case that will be going to court.

The occurrence reports reviewed by the Commission rarely included documentation indicating that either supervision was provided on the file or that a supervisor had authorized the strip search. During interviews with supervisors, it was found that they could not review the manner in which strip searches were conducted, as the majority of members did not articulate the details in their reports.

Oftentimes, members would document "prisoner was searched or searched and lodged in cells" in their reports or notes.Footnote 41 Furthermore, most supervisors stated that they did not conduct any follow-up with members who had not adequately documented the supervisor's authorization on strip search files.

Most members in supervisory positions do not receive mandatory training regarding the RCMP's strip search policy. The Commission's review demonstrates the correlation between adequate supervisory involvement in a file and adequate member compliance with the RCMP's strip search policy.

At some detachments, it is evident that supervisors are either not concerned with policy compliance or are not providing adequate supervision. It is critical for supervisors to ensure that members properly articulate their grounds for conducting a strip search, as well as other relevant information. Based on the information reviewed, the Commission concludes that, generally, the supervision of members conducting strip searches is inadequate.

Finding No. 11: The overall supervision of members conducting strip searches, and the subsequent supervisory file review for policy compliance, were inadequate in most of the detachments examined by the Commission.

Recommendation No. 8: That the RCMP develop specific supervisor training regarding duties and responsibilities in accordance with National Headquarters Operational Manual chapter 21.2. "Personal Search."

Other Notable Issues

Use of Closed Circuit Video Equipment:

In its 2017 Final Report, the Commission indicated that none of the RCMP's national policies on either personal searches or the use of closed-circuit video equipment provided guidelines, direction, or limitations with respect to recording or capturing searches on camera.

The Commission further indicated that, in light of R v Fine, the RCMP should amend its policies and practices to ensure that the use of such equipment during strip searches does not infringe on the Charter rights of the person being searched. In response, the RCMP amended its strip search policy. Section 3.1.2.3. of the RCMP's national strip search policy now provides the following direction:

If a private room is not available for the search, conduct the search in a cell and ensure the monitor is turned off or covered to ensure all measures are taken to provide privacy to the detainee.

In the Commission's opinion, the amended policy is adequate and clear.

The Commission's review revealed that, in practice, some detachments follow the amended policy and conduct strip searches in a private room that is not being video‑recorded, while others have their own procedure with respect to the video‑recording of strip searches.

For example, the Surrey RCMP Detachment has a strip search room where strip searches are video-recorded. The Commission was informed that the video is not live-monitored and only the supervisor can view the recording if and when required (e.g. further to a complaint, request from the Crown, or cell block incident).

Members from five of the detachments reviewed (Iqaluit, Surrey, Kamloops, North Battleford, and Prince Albert RCMP detachments) informed the Commission that they record strip searches to protect themselves from false allegations.

Of note, in the Burnaby Detachment, members use a digital mask feature to record strip searches, in a dedicated cell. When conducting a strip search, the person being searched stands behind a line in the cell and the camera's digital mask filters them out of the video footage.

Consequently, only members conducting the strip searches are visible in the video recording, which is retained for the standard two years, according to the RCMP's retention policy.

This is an effective way to ensure member compliance without violating the individual's rights. According to information provided by members of the detachment, the digital mask is a feature of their camera and the room size is not a factor, as the mask can be resized to fit the room.

To audit compliance with policies and procedures, the RCMP may wish to consider the use of cameras equipped with digital masks to record members conducting strip searches on prisoners.

Recommendation No. 11: That the RCMP provide clearer direction to divisions regarding the use of closed‑circuit video equipment during strip searches in order that members do not infringe on the Charter rights of the person being searched.

Internal and Cross Gender Searches:

During interviews with members across all divisions, the Commission found that members were all aware of the policies and procedures surrounding internal searches as well cross-gender searches, including the requirement pertaining to exigent circumstances.

RCMP Implementation of the 2017 Final Report Recommendations

As part of this review, the Commission assessed the degree to which the RCMP implemented the relevant RecommendationsFootnote 42 supported by the Commissioner.

The implementation of Recommendation 1 is adequate.

The amended national policy definitions for "personal search" (previously referred to as "body search") and "strip search" are consistent with current jurisprudence, providing a clear distinction between a personal search (i.e. frisk) and a strip search.

The implementation of Recommendation 2 is adequate.

The RCMP amended chapter 21.2. of its national policy regarding personal searches, and now ensures a more robust supervisory oversight by explicitly requiring a supervisor's approval prior to conducting a strip search unless exigent circumstances exist. The amendment in policy provides clear guidance.

The implementation of Recommendation 3 is adequate.

The RCMP amended chapter 21.2. of its national policy regarding personal searches to clarify if, and when, a strip search of a person of the opposite sex is ever permitted. The amended policy articulates the circumstances or criteria that must be met prior to conducting or overseeing a strip search of a person of the opposite sex (i.e. if immediate risk of injury or escape exists and/or in exigent circumstances).

The implementation of Recommendation 4 is adequate.

The RCMP amended its internal search policy and ensures that it clearly specifies the necessary grounds required prior to conducting an internal search as well as the required approvals.

The implementation of Recommendation 5 is adequate.