Public Interest Investigation Into the Events and the Actions of the RCMP Members Involved in the National Energy Board Hearings in British Columbia

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act

Subsection 45.76(1)

Complainant: British Columbia Civil Liberties Association

Table of Contents

Complaint and Public Interest Investigation

Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

- Northern Gateway Project

- National Energy Board

- National Energy Board Mandate

- National Energy Board Hearings

- National Energy Board Role with Respect to Security and Intelligence

- Interaction between the RCMP and the National Energy Board

- Comment on the National Energy Board's Intelligence-Gathering Activities

- RCMP

- RCMP Mandate and Intelligence-Led Policing

- RCMP Integration and Information Sharing

- Joint Working Group – Resource Development

- Intelligence and Public Order Policing

- Public Hearing Process and Factual Background

- Threat Level

- RCMP Presence at the National Energy Board Hearings

- Monitoring of a Protest at the Prince Rupert Courthouse

- Monitoring of Protests by the Critical Infrastructure Intelligence Team

- Monitoring by Unidentified Members of Various Persons and Groups seeking to Participate in the National Energy Board Hearings

Third Allegation: The RCMP improperly disclosed information concerning various persons and groups

- Sharing Information with Natural Resources Canada

- Sharing Information with the National Energy Board

The Alleged "Chilling Effect" of the RCMP's Activities

Appendix A – Complaint of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, dated February 6, 2014

Appendix B – Public Interest Investigation, dated February 20, 2014

Related Links

- CRCC Final Report

December 11, 2020 - RCMP Commissioner's Response

November 20, 2020

Introduction

[1] In 2012 and 2013, the National Energy Board ("NEB") conducted a series of public hearings as part of the assessment process for the planned Northern Gateway Project, an oil pipeline that would run from the Alberta oil sands to a port in British Columbia. The pipeline and related issues inspired significant controversy, particularly among Aboriginal and environmental conservation groups. Vocal opposition and protest, including the rise of the Idle No More movement, broke out across Canada in response.

[2] In British Columbia, where many of the NEB hearings took place, some of the hearings were met with protests. These protests were generally peaceful, but some disruptive incidents were a cause of concern for the NEB. As the police force of jurisdiction in much of British Columbia, as well as possessing national security and critical infrastructure protection mandates, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police ("RCMP") was called upon to assist with event security as well as to assess potential criminal threats. This meant that RCMP members were often physically present at hearings and protests, and also meant that the RCMP engaged in intelligence-gathering activities regarding upcoming protests and demonstrations in order to identify potential criminal activity.

[3] The British Columbia Civil Liberties Association ("BCCLA") has raised a number of concerns about the activities of the RCMP in relation to protests, demonstrations, and other lawful forms of dissent surrounding the pipeline hearings. These allegations call into question the RCMP's ability to fulfil its law enforcement and national security obligations while respecting lawful dissent. This report serves to provide a thorough review of the RCMP's conduct with respect to the allegations.

Complaint and Public Interest Investigation

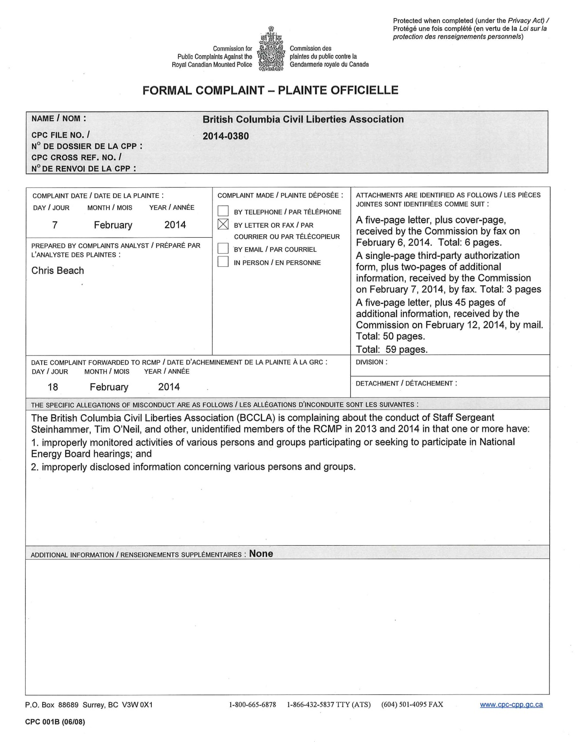

[4] The Commission received the complaint from the BCCLA on February 6, 2014 (Appendix A). The BCCLA stated in its complaint that, based upon documents provided pursuant to an Access to Information Act request, members of the RCMP:

- Improperly monitored activities of various persons and groups seeking participation in NEB hearings;

- Improperly engaged in covert intelligence gathering and/or infiltration of peaceful organizations; and

- Improperly disclosed information concerning persons and groups.

[5] On February 20, 2014, the Commission notified the Minister of Public Safety and the RCMP Commissioner that it would conduct a public interest investigation into the BCCLA's complaint (Appendix B), pursuant to the authority granted to it under subsection 45.43(1) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act ("RCMP Act") (now subsection 45.66(1)).

[6] On February 20, 2014, the Commission also notified the BCCLA that it would conduct a public interest investigation in response to its complaint.

[7] Pursuant to subsection 45.76(1) of the RCMP Act, the Commission is required to prepare a written report setting out its findings and recommendations with respect to the complaint. This report will examine the events and the actions of the RCMP members involved in the NEB hearings in British Columbia. The Commission's role is to examine the conduct of RCMP members in the execution of their duties against applicable training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements and, where applicable, make remedial recommendations. This report constitutes the Commission's investigation into the issues raised in the complaint, and the associated findings and recommendations. A summary of the Commission's findings and recommendations can be found in Appendix C.

Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

[8] It is important to note that the Commission is an agency of the federal government, distinct and independent from the RCMP. When conducting a public interest investigation, the Commission does not act as an advocate either for the complainant or for RCMP members. The Commission's role is to reach conclusions after an objective examination of the evidence and, where judged appropriate, to make recommendations that focus on steps that the RCMP can take to improve or correct conduct by RCMP members.

[9] The Commission's findings, as detailed below, are based on a thorough examination of the extensive investigation materials, and the applicable law and RCMP policy. It is important to note that the findings and recommendations made by the Commission are not criminal in nature, nor are they intended to convey any aspect of criminal culpability. A public complaint is part of the quasi-judicial process, which weighs evidence on a balance of probabilities. Although some terms used in this report may concurrently be used in the criminal context, such language is not intended to include any of the requirements of the criminal law with respect to guilt, innocence or the standard of proof.

[10] The Commission has also relied in large part on the independent investigation conducted by the Commission's investigator, which included a review of several thousand pages of documents provided by the RCMP at the national and divisional (provincial) level as well as discussions with RCMP officials. The Commission wishes to acknowledge that the RCMP's "E" Division (British Columbia) provided complete cooperation to the Commission throughout the public interest investigation process.

Northern Gateway Project

[11] Canada has the third-largest reserve of oil in the world.Footnote 1 According to Natural Resources Canada, the "[t]otal Canadian proven oil reserves are estimated at 171.0 billion barrels, of which 166.3 billion barrels are found in Alberta's oil sands and an additional 4.7 billion barrels in conventional, offshore and tight oil formations."Footnote 2 While being host to most of Canada's oil reserves, Alberta is landlocked. This presents significant challenges with respect to transporting oil both within Canada as well as to markets in the United States of America and overseas. Historically, oil pipelines have played a critical role in such transport.

[12] The Northern Gateway Project consists of a twin pipeline expected to ". . . run 1,177 km from Bruderheim, Alberta, across northern British Columbia, to the deep-water port of Kitimat."Footnote 3 One of the primary purposes of the Project would be to provide access to Canadian oil to international markets, including Asia and the United States West Coast.Footnote 4

Image source: NorthernGateway.ca

[13] The route would cross private land in about half of the Alberta portion and over 90 percent of the route in British Columbia would be on provincial Crown lands, while "[m]uch of the route in both provinces would cross lands currently and traditionally used by Aboriginal groups."Footnote 5 In addition to the pipeline, the Project would ". . . require a terminal to be built and operated at Kitimat including two tanker berths, three condensate storage tanks, and 16 oil storage tanks."Footnote 6

[14] The Project would cost approximately $7.9 billion to build with a projected completion date of late 2018.Footnote 7 It would result in Kitimat becoming a much busier place, with 190–250 oil tanker calls per year.Footnote 8 The Project could operate for 50 years or more.

[15] As part of the approval process, the Project was subject to an assessment by a Joint Review Panel that had been established in 2009 by the NEB and the Minister of the Environment pursuant to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and the National Energy Board Act.Footnote 9 The direction given to the Panel was to "conduct an environmental assessment of the project and submit a report recommending whether or not the project was in the public interest."Footnote 10 The Panel consisted of two members of the NEB, and a third temporarily appointed one.Footnote 11

[16] Defined as an expert tribunal, the Joint Review Panel was ". . . required to determine the sufficiency of the application, hold public hearings, and conduct a technical analysis of the project based on all of the evidence, ultimately making a recommendation on whether the project should be approved or not."Footnote 12 The Joint Review Panel would report its findings and recommendations to the Governor in Council for its consideration on whether to approve the Project.

[17] On December 19, 2013, the Project received the Joint Review Panel's approval subject to 209 conditions (including conditions requiring affected Aboriginal groups to have input into the planning, construction and operation of the Project, environmental and monitoring commitments, emergency preparedness and response matters, and the delivery of economic benefits). The federal government approved the Project on June 17, 2014, when the Governor in Council directed the NEB to issue Certificates of Public Convenience and Necessity for the Northern Gateway Project. Throughout the approval process, the Project has been the subject of considerable media and public attention.Footnote 13

[18] In June 2016, the Federal Court of Appeal quashed the approval of the Northern Gateway Project on the basis that the federal government had failed to properly consult First Nations affected by the pipeline.Footnote 14 This followed a request for judicial review of the Project's approval that was brought by a number of British Columbia Aboriginal groups. The federal government later decided not to appeal this decision,Footnote 15 and on November 29, 2016, announced that it would not approve the Northern Gateway Project.Footnote 16

National Energy Board

a. National Energy Board Mandate

[19] The NEB is the independent energy and safety regulator of Canada. It was established in 1959, following the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Energy,Footnote 17 with the mandate to "promote safety and security, environmental protection and economic efficiency in the Canadian public interest, in the regulation of pipelines, energy development and trade."Footnote 18

[20] The main responsibilities of the NEB are established in the National Energy Board Act ("NEB Act"), and include regulating the complete life cycle of any pipeline projects that cross international borders or provincial boundaries. Before a pipeline can be built, the proponent must file an application with the NEB and the NEB must assess the pipeline's proposed design, construction and operation for safety and for adequate environmental protection, and must ensure that the project is in the public interest.Footnote 19

b. National Energy Board Hearings

[21] In its Annual Report, the NEB states that it ". . . listens to what Canadians have to say about how energy infrastructure is developed and regulated, engaging them in meaningful dialogue about issues and solutions, and publically sharing information about regulatory initiatives."Footnote 20

[22] The NEB conducts public hearings as part of the assessment process for major energy projects, including international or interprovincial pipelines like the Northern Gateway Project. Public hearings give ". . . participants . . . an opportunity to express their point of view, and possibly ask or answer questions about a proposed project or application. This provides the NEB with the information it needs to make a transparent, fair and objective recommendation or decision on whether or not a project should be allowed to proceed or an application should be approved."Footnote 21 During hearings, the topics discussed typically include the design and safety of the project, environmental matters, the impact of a project on directly affected Aboriginal groups, socio-economic and land matters, the economic feasibility of the project, and the Canadian public interest.Footnote 22

[23] The NEB website contains information about upcoming hearings, how to participate in a hearing's process,Footnote 23 as well as its Participant Funding Program. The NEB has an active presence on social media, including Twitter (@NEBCanada), where under the hash tag #NEBhearing it provides content, links to material and live updates of presentations and topics being discussed in public hearings. For those who cannot attend the hearings in person, the NEB hearings can even be listened to live online on the NEB website.

c. National Energy Board Role with Respect to Security and Intelligence

[24] The NEB is part of the portfolio of Natural Resources Canada, the mandate of which includes the protection of critical infrastructure under federal jurisdiction. The RCMP and Natural Resources Canada are jointly responsible for the security of Canada's critical infrastructure, with Natural Resources Canada specifically responsible for energy infrastructure, such as energy transmission lines and oil and gas pipelines. Canada defines "critical infrastructure" as "processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well‑being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government."Footnote 24 Disruptions to critical infrastructure "could result in catastrophic loss of life, adverse economic effects and significant harm to public confidence."Footnote 25 The vulnerability of critical infrastructure to attacks such as sabotage and terrorism is well understood, as these systems are typically large and decentralized and difficult to protect.Footnote 26

[25] The Public Safety Act, 2002, which was enacted by Parliament in 2004, amended the NEB Act "by extending the powers and duties of the National Energy Board to include matters relating to the security of pipelines and international power lines."Footnote 27

[26] The NEB is reported to ". . . operate with a high degree of autonomy, including in [its] interaction with elements of the Canadian security and intelligence community."Footnote 28 In relation to this infrastructure protection role, the RCMP and Natural Resources Canada share information and intelligence.Footnote 29 In addition to its interaction with law enforcement, the NEB also shares information with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service ("CSIS"), and the Integrated Threat Assessment CentreFootnote 30 ("ITAC") may consult with Natural Resources Canada with respect to "subject matter within its expertise, or during the preparation of an ITAC threat assessment."Footnote 31

[27] In the context of the public hearing process, one of the set NEB goals is to hear from those directly affected by a project in a safe and respectful environment. The NEB considers the safety of hearing participants and the general public who attend hearings to be a first priority. The Canada Labour Code guides the NEB in ensuring that all requirements are met for a safe public hearing.Footnote 32

[28] According to its Annual Report, the NEB ". . . conduct[s] a security assessment on a hearing location prior to any hearing, and would look at things such as publicly available information to assess any prior planned events that may have an impact on a venue. [The NEB] work[s] with local officials and federal colleagues such as the RCMP to conduct the assessment."Footnote 33 The security assessment is then used to ensure that plans are in place to provide for security officers, emergency evacuation plans, and other plans aimed to protect everyone in participation.

d. Interaction between the RCMP and the National Energy Board

[29] As noted above, the RCMP and Natural Resources Canada share information and intelligence in following their critical infrastructure security mandates, and the NEB works with local and federal officials (including the RCMP) in the conduct of security assessments related to the public hearing venues.Footnote 34

[30] Organized under the RCMP's National Security Criminal Investigations Program, the RCMP Critical Infrastructure Intelligence Team ("CIIT") focuses on the Government of Canada's critical infrastructure protection mandates. In doing so, it produces ". . . threat and risk assessments, indications and warnings, and intelligence assessments relevant to critical infrastructure, as well as provid[es] support for investigations related to threats to critical infrastructure."Footnote 35 Its threat assessments are specific to criminal threats and "do not infringe on legal, non-violent, protest and dissent."

[31] According to the RCMP's website, the CIIT "collaborates closely with domestic partners at the federal and provincial government levels, as well as other law enforcement groups and private sector stakeholders. As part of its mandate, it has developed the Suspicious Incident Reporting ("SIR") system to gather information from industry and law enforcement about suspicious incidents that may have a nexus to national security."Footnote 36

[32] The NEB and the RCMP have entered into an agreement for the NEB to have access to SIR. The preamble to the agreement emphasizes that information sharing and information protection among critical infrastructure stakeholders and the Government of Canada and its security partners (including the RCMP) is an important element of critical infrastructure protection. Under the terms of the agreement, the NEB is expected to report suspicious incidents that could indicate a possible criminal threat to Canada's critical infrastructure. For its part, the RCMP provides the NEB with assessments about potential criminal threats to critical infrastructure based on reports to SIR and other information sources.

[33] In terms of protecting against the disclosure of personal information, it should be noted that there is no intention under the arrangement to collect personal information, and the NEB must take all reasonable measures to preserve the confidentiality of information obtained through the system against accidental or unauthorized access, use or disclosure. The NEB must treat information obtained through the system in accordance with its security markings, and must respect all caveats, conditions and terms attached to the information obtained from the system. The NEB is also prohibited from sharing SIR information with any third party without prior written consent from the RCMP.

[34] Information sharing between the RCMP and the NEB in the context of the NEB hearings is the subject of the present report.

e. Comment on the National Energy Board's Intelligence-Gathering Activities

[35] In its public complaint, the BCCLA first points to ". . . recent media reports indicat[ing] that the National Energy Board . . . has engaged in systematic information and intelligence gathering about organizations seeking to participate in the Board's Northern Gateway Project hearings."Footnote 37

[36] Relying on records obtained under the Access to Information Act, the BCCLA adds that "this information and intelligence gathering was undertaken with the cooperation and involvement of the RCMP and other law enforcement agencies, and that the RCMP participates in sharing intelligence information with the Board's security personnel, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service . . . and private petroleum industry security firms."Footnote 38

[37] On the basis of these records, the BCCLA advances that ". . . the targeted organizations are viewed as potential security risks simply because they advocate for the protection of the environment."Footnote 39

[38] The Commission does not have jurisdiction to review the actions of the NEB; however, as previously noted, the NEB Act, the Public Safety Act, as well as the NEB mandate and its Annual Report, all make it clear that the NEB has an information- and intelligence-sharing mandate with the RCMP as well as intelligence agencies. This has been recognized by a previous judicial inquiry.Footnote 40 In this context, the Commission will review the activities of the RCMP members as they relate to those who would have participated in or commanded the activities complained about in the BCCLA letter pertaining to the monitoring and disclosure of information in relation to the NEB hearings.

RCMP

a. RCMP Mandate and Intelligence-Led Policing

[39] At common law, police duties (including those of the RCMP) include the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime, and the protection of life and property.Footnote 41 Section 18 of the RCMP Act establishes statutory duties for RCMP members, which include among other things the enforcement of laws, the execution of warrants, crime prevention, and keeping the peace.Footnote 42 The RCMP website describes its broad mandate as including:

. . . preventing and investigating crime; maintaining peace and order; enforcing laws; contributing to national security; ensuring the safety of state officials, visiting dignitaries and foreign missions; and providing vital operational support services to other police and law enforcement agencies within Canada and abroad.Footnote 43

[40] By virtue of subsection 6(1) of the Security Offences Act, the RCMP is the primary agency responsible for national security law enforcement.Footnote 44 This includes preventing and investigating offences arising from conduct constituting a threat to the security of Canada. Such threats are defined in the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act ["the CSIS Act"], which refers to:

(a) espionage or sabotage that is against Canada or is detrimental to the interests of Canada or activities directed toward or in support of such espionage or sabotage,

(b) foreign influenced activities within or relating to Canada that are detrimental to the interests of Canada and are clandestine or deceptive or involve a threat to any person,

(c) activities within or relating to Canada directed toward or in support of the threat or use of acts of serious violence against persons or property for the purpose of achieving a political, religious or ideological objective within Canada or a foreign state, and

(d) activities directed toward undermining by covert unlawful acts, or directed toward or intended ultimately to lead to the destruction or overthrow by violence of, the constitutionally established system of government in Canada . . . .Footnote 45

[41] Of note, the definition of "threats to the security of Canada" expressly does not include lawful advocacy, protest or dissent, unless carried on in conjunction with one of the above acts.

[42] The RCMP has a wide range of national security-related mandates and responsibilities, including the protection of critical infrastructure.Footnote 46 These national security activities, including national security criminal investigations conducted by National Security Investigation Sections and Integrated National Security Enforcement Teams and RCMP provincial divisions, are organized under the RCMP's National Security Program overseen by the Assistant Commissioner, National Security Criminal Investigations. The RCMP's activities in support of its national security mandate include:

collecting, maintaining and analyzing information and intelligence related to national security; sharing such information and intelligence with other agencies, both domestic and foreign; preparing analyses and threat assessments and developing other methods of support for internal and external purposes; investigating crimes related to national security; investigating and countering activities to prevent the commission of crimes related to national security; and protecting specific national security targets.Footnote 47

[43] In pursuing its national security activities, the RCMP engages in what is known as intelligence-led policing. This model of policing recognizes that there is an overlap between the use of intelligence and the traditional policing law enforcement function when it comes to detecting and preventing crime.Footnote 48 It involves the collection and analysis of informationFootnote 49 to produce intelligence that informs police decision-making and operations, and is employed by most major police forces in the Western world. The intelligence produced by the RCMP is referred to as "criminal intelligence," as distinct from the security intelligence collected by CSIS.Footnote 50 It is characterized as intelligence with a link to criminal activity, gathered in support of investigations with the goal of "preventing or deterring a criminal act or of arresting a criminal."Footnote 51 According to the RCMP website for the Criminal Intelligence Program, criminal intelligence:

. . . enables the organization to "connect the dots", in order to increase public safety, i.e. follow manifestations of unlawful activity from ‘local to global' to prevent crime and to investigate criminal activity. Intelligence-led policing requires reliance on intelligence before decisions are taken, be they tactical or strategic.

. . .

Information collected in the context of lawful investigations by the RCMP is collated with information from many other sources. It becomes intelligence when it is analyzed in the Criminal Intelligence Program (CIP) by professional criminal intelligence analysts to ascertain validity and ensure accuracy before it is included in a threat assessment.Footnote 52

b. RCMP Integration and Information Sharing

[44] The RCMP shares national security information and intelligence with its partner agencies inside and outside of Canada.Footnote 53 The RCMP is bound by agreements (such as its Memorandum of Understanding with CSIS) and, in some instances, legislation, requiring the RCMP to share information with others. The RCMP Operational Manual provides some guidance as to information sharing. Of relevance to this report, RCMP policy cautions that disclosure of personal information must be made in accordance with the Privacy ActFootnote 54 (which defines "personal information" as "information about an identifiable individual that is recorded in any form"),Footnote 55 and must be based on a "need to know" and a "right to know" the information.

[45] The Privacy Act generally prohibits the disclosure of personal information without the consent of the individual to whom the information relates, subject to certain exceptions. One such exception is "consistent use disclosure," which means that where personal information has been collected for one purpose (such as law enforcement), it may be disclosed for a purpose consistent with that purpose.Footnote 56 Another exception is "public interest disclosure," which means that personal information may be disclosed if the public interest in its disclosure "clearly outweighs any invasion of privacy that could result from the disclosure . . . ."Footnote 57 A further exception involves disclosure of personal information to certain designated investigative bodies in Canada, following a written request from that body, for the purpose of enforcing any law of Canada or a province or for carrying out a lawful investigation.Footnote 58

[46] When sharing classified or national security information with other Canadian departments and agencies, the RCMP requires that a caveat be added stating:

This document is the property of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), National Security Program. It is loaned specifically to your department/agency in confidence and for internal use only, and it is not to be reclassified, copied, reproduced, used or further disseminated, in whole or in part, without the consent of the originator. It is not to be used in affidavits, court proceedings, subpoenas or any other legal or judicial purpose without the consent of the originator. The handling and storing of this document must comply with handling and storage guidelines established by the Government of Canada for classified information. If your department/agency cannot apply these guidelines, please read and destroy this document. This caveat is an integral part of this document and must accompany any extracted information. For any enquiries concerning the information or the caveat, please contact the OIC [Officer in Charge] National Security Criminal Operations, RCMP.Footnote 59

In this way, the RCMP aims to maintain control over the information it shares with its partners.

[47] Integration and interaction with other police forces and government agencies has become an integral part of the RCMP's national security activities.Footnote 60 During his testimony before the Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar, former Commission Chairperson Paul Kennedy identified globalization, the Internet and encrypted communications, new criminal partnerships, and emerging threats such as new forms of terrorism, as driving this need:

[M]odern policing reality is that some of these challenges can't be addressed by individual police forces acting alone. That is just the reality. There is an obvious need for police to combine resources, both human and financial, and to maximize unique skillsets.

. . .

To address these challenges police forces have integrated their operations and they have adopted intelligence-led policing models which engage multiple partners at the municipal, provincial, federal and international level. This is the new norm.

. . .

This inter-agency co-operation finds expressions at all levels of the public safety framework. In other words, it isn't just police doing this.Footnote 61 [Emphasis added]

[48] The importance of integration is reflected in the RCMP reorganizing some of its National Security Investigation Sections ("NSISs") into Integrated National Security Enforcement Teams ("INSETs"). NSISs and INSETs operate at the divisional level (where most of the investigative work regarding national security matters is carried out),Footnote 62 and have primary responsibility for criminal investigations relating to national security.Footnote 63 NSISs are made up entirely of RCMP personnel. To facilitate greater integration of resources and intelligence among its partners, the RCMP established INSETs, four of which were created from NSISs following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.Footnote 64

[49] INSETs work in ". . . early detection and prevention of any potential threats to Canada and the public."Footnote 65 They are integrated teams comprised of RCMP members and seconded federal partners and agencies, as well as provincial and municipal police services who share their services. Their activities are overseen by the RCMP Headquarters; RCMP policies, rules, and accountability all apply to INSET members. The mandate of the INSETs is threefold: (1) increase the capacity to collect, share and analyse intelligence among partners, with respect to targets (individuals) that are threats to national security; (2) create an enhanced enforcement capacity to bring such targets to justice; and (3) enhance partner agencies' collective ability to combat national security threats and meet specific mandate responsibilities.Footnote 66 While the primary function is investigative with respect to national security, integrated units also perform intelligence analysis, and are not restricted to national security matters.Footnote 67

[50] In British Columbia, where the matters complained of took place, the RCMP provides provincial policing services as well as contract policing services to many municipalities.Footnote 68 To facilitate the flow of information, the province created an integrated information management system that allows the RCMP and municipal police forces like the Vancouver Police Department and the Victoria Police Department to share information. Under the provincial Police Act,Footnote 69 all police agencies, including the RCMP, are required to employ the Police Records Information Management Environment ("PRIME-BC"). This allows real-time sharing of information across municipal boundaries, such that information about an incident in one part of the province can be accessed by police officers in another municipality. These entries may yield intelligence that can assist in matters such as anti-terrorism investigations by revealing information such as the movement of suspects.Footnote 70 PRIME-BC is utilized by 13 independent and provincial police agencies and 135 RCMP detachments in British Columbia.Footnote 71 PRIME‑BC is also accessible to the RCMP's "E" Division headquarters and federal units.Footnote 72

c. Joint Working Group – Resource Development

[51] From the materials provided to the Commission, it appears that, in 2012, the RCMP established a criminal operations joint working group with respect to resource development in British Columbia. Its mission statement acknowledged the "Rights and Freedoms of every Canadian citizen including the right to free speech and the right to lawful protest," and provided that "[t]he public safety of all Canadians and the safety and integrity of Canada's critical infrastructure must be protected."

[52] The membership of the Joint Working Group included multiple RCMP units, such as the CIIT, the "E" Division Criminal Intelligence Section, the "E" Division National Security Program, the "E" Division INSET, "E" Division Aboriginal Policing Services, and the "E" Division North District (which includes Terrace and Prince Rupert). CSIS BC Region was also represented in the group. The "E" Division Southeast District (which includes Kelowna) was added to the working group in October 2012.

[53] Guided by the Canadian Charter of Rights and FreedomsFootnote 73 ("Charter"), the Criminal Code, and other federal and provincial legislation, the mandate of the Joint Working Group was to assess public safety concerns with respect to resource development projects proposed in British Columbia. In particular, the Joint Working Group was to "maintain situational awareness" on resource development proposals, NEB review processes, and decisions by the Government of Canada regarding development proposals in British Columbia, including the Northern Gateway Project. The group would monitor the efforts of operational units responsible for the collection and assessment of open source and confidential source information, "and provide strategic advice to ["E" Division Criminal Operations] on potential threats to public safety."

d. Intelligence and Public Order Policing

[54] Intelligence-led policing is also of particular importance with respect to policing "public order events" such as protests and demonstrations. Although the practice of gathering intelligence in this context is controversial, police must be prepared for any eventuality, and they have been heavily criticized for having failed to obtain sufficient prior information to prepare for acts of public disorder when they take place.Footnote 74

[55] A research paper commissioned by the Ipperwash Inquiry (established to inquire and report on events surrounding the death of Dudley George during a protest by First Nations representatives) noted that obtaining intelligence about planned protests and demonstrations informs police decision-makers, which leads to the development of a strategic plan and tactics. The basic police objective regarding protests and demonstrations is to determine the intention of the organizers. They may then prepare a course of action "for a measured response to maintain public order while respecting individual and collective rights."Footnote 75

[56] The preferred intelligence-led police approach to a public order event is called the "measured response." Its steps are:

- Use intelligence to tell the story of the event as it approaches.

- Prepare a plan that includes all the police abilities, in case they are needed.

- Make every effort to stay low on the continuum of force by interacting with protesters in an open-handed fashion.

- Use police officers in normal uniform, and be with the protesters.

- Only escalate up to the continuum of force when no other choice is available.

- Return to open-handed methods as soon as conditions permit.Footnote 76

Public Hearing Process and Factual Background

[57] In 2012, the NEB Act was amended with the passage of omnibus Bill C-38 (enacted as the Jobs, Growth and Long-term Prosperity Act)Footnote 77 to create a faster, more streamlined assessment process. This had an impact on participatory rights to the hearings and the scope of the NEB's assessment for pipeline projects. Prior to the enactment of Bill C-38, the NEB Act allowed the NEB to accept any "interested person" to participate in the review process.Footnote 78 This term was not defined, affording the NEB considerable discretion in determining who qualified, and this discretion was typically applied liberally. However, Bill C-38 amended the NEB Act such that only persons who were "directly affected" by the proposed project or who had "relevant information or expertise" could participate in the hearings.Footnote 79 This restricted the qualifications for participation to matters concerning the project itself and not wider concerns such as climate change and oil sands. Similarly, the scope of NEB hearings was narrowed to consideration of matters directly related to the pipeline.Footnote 80 It must be noted that these changes did not apply to the Joint Review Panel hearings for the Northern Gateway Project, as the Joint Review Panel process was already underway at the time of the enactment. Nevertheless, the amendments to the NEB Act were seen by some politicians and members of the public as a means of "gutting"Footnote 81 the assessment process and excluding public participation.

[58] As part of the Joint Review Panel's assessment process for the Northern Gateway Project, extensive public hearings were held. A Hearing Order was issued in May 2011 that outlined the joint review process and invited participation, including by the public and by Aboriginal groups, through letters of comment, oral statements, intervenor status, or government participant status.Footnote 82 The review process would include community hearings (where oral statements and oral evidence from intervenors would be heard) and final hearings (where intervenors and government participants ". . . could provide written and oral evidence, request information, question witnesses, and present written and oral final argument.")Footnote 83 Aboriginal groups were encouraged to participate and provide information to help the Joint Review Panel in its deliberations, and the Crown was to provide expert scientific and regulatory advice.Footnote 84 Participants in the hearings included the Gitxaala Nation, the Haisla Nation, the Kitasoo Xai'xais Band Council, the Haida Nation, the ForestEthics Advocacy Association, B.C. Nature, and Unifor, to name a few, as well as a number of departments and agencies.Footnote 85

[59] The Joint Review Panel hearings for the Northern Gateway Project took place between January 2012 and June 2013 in a variety of locations along the planned pipeline route, including Edmonton, Alberta, and the British Columbia towns of Kitamaat Village, Prince Rupert, Terrace, and Prince George. The hearing venues included community centres, hotels, and schools. The Joint Review Panel received letters of comment and oral statements, including statements from representatives of Aboriginal groups.Footnote 86 The hearings were generally open to the public, but hearings in Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia, were conducted with separate venues for the hearing and the public respectively.Footnote 87 The NEB's website served as a public record-keeper to the location details of the hearings, the transcripts, and the details of the participation process. In all, there were 180 days of oral hearings in 21 communities, featuring 175,000 pages of evidence, 9,500 letters of comment, and 1,179 oral presentations. In addition, 268 participants were allowed to cross-examine and 389 witnesses were put forward by intervenors.Footnote 88

[60] The Joint Review Panel's community hearings included one of relevance to this public interest investigation on January 28, 2013, in Kelowna, British Columbia. The final hearings were held in 2012 and 2013 in Edmonton, Prince George, and Prince Rupert for oral questioning, and oral final arguments were presented in Terrace, British Columbia. The final hearings that took place in Terrace on June 16 and 17, 2013, are also of particular relevance to the present report.

[61] The Northern Gateway Project attracted a great deal of public attention and scrutiny, particularly because of concerns about the environmental impact of a potential pipeline or oil tanker spill, and because the pipeline would cross lands currently and traditionally used by Aboriginal groups. Indeed, the British Columbia government opposed the Project in view of these concerns, and issued a number of corresponding conditions that would need to be met before it could support the Project.Footnote 89 Broad opposition by Aboriginal groups and environmental protection and conservation groups, among others, coalesced into organized movements to stop the Project. The Idle No More movement arose in part because of First Nations opposition to the Northern Gateway pipeline and the federal omnibus bills (Bill C-38 and Bill C-45) relating to it and other pipeline projects.Footnote 90 The NEB's Joint Review Panel hearings took place as that movement and other concerned groups opposed and conducted demonstrations against the Project.Footnote 91

[62] Shortly before the Joint Review Panel hearing in Kelowna on January 28, 2013, a series of protests took place in Vancouver during Joint Review Panel hearings being held there. In one instance, a group of roughly 100 Idle No More demonstrators massed outside the hearings amidst a day of national action by Aboriginal groups.Footnote 92 One protester was arrested after evading security and entering the lobby of the hotel on the first day of hearings. Furthermore, a group of five protesters were arrested after they snuck into and disrupted a closed-door hearing due to their concern about the environmental implications of the Project.Footnote 93 The Vancouver hearings also took place against the backdrop of an evening rally of 1,000 people in the city's Victory Square, with about half that number marching to the hearing site.Footnote 94 This resulted in "an increased anxiety level" within the NEB as it prepared for the Kelowna hearing and raised concerns that similar threats to disrupt the hearing process could arise, particularly since the panel, presenters, and the public would again be in one venue.

Threat Level

[63] The CIIT informed the Commission that, at the federal level, a comprehensive assessment relating to the Joint Review Panel hearings was not completed because there was no identified need (i.e. there was a very low level of criminal activity, or assessed potential for criminal activity, which did not indicate a requirement for such an assessment). However, some threat indications were noted at the "E" Division level:

- In January 2013, one "person of interest" sent e-mail messages to the NEB implying that he was willing to engage in violence to make himself heard at the hearings. Nothing came of these threats, however.

- Joint Review Panel hearings in Vancouver in January 2013 saw increased protests, with up to 1,000 persons attending, and (as noted above) included disruption of the hearings themselves. The Vancouver Police Department passed on an account to the RCMP that stated, "Approximately 20 masked up black clad anarchist rebels created a defiant contingent within the 600 to 1000 person anti-pipelines demo organized by ‘Rising Tide', on the evening of January 14th."

- On January 24, 2013, Corporal Dave AlbrechtFootnote 95 of the Kelowna RCMP Detachment General Investigations Section wrote in his notes that he was informed by a member of the "E" Division INSET that the "black bloc" (militant, potentially aggressive or violent black-clad protesters) had become more aggressive due to the fact that access to the hearings had been limited, which upset more people.

- The next day, Sergeant Steve Barton of the RCMP Criminal Intelligence Section sent an update to Corporal Albrecht, concerning threatening letters that had been sent to Enbridge and to TransCanada Pipelines Ltd. in "K" Division in Alberta. At that time, no link to British Columbia had been identified.

- When the Joint Review Panel released its report approving the Northern Gateway Project in December 2013, a Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chief of the Unist'ot'en protest camp expressed opposition to pipeline development in the area and reportedly stated that he was willing to stop it "by any means."

[64] Additionally, in January 2014, the RCMP's CIIT released an intelligence assessment of criminal threats to the Canadian petroleum industry. This was provided to the NEB. Its key findings (which the Commission references to indicate the RCMP's assessment) were that:

- The Canadian petroleum industry is requesting government approval to construct many large petroleum projects which, if approved, will be situated across the country;

- There is a growing, highly organized and well-financed, anti-Canadian petroleum movement, that consists of peaceful activists, militants and violent extremists, who are opposed to society's reliance on fossil fuels;

- The anti-petroleum movement is focused on challenging the energy and environmental policies that promote the development of Canada's vast petroleum resources;

- Governments and petroleum companies are being encouraged, and increasingly threatened, by violent extremists to cease all actions which the extremists believe, contributes [sic] to greenhouse gas emissions;

- Recent protests in New Brunswick are the most violent of the national anti‑petroleum protests to date;

- Violent anti-petroleum extremists will continue to engage in criminal activity to promote their anti-petroleum ideology;

- These extremists pose a realistic criminal threat to Canada's petroleum industry, its workers and assets, and to first responders.

[65] It should be noted that the protest actions concerning the Northern Gateway Project were generally peaceful, but it is in the context of the demonstrations, and the RCMP's understanding of the threat environment, that the events that form the subject of the BCCLA's complaint took place.

First Allegation: The RCMP improperly monitored activities of various persons and groups participating or seeking to participate in the National Energy Board hearings

a. RCMP Presence at the National Energy Board Hearings

[66] Among its specific concerns, the BCCLA contends that "RCMP members have maintained a visible presence at NEB hearings when there are no grounds for security concerns."Footnote 96

[67] E-mail messages and other documents provided to the Commission disclosed discussions regarding the RCMP being asked to provide a security presence for an NEB Joint Review Panel hearing held in Kelowna on January 28, 2013. The RCMP's assistance was requested in light of recent disruptions to prior hearings in Vancouver, and to ensure public and highway safety during planned Idle No More gatherings. An RCMP planning document concerning the hearing noted that a number of Idle No More protests had been joined by groups such as "Freemen of the land" and "black clad anarchist rebels," and that the recent protests in Vancouver that took place during the hearings there had quickly become "confrontational" towards the police.

[68] Several demonstrations were planned for the day of the hearing. The RCMP had been told by a representative of the Idle No More movement that the intention was to hold a peaceful rally, and the RCMP noted that a number of the hearing dates had taken place with minimal police involvement, but the RCMP nevertheless expressed concern that more militant protesters from across the province would attend. The NEB decided to hold a "closed door" hearing, with one venue for the hearing at a hotel, and another venue with a viewing room for the public at a separate, nearby hotel.

[69] Approximately 18 RCMP members in total were assigned to the event, stationed at the hearing venue hotel and along the route to the hotel, including uniformed and plainclothes members. However, while protests did take place on January 28, 2013, at the hearing site in Kelowna, they were peaceful and uneventful.

[70] The Commission noted in its review of the information provided that the RCMP objected to the apparent expectation that its members were to act like "security guards" for the NEB, which wished them to check identification and determine who would or would not have access to the hearing. The RCMP reiterated that its role was to keep the peace and to act only under lawful authority where, for example, an individual refused to leave when asked by the property owners. The RCMP's position at that time was that the threat level regarding the Kelowna hearing was low and that they had received no indication of violence being planned.

[71] The RCMP was also asked to provide a security presence for NEB Joint Review Panel hearings in Terrace on June 16 and 17, 2013, where the RCMP would keep the peace and enforce the law as required for the first two days of hearings. The Commission reviewed the NEB's security plan for the hearings (details of which the Commission will not disclose due to its security designation) and found that although no direct threats to safety and security had been identified, the NEB nevertheless assessed the risk of building occupations and demonstrations as high. The NEB requested that the RCMP provide uniformed and plainclothes members as a consequence. The Officer in Charge ("OIC") of the Terrace Detachment understood the RCMP as being obliged to assist the NEB.

[72] Of note, the Terrace Detachment's operational plan for the June 2013 Joint Review Panel hearings stated that the OIC would meet with the organizers to emphasize the importance of a peaceful rally, respecting the rights of all persons. The plan noted that the demonstrations that had occurred at prior NEB hearings had been peaceful and without major incident. The Terrace Detachment had been in contact with the Idle No More organizers and found them to be "most co-operative." The plan's objective stated, "Recognizing the democratic right to rally protest and demonstrate in a lawful and peaceful manner, as well as the legal authority for the National Energy Board to conduct orderly hearings into the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, the RCMP will maintain law and order with a measured approach." [Emphasis added]

[73] The first Idle No More rally took place at George Little Park in Terrace on June 16, 2013, which more than 300 people attended. RCMP members maintained a "low key, but visible presence with positive interaction, handing out RCMP tattoos, stickers, etc…to children in attendance." The event was peaceful and uneventful. Owing to the hot weather, the demonstrators did not march to the hearing site as originally planned. A further peaceful demonstration was promised for the next day.

[74] On June 17, 2013, about 70 people gathered to demonstrate outside the NEB Joint Review Panel hearing site with placards and drumming, and the RCMP again observed that the event was peaceful with no disruptions to the hearing. The Terrace Detachment determined that the measured approach taken to that point would continue, but a "significantly reduced" presence was anticipated for the remainder of the hearings. Indeed, the hearings concluded on June 24, 2013, without further incident, and the NEB was reportedly most appreciative of the RCMP's "outstanding" support.

[75] The BCCLA argues that "[c]ourts and tribunals conduct hearings every day across Canada without the presence of police or other security personnel."Footnote 97 Contrary to the complainant's assertion, however, legislation has been enacted across Canada that specifically provides for the presence of security personnel and for the overall security of the courts and members of the public.Footnote 98 Many courts and tribunals across Canada feature police, commissionaires, and even security screening. At the federal level, the RCMP Protective Policing Services are responsible for the safety of Supreme and Federal Court judges.Footnote 99 The Canadian Judges' Forum, a conference of the Canadian Bar Association, has also produced a restricted access report entitled Court Security in Canada, which is aimed at considering ". . . unique Canadian challenges for ensuring the safety of judges and other court personnel."Footnote 100

[76] Unlike most courts and many other tribunals across Canada, moreover, the NEB hearings present the considerable challenge of taking place in different buildings and settings, mainly hotels, which lack the physical security perimeter of a court or a tribunal that has a fixed location. Furthermore, as noted above, the Canada Labour Code obliges the NEB to ensure that all requirements are met for a safe public hearing.Footnote 101 In that context, the RCMP presence at the NEB hearings was initiated by the NEB based on an NEB security assessment that identified a high risk for building occupation and demonstrations, which had previously taken place in the context of NEB hearings. With safeguards in place that included an RCMP presence, the NEB reassessed the threat as medium.

[77] The Commission notes that the RCMP did not uniformly attend all hearings and information sessions, with member attendance being influenced by such factors as specific NEB requests, the threat environment, and unit resources. In one instance in the fall of 2013, the RCMP informed the NEB that they had no concerns about an upcoming information session and "would stop by [the venue] if time permitted." Ultimately, the RCMP did not attend and no active files were generated.

[78] After a careful review, the Commission does not find that the visible presence of RCMP members at the NEB hearings equated to improper monitoring in and of itself. Although the RCMP assessed the risk of criminal activity as low, it was reasonable for the RCMP to provide a service that would facilitate a safe public hearing; such services are offered by police and other security personnel across the country.

Finding No. 1: It was reasonable for the RCMP to provide a visible presence at the National Energy Board hearings.

b. Monitoring of a Protest at the Prince Rupert Courthouse

[79] In its complaint, the BCCLA states:

RCMP S/Sgt VK Steinhammer notified an NEB security officer of an Idle No More protest that was scheduled to take place on the Prince Rupert courthouse lawn on a Sunday afternoon. Despite confirming that the RCMP anticipated the protest would be peaceful, S/Sgt Steinhammer nevertheless advised that the RCMP would be "monitoring" this event. BCCLA is troubled that the RCMP would deem it necessary to monitor peaceful gatherings at which it has no expectation of criminal behaviour, threat to public safety or need to ensure the safety of demonstrators.Footnote 102

[80] As support for its allegation, the BCCLA makes reference to an e-mail dated April 19, 2013, from Staff Sergeant Victor Steinhammer (Operations Non‑Commissioned Officer ["NCO"] of the Prince Rupert Detachment) to NEB Security Group Leader R.G. The Commission reviewed the documentary materials, which confirmed the communication. The conduct of Staff Sergeant Steinhammer was identified as the subject matter of the complaint and, therefore, Staff Sergeant Steinhammer was given notice of the complaint. The chronology of the information is as follows:

- On April 18, 2013, Mr. G informed the RCMP by e-mail that the NEB senior management was expressing concerns about the possibility of violent protest activity surrounding the following two weeks of hearings in Prince Rupert. He asked if it would be possible for the RCMP to "step up" its visibility and have a uniformed presence for the first day or two of the hearings.

- On April 19, 2013, Inspector Peter Haring (Operations Officer, North District, RCMP "E" Division) sent an e-mail to Staff Sergeant Steinhammer asking him if he was aware of a planned Idle No More gathering at the Prince Rupert courthouse on April 21, 2013, and stated that the RCMP should inform the court and sheriffs of the event.

- On April 19, 2013, Staff Sergeant Steinhammer replied to Mr. G's April 18 e-mail, and stated that he had "received information of a planned peaceful Idle No More Protest on the courthouse lawn on Sunday April 21 @ 1400 hours." He told Mr. G that the Prince Rupert Detachment would be monitoring the event, and noted that the Facebook page for the event had "only 24 hits."

- On April 19, 2013, Staff Sergeant Steinhammer contacted an RCMP member named Nancy Roe, and asked her to let him know how the event went. She replied on May 2, 2013, and informed him that turnout was very low and that the RCMP members who attended remained for only about 30 minutes. They drove by later in the day and still saw only sparse attendance.

[81] The Prince Rupert Detachment monitored other protests in 2013, and it is worthwhile to note that Staff Sergeant Steinhammer seems to have recognized the peaceful nature of the demonstrations. In an e-mail dated January 11, 2013, to members of the RCMP, Staff Sergeant Steinhammer provided direction on a possible Idle No More protest at the Prince Rupert mall: "If this occurs, please attend, allow them to protest as they have been peaceful. You only intervene if something criminal takes place, and only if it is safe, you intervene." [Emphasis added] The protesters ultimately did not keep their pledge to not enter the mall, and were asked to leave by mall security. They did so without incident and there is no indication that the RCMP became involved. Of note, Joint Review Panel hearings that took place in Prince Rupert for several days in February 2013 occurred without continuous police presence and without incident. Further Joint Review Panel hearings later in February 2013 and in March 2013 also occurred without continuous police presence and without incident.

[82] The NEB sought information from Staff Sergeant Steinhammer on two other occasions identified in the materials provided. Following hearings in Vancouver in January 2013 in which the NEB "had a very busy time with protesters," and having "received intel that [they] may expect same in Kelowna next week," Mr. G asked Staff Sergeant Steinhammer on January 21, 2013, if there were any changes in the intelligence picture. This would assist the NEB in determining its security requirements for upcoming hearings. Staff Sergeant Steinhammer replied that the RCMP had received no intelligence with respect to the hearings. He suggested that the RCMP and NEB "take the same approach as the last set of hearings." An earlier exchange suggested that RCMP members were not present at the previous hearings.

[83] Additionally, on February 15, 2013, Mr. G asked Staff Sergeant Steinhammer if he had any threat information with respect to a group called "The People's Summit on the Northern Gateway Project" in the context of the Prince Rupert Joint Review Panel hearings. Staff Sergeant Steinhammer replied, "None at all."

[84] The information provided by Staff Sergeant Steinhammer to Mr. G was open source information (i.e. obtained from a publicly available source, and in this specific case the social media site Facebook). It was provided in response to a concern expressed by the NEB about potentially violent protests.

[85] The Commission appreciates that the BCCLA is troubled by the RCMP presence at the April 2013 protest, but even though the RCMP anticipated that the event would be peaceful (as it in fact was), protests and demonstrations are of a dynamic nature and even a lawful assembly has the potential to become an unlawful one. The standard against which the conduct of the RCMP is assessed is one of reasonableness in the circumstances. Given the RCMP's mandate to maintain peace and order and to prevent crime, it was not unreasonable to send members to monitor the event and confirm that it remained a peaceful one.

Finding No. 2: It was reasonable for the RCMP to monitor the Prince Rupert protest.

c. Monitoring of Protests by the Critical Infrastructure Intelligence Team

[86] The BCCLA alleges that Tim O'Neil, a temporary civilian employee Senior Criminal Intelligence Research Specialist (now retired) with the RCMP's CIIT, improperly monitored the activities of groups that it did not suspect of any criminality. Specifically, the BCCLA is concerned that:

Despite confirming that CIIT has no intelligence indicating a criminal threat to the NEB or its members, O'Neil advises that "CIIT will continue to monitor all aspects of the anti-petroleum industry movement," requests that an SPROS/SIR National Security database file be opened for this matter, and notes that this information is also being shared with CSIS. Again, BCCLA is troubled that the RCMP and CSIS would deem it necessary to monitor the activities of groups which it does not suspect of any criminality.Footnote 103 [Emphasis in original]

[87] Mr. O'Neil's conduct was identified as the subject matter of the complaint and therefore Mr. O'Neil was given notice of the complaint. It should be noted that Mr. O'Neil was appointed under Part I of the RCMP Act as it read prior to being amended on November 28, 2014.Footnote 104 This meant that the RCMP Act, as it read at the time of the complaint and the commencement of the public interest investigation, made temporary civilian employees like Mr. O'Neil subject to the complaint process under Part VII of the RCMP Act.Footnote 105 Although the November 2014 amendments to the RCMP Act repealed the provision that allowed for the appointment of temporary civilian employees, the complaint was filed in February 2014 and this public interest investigation commenced in February 2014. Accordingly, Mr. O'Neil's actions were subject to the Commission's review under the previous RCMP Act. Moreover, the amended RCMP Act gives the Commission jurisdiction to receive complaints about persons who were appointed or employed under the RCMP Act at the time that the conduct complained of is alleged to have occurred.Footnote 106 As this would clearly include persons who were appointed or employed under the RCMP Act as it read prior to November 2014, the Commission concludes that it has the jurisdiction to consider Mr. O'Neil's conduct.

[88] The relevant material of concern with respect to this specific sub-allegation is an e-mail dated April 19, 2013, in which Mr. O'Neil responded to a request for assistance from Mr. G of the NEB to determine whether a credible threat existed against NEB panel members. The NEB was concerned about a YouTube video and other websites that discussed the NEB. Mr. O'Neil noted that he had detected no direct or specific criminal threat, and that the CIIT had no intelligence indicating a criminal threat to the NEB or its members.

[89] After a careful review, the Commission notes that only an incomplete extract from Mr. O'Neil's e-mail was inserted into the specific allegation. This had the effect of taking Mr. O'Neil's response out of context. The full text states: "CIIT will continue to monitor all aspects of the anti-petroleum industry movement to identify criminal activity, and will ensure you are apprized accordingly." [Emphasis added] To provide background to this statement, Mr. O'Neil observed that the ongoing opposition to petroleum and petroleum pipelines included both lawful and unlawful actions. The unlawful actions included vandalism, sabotage, and threats to property and persons. He noted that activists had previously engaged in coordinated mass participation in regulatory hearings to overwhelm the assessment process, resulting in the hearings being "bogged down" on occasion. The corresponding efforts of the federal government to limit who may make formal presentations at the NEB's public hearings had the result of making the conduct of the hearings themselves the focus of protest activities, and made the NEB and its members the subjects of protest rhetoric. Additionally, due to the NEB's role as the federal regulator for many aspects of petroleum and petroleum pipeline projects, it had also become a focus of opposition attention, and Mr. O'Neil concluded that it "is highly likely that the NEB may expect to receive threats to its hearings and its board members."

[90] The purpose of the monitoring is significant; the CIIT is required to identify and investigate criminal threats to critical infrastructure, and the RCMP more broadly is required to identify and investigate criminal threats to public events such as the Joint Review Panel hearings. Had the RCMP indeed undertaken to monitor the entire "anti‑petroleum movement" without regard to the right to peaceful dissent, such activity might have been unreasonable. However, it is clear that with the added context of criminal threats to critical infrastructure and the NEB and its members, and the stated purpose of identifying criminal activity, the RCMP monitoring was to be confined to purposes within its law enforcement mandate.

Finding No. 3: It was reasonable for the RCMP to monitor events for the purpose of identifying criminal activity.

d. Monitoring by Unidentified Members of Various Persons and Groups seeking to Participate in the National Energy Board Hearings

[91] The BCCLA is troubled about allegations concerning the RCMP's "improper and unlawful actions . . . in gathering information about Canadian citizens and groups engaging in peaceful and lawful expressive activities . . . ."Footnote 107 It further states:

Police monitoring may also deter those who simply wish to meet with or join a group to learn more about a matter of public debate or otherwise exchange information or share views with others in their community. Indeed, BCCLA has already heard from several of the affected groups that members and prospective members of their organizations have expressed serious concerns and reluctance to participate in light of recent media reports of RCMP monitoring.Footnote 108

[92] The RCMP's CIIT reported that it is not aware of specific efforts by the RCMP to gather information about, or monitor the activities of, any persons and groups who wanted to participate in the NEB hearings. The CIIT stated that if any information about a criminal threat were to surface as part of an investigation or from another source (i.e. an e-mail request from the NEB), the CIIT, as part of the RCMP's law enforcement mandate, would make an initial examination to determine if there was any criminal component to the identified activity or material. If there was no identified criminal component, the information would not be further examined or pursued.

[93] The CIIT informed the Commission that it has no records of information being gathered by the RCMP on various persons and groups seeking to participate in the NEB hearings.

[94] However, the materials before the Commission reveal that the RCMP monitored protests and demonstrations at the "E" Division level. Additionally, the materials reveal that the RCMP video-recorded some of the public protests and demonstrations.

i. RCMP Monitoring and Video-Recording of Protests and Demonstrations

[95] On January 28, 2013, an Idle No More flash mob round dance intended to draw attention to Bill C-45 and the Joint Review Panel hearings was organized in Vernon, British Columbia. It was advertised via Facebook, among other means. The organizer of the event contacted the Vernon Detachment to request a police presence at what he anticipated would be a peaceful event that would include elders, children, and the patrons of the shopping mall where the event would be taking place. The RCMP did attend to monitor the situation; approximately 70 people participated in the flash mob, and the RCMP noted that the event was peaceful and that it concluded without incident.

[96] As discussed above, a protest took place at the Joint Review Panel hearing site in Kelowna on January 28, 2013. Approximately 135 people attended in total, and RCMP members were present, but it was peaceful and uneventful. Of note, a member of the Kelowna Detachment Forensic Identification Section attended the demonstration at the hotel where the hearing was held, recording approximately 10 minutes of video footage of the event from a hotel room on the top floor.

[97] Again, as discussed above, on June 16, 2013, a rally took place in George Little Park in Terrace, where some 300 demonstrators assembled and listened to speakers. The RCMP attended, maintaining a "low-key, but visible presence with positive interaction. . . ." There are no indications that this event was video-recorded.

[98] On June 17, 2013, the RCMP monitored a second day of demonstrations in Terrace and noted that it was a peaceful event. This is also described above. However, the general occurrence report concerning the event reveals that a member of the Terrace Detachment Forensic Identification Section attended the scene (the Best Western Plus Terrace Inn, where the Joint Review Panel hearings were taking place) for the approximately one-hour duration of the demonstration, and recorded the event. The recording was saved as a DVD.

[99] On July 1, 2013, an Idle No More gathering was organized at the City Park in Kelowna. An RCMP member contacted one of the organizers of the event and was informed that the gathering was expected to be peaceful and that the organizers would be providing their own security. An RCMP First Nations Policing member worked closely with the organizers on the day of the event, which was peaceful and uneventful.

[100] The RCMP's "E" Division Aboriginal Policing Services compiled a spreadsheet of British Columbia Idle No More events held in December 2012 and throughout 2013. The spreadsheet recorded the date, location, and size of the event, along with the detachment or police service of jurisdiction, details about the event, and nearby infrastructure or vulnerabilities. Over 220 events (some of which never took place and were listed only as plans or unconfirmed) were listed, including rallies, road blockades, flash mobs, marches, information sessions, demonstrations at Joint Review Panel hearings, round dances, and concerts. There was no indication of the extent of what police presence, if any, may have been required for the events, and no identifying details regarding organizers or participants were included in the spreadsheet.

[101] In assessing the reasonableness of the RCMP's actions, the Commission notes that the RCMP's monitoring and internal reporting (e.g. preparing briefing notes) is consistent with RCMP policy, including its policy regarding Aboriginal demonstrations or protests.Footnote 109 For example, the RCMP Operational Manual states:

1.1 The RCMP's primary role in any demonstration or protest is to preserve the peace, protect life and property, and enforce the law.

. . .

2.2. "A [p]eaceful protest, peaceful assembly and freedom of expression are all fundamental rights as defined under Part I, sec. 1, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

2.3. A measured response based on accurate and timely intelligence must form the basis for the management of aboriginal demonstration or protest.Footnote 110 [Emphasis added]

[102] As indicated above, the dynamic nature of protests and demonstrations means that it is generally appropriate for police to monitor these events to ensure public safety and to be prepared in the event that unlawful activity occurs. Again, given the RCMP's mandate and duty to maintain peace and order and to prevent crime, the Commission is satisfied that the RCMP acted reasonably in monitoring the above-noted demonstrations.

Finding No. 4: The RCMP acted reasonably in monitoring the demonstrations.

[103] With respect to the RCMP practice of video-recording protests, video surveillance can in some circumstances constitute a police searchFootnote 111 within the meaning of section 8 of the Charter,Footnote 112 which protects against unreasonable search or seizure. However, police conduct will only rise to the level of a search where the affected person has a reasonable expectation of privacy.Footnote 113 In that vein, the RCMP Operational Manual and the "E" Division Operational Manual state that where there is no reasonable expectation of privacy, a judicial authorization (warrant) for video surveillance may not be required.Footnote 114

[104] Additionally, even where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy, it is only unreasonable searches that are impermissible; a search authorized by law and carried out in a reasonable manner will not offend section 8.Footnote 115 Accordingly, there are two distinct questions that must be addressed regarding police searches and the expectation of privacy: first, whether the individual concerned had a reasonable expectation of privacy; and second, whether the search was an unreasonable intrusion on that right to privacy.Footnote 116

[105] It is not the role of the Commission to make a finding as to whether a Charter right has been infringed. That role belongs to a court of competent jurisdiction. The Commission may, however, determine whether RCMP conduct is reasonable and consistent with Charter principles. The Commission begins its analysis with an assessment of whether there was a reasonable expectation of privacy; only if a reasonable expectation of privacy is found will the Commission consider whether the RCMP's conduct was consistent with the principles underlying section 8.

[106] Whether an expectation of privacy is reasonable or not must be assessed in the totality of the circumstances of a particular case.Footnote 117 It includes an assessment of whether there was a subjective expectation of privacy and whether that expectation was reasonable in the circumstances.Footnote 118 This requires "value judgments" from the "perspective of the reasonable and informed person who is concerned about the long‑term consequences of government action for the protection of privacy."Footnote 119 Significantly, however, the more that the information concerned touches on an individual's biographical core, the more the balance will weigh in favour of a reasonable expectation of privacy. The "biographical core" refers to personal information "which individuals in a free and democratic society would wish to maintain and control from dissemination to the state. This would include information that tends to reveal intimate details of the lifestyle and personal choices of the individual."Footnote 120

[107] Although the RCMP engaged in video surveillance of public protesters, one's public activities can be subject to a reasonable expectation of privacy. The Supreme Court of Canada has found that public activities can attract a privacy expectation where, for instance, the government engages in continuous surveillance of that activity, such as in a case where an individual was continuously tracked while driving a vehicle on public highways.Footnote 121 Individuals generally expect a degree of anonymity when in public places, free from identification and surveillance. This is because of the value of what has been called "public privacy."Footnote 122 In the context of section 8 of the Charter, the Supreme Court of Canada has also concluded that anonymity is one conception of informational privacy because it permits individuals to act in public places while preserving freedom from identification and surveillance.Footnote 123 The Court stated, "The mere fact that someone leaves the privacy of their home and enters a public space does not mean that the person abandons all of his or her privacy rights, despite the fact that as a practical matter, such a person may not be able to control who observes him or her in public."Footnote 124 Accordingly, depending on the totality of the circumstances, anonymity "may be the foundation of a privacy interest that engages constitutional protection against unreasonable search and seizure."Footnote 125

[108] Additionally, while it is relevant to the analysis to ascertain whether police searches take place in the context of information, things, or activities that have been hidden from view, the Charter protects against searches where society agrees that the object of the search should be kept out of the state's hands unless there is a constitutional justification. The Court of Appeal for Ontario observed in R v Ward that the reasonable expectation of privacy requires asking more than whether the claimant had a subjective expectation of privacy and whether in all the circumstances that expectation was reasonable: