Police Investigating Police: A Critical Analysis of the Literature

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Researchers:

Dr. Christopher Murphy

Mr. Paul F. McKenna

Table of Contents

Part I – A Critical Analysis of the Literature

- PIP: General and Specific Trends

- Core Police Investigating Police Issues & Controversies

- PIP Models, Types & Variables

- Knowledge & Research Gaps

- Conclusion

Introduction

Current public and political debate about the desirability and effectiveness of police investigating complaints against the police or allegations of misconduct, have reached a critical juncture in Canada and in many other Western countries. In Canada, a variety of recent public incidents or situations in which police judgments or actions have been called into question raise fundamental concerns about police accountability and governance. In the last few years events such as the inquiry into the case of Maher Arar (Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar, 2006), the RCMP pension scandal (Brown, 2007), the ongoing controversy surrounding the use of conducted energy weapons (Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP, 2008) and, most recently, the substantial recommendations of the Taman Inquiry (Taman Inquiry into the Investigation and Prosecution of Derek Harvey-Zink (Manitoba), 2008) have generated major public concern and political debate. Central to this debate are basic questions regarding the role and fairness of the conventional practice of police investigating complaints and incidents regarding their own behaviour or actions. Other questions address the relative effectiveness of various police investigative and oversight strategies and explore possible alternatives that might better satisfy the demands of public accountability and procedural justice.

These are some of the questions this report explores through a review of the available national and international academic and policy literature. This examination addresses both the theory and practice of police investigating police (PIP) in oversight situations. This commissioned study has been asked to identify this literature in the form of an annotated bibliography and to conduct an analysis of this literature by providing a critical discussion of investigative trends, critical issues, alternative models, research gaps and suggestions. It is hoped that the information and analysis provided in this report will establish an informed basis for further discussion and development leading to more effective and publically acceptable methods and models for the investigation and review of police-related complaints; a critical contribution to the maintenance of public confidence in the police.

Part I: Critical Analysis of the Literature

Preamble

The following section of this report is a critical discussion of the relevant academic and policy literature focused on police investigating police (PIP) in the context of public complaints against the police as part of internal or external oversight and review processes. While the academic literature is extensive on issues concerning police accountability, governance and investigation, it is strikingly limited with respect to direct empirically-based research and analysis of the actual practice of police investigating police. The literature is also scant in terms of comparative or evaluative studies of different investigative PIP models and strategies. To the extent that these issues are addressed, we provide an annotated bibliography thoroughly addressing twenty-six (26) directly relevant academic and policy documents on PIP. In addition, we have cited a number of more general but related academic and policy publications which provide background and context for this more focused discussion on PIP.

The following review critically assesses the body of national and international academic literature on PIP by:

- Examining the relevant contextual social and legal trends that set the parameters for recent PIP developments and describing specific trends in the evolution of various models of police investigation and governance;

- Identifying a variety of domestic and international models and types of police investigating police and governance relationships and developing a typology of five (5) distinctive PIP model types;

- Describing a number of critical problematic issues identified in the literature; and

- Identifying key knowledge and research gaps in the literature and providing a number of suggestions for future research.

1. PIP: General and Specific Trends

It is easier to understand and predict the evolution of the police role in the investigation of complaints against the police and police governance by placing PIP development and trends into a broader social and political context. The following narrative on the evolving role of police in the complaint review and investigation process suggests that the key drivers of change and development in civilian and police review are located in broader global social and political shifts in political governance, public knowledge and attitudes towards authoritative institutions like the police. The following are some of the social and political trends that will shape the direction and future role of the police in the context of civilian review.

General Accountability & Governance Trends

1.1 The New Police Accountability

In a useful article on the changing nature of police accountability and growing public and political demand for more effective forms of police accountability Chan (1999) suggests that there has been a shift toward the adoption of private sector and new public management approaches to police accountability. Based on a neo-liberal critique of traditional government and the management of public services like the police, new philosophies and forms of internal self governance are being proposed. Chan argues that the general political governance of the police, at least in Australia, is shifting away from traditional models of reactive accountability which depend upon the application of external legal rules, hierarchical and central regulation and punishment centered discipline. This old model of public accountability or review has failed to provide adequate police accountability primarily because of the resilient and resistant nature of occupational police culture and its inability to change or control it. The new police accountability is part of a more general trend toward a new public sector managerialism that emphasizes closely managed self-regulation and governance, reinforced by external oversight. Police organizations are being more closely managed and scrutinized internally by a labyrinth of management systems, technologies and procedures and externally by more elaborate public complaint systems and auditors. The new accountability moves away from "punishment and deterrence" towards "compliance" and modes of regulation aimed at "preventing harm" and "reducing risk," through tighter regulation, audit, surveillance and inspection. While the old accountability is seen to have failed, the new accountability has also not been very successful, but Chan argues that it may gradually succeed as modes of internal self-governance and self-regulation are more acceptable to police culture than more traditional, legalistic, external accountability measures. In short, it is the opinion of Chan and others that the future of police accountability lies in more elaborate and effective modes of "internal management and self-governance" and not in more intricate and powerful forms of external governance and control.

1.2 The Rationalization of Autonomy & Self-Governance

In this postmodern era the privileged status and powers of professions and their claim to self-regulation and operational autonomy are under attack. Academics such as Freidson (1984) and Reiner (1992) argue that as part of a general post-modern skepticism about all authoritative institutions, traditional claims by professions such as medicine, law, and education for operational autonomy are being challenged by increasing public and political demands for more demonstrable accountability. The traditional, largely informal, self-regulation of professional activities is no longer seen as acceptable to an increasingly skeptical public and for neo-liberal governments. Professions are increasingly being asked to justify their traditional privileges and powers by providing more formal, detailed and structured accounting of the exercise of their discretionary powers. The expansion of internal accountability through more elaborate formal self-regulation would appear to be the price of autonomy for all professions in the new postmodern era.

Police claims to autonomy and self-regulation are in part a function of their special legal powers and the threat of undue political control, but this claim is also based on a persistent if not always credible claim to professionalism. Professional credibility relies on convincing displays of effective, fair and appropriate regulation and control of the activities of one's members. While police share certain qualities of a profession, they fail to meet some of the essential standards such as an effective and credible "internal" disciplinary and ethical system as well as a scientific and academically verified knowledge base that informs their practice. The problematic nature of PIP and the development of external civilian review suggest that the police have not been able to demonstrate either the willingness or the ability to govern the behaviour of their members at least in ways that create public and political confidence. Whether the police are professional or not, they will increasingly be required to document, regulate and justify their autonomy. This political trend will affect police if they wish to maintain even their current level of self-governance and control. This global trend towards the expansion and formalization of internal accountability and the increasing regulation of operational autonomy is pervasive in Western government and will influence the development of new models of police accountability and governance.

1.3 Increasing Public Criticism of the Police

While general public attitudes towards the police in most Western countries remain generally supportive, there has been a recent shift in public and political discourse regarding police governance of their own behaviour, especially deviant behaviour. Though reflective of more general suspicion of all authoritative institutions, the misuse or the abuse of police powers and police corruption have lately been central to public discourse and discussion in all of these countries. This shift in public discourse is usually stimulated by high profile incidents or cases and leads to questions regarding the desirability and effectiveness of police regulating their own actions and behaviour. While this may be a result of the increased visibility and newsworthiness of police-related abuse stories rather than a reflection of an actual increase, it has drawn attention to the increasingly anachronistic police claim for autonomy and control over their complaints review and investigative processes.

The recent development of a public and political culture of individual rights and civil liberties in most Western countries has meant more open and public criticism of police behaviour, especially as it relates to minorities. Communities and groups are now organized to represent special publics who can mobilize community opinion and discourse critical of police practice and in support of more legal and external regulation. In an increasingly diverse Canada it is reasonable to assume that this trend toward special interest group concerns about legal or civil rights and race-related or minority allegations will increase public support for more aggressive civil regulation and governance of the police. Governments as a result will be forced to recognize these new and more aggressive public demands for police accountability.

1.4 Increased Media & Public Scrutiny of Policing

Police work, until recently, has been a largely secretive occupation, out of the public eye and beyond critical media examination. Most accounts of police activity were dependent upon the police themselves and by and large the coverage was favorable and limited. The media were content to report and endorse police accounts of their own activities, and there was little interest or ability to offer alternative accounts. This distance from, and respect for, the police has changed and a media emphasis on drama and crisis has made the police newsworthy. More independent and informed reporting has meant far more aggressive, questioning and critical press coverage for police and perhaps a more realistic appraisal of their important but sometimes flawed occupation. This demystification of policing and police work by the media is similar to the demystification of other occupations in areas such as politics, law, medicine, education, etc. However this trend in critical media reporting and coverage is likely to continue and make it even more difficult for police to project or manage accounts of their activities. Thus the trend towards a more aggressive and critical media environment will continue to shape the politics and the dynamics of civilian review and the police role within it.

A related, but important trend is the increasing surveillance of police activities through public technologies such as video cameras and video-phones. Their enormous popularity has added a critical "new media" to the scrutiny of police activities. Police actions that were once private are now on public display for anyone with a television or an internet connection. For example, current public outrage and policy change over the use of conducted energy weapons by RCMP police were clearly animated by means of a random bystander's video-phone. The growing pervasiveness of the technology of public surveillance means that the police themselves are increasingly being monitored by the public making it even harder to protect themselves from public criticism, review or opinion (Ericson and Haggerty, 1997). The increasing new media scrutiny and surveillance dramatically amplifies incidents and elements of police deviance, feeding public arguments for more civilian review and regulation.

Specific Police Investigating Police Trends

The following section provides a descriptive account of the evolution and development of different trends in both police investigation and governance. Though largely historical in sequence, these trends must be seen in terms of the broader set of social and political circumstances under which they developed, and also, as responses to one another. The three investigative PIP trends described below, while products of different eras and distinct circumstances, all continue to exist in some form or another in various national and international settings.

1.5 Trend – The Developing Critique of Traditional Internal Police Systems of Investigation & Oversight

During the period up to, and including, the 1960s and 1970s, police departments traditionally dealt with public complaints and police officer discipline or misconduct concerns through entirely internal disciplinary systems (Goldsmith and Farson, 1987; Kappeler et al., 1994; Smith, 2004; Yeager, 1978). Police departments had internal affairs or professional standards units that discerned and investigated instances of misconduct, brutality or corruption and made recommendations on resulting discipline or sanctions. There was essentially no public oversight or involvement in these systems, processes, or procedures and little or no accounting for such actions outside of the department. Public complaints were treated with varying degrees of credibility, with virtually no assurance that they would be pursued, investigated or resolved in a manner that would meet current standards of accountability or transparency. This internal police system approach continued throughout the period conventionally referred to as the 'Professional Era' advanced by O.W. Wilson (Bopp, 1977) and included a conviction that police organizations could be managed by the principles of scientific management formulated for both public and private corporations (Taylor, 1947). Supporting the inward focus of the internal police system was an argument that police independence was a necessary adjunct to police professionalism in order to buffer police organizations from undue political interference and influence. The acceptance of police independence as a necessary condition of police professionalism was widespread in North America (Stenning, 1981, 1995). Virtually every police department tasked internal affairs units with full responsibility for the detection, investigation and response to instances of police misconduct (however defined). Discipline itself was typically a function of the chief of police and there was little right of appeal for any such disciplinary decisions.

This early approach to the investigation and oversight of public complaints may be characterized as a closed system entirely governed by police investigating and disciplining themselves (Barton, 1970; West 1988). Furthermore, it was largely, a system activated in the first instance by the police, regardless of whether or not a member of the public lodged the original complaint, since the intake processes were significantly at the discretion of the officer (usually a desk sergeant) who would receive the complaint (Brown, 1988; Colaprete, 2007; Fogel, 1987). However, it is useful and significant to highlight the considerable skill levels required for police officers to conduct any form of investigation in order to operate as an "effective detective" (Smith and Conor, 2000).

The critique of this closed approach began to emerge from public, political and academic sources. Members of the public, especially from minority communities in both Canada and the United States, were dissatisfied with the failure of police managers to adequately, systematically and effectively deal with legitimate complaints (Berman, 1981; Culver, 1975; Finnane, 1990; Goldsmith, 1991; Kerstetter and Rasinski, 1994). Politicians at municipal, provincial and federal levels were frequently motivated by pressures to seek reforms in the manner in which police organizations handled high-profile incidents that appeared to be instances of police brutality, corruption or misconduct. Academic research driven by the evolving discipline of criminology produced a number of revealing research studies on street police work (Skolnick, 1994 ) and police organizations (Wilson, 1973) which fuelled a growing critique of police discretion and the discovery of an insular but powerful police culture (Liederback et al., 2007). Research also indicated that detectives often concealed questionable or illegal police conduct from the public (Corsianos, 2003)1. Others research (Newburn, 1999) pointed to a lack of leadership from police administrators in not providing the funding and investigatory resources necessary to sustain a competent complaints investigation process. This increasingly critical focus on PIP generated new pressure for police managers to justify and explain the ethics and efficacy of their operating approaches to public complaints, especially in light of the persistent problem of police misconduct. Several high-profile grand jury hearings, Royal Commissions and commissions of inquiry in Canada, the United States and elsewhere worked to undermine and excavate the limitations of that closed system (Hudson, 1971). The McDonald Commission in Canada and the Knapp Commission in the United States are prime examples of major crisis points leading to fundamental reform in the investigation and oversight of police organizations (Commission of Inquiry Concerning Certain Activities of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1979; New York City Mayor's Commission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption, 1973).

Combined with the sources of critique outlined above, the growing importance of the media as an ongoing source of challenge to the internal police system should be acknowledged. This sustained fourth estate attack on police misconduct was augmented by a growing civil rights movement in the United States and a developing civil liberties sensibility in Canada. Often all of these actors found cause to coalesce around a particular precipitating event that would create serious challenges to the conventional wisdom of police independence and make highly problematic the precise practice of police investigating police. Accordingly, in many jurisdictions, the outcome of such events was a concerted call for police reform. Such reform frequently expressed itself in various approaches to civilian review of police activity. In the early 1980s, it has been determined that 83.9 per cent of United States police departments had exclusively internal complaints mechanisms (West, 1988).

1.6 Trend – The Development of Systems of Civilian Review of Police Investigation & Oversight

The second trend under consideration encompasses civilian review, developed in the 1970s in Canada, the United States and other jurisdictions. It is often seen as a manifestation of a developing concern for civil liberties and greater public accountability for all public organizations, particularly the police (Goldsmith, 1988, 1991; Landau, 1996). Dissatisfaction with the efficacy of the professional era of police management was particularly focused on the failure of police officers and their leaders to take seriously the legitimacy and pervasiveness of public complaints (Adams, 2003). Regardless of the existence of internal affairs units and professional standards sections, public, political and academic observers were concerned that police organizations were not fully committed to the principles of accountability and responsibility for the full range of police misconduct. As a result various oversight bodies designed to limit the independence of police in the form of civilian review were developed. For example, in several jurisdictions, a civilian body would be established that would undertake an examination of a completed investigation conducted on an internal basis by police officers within that department (Barton, 1970; Culver, 1975; Prenzler, 2000; Walker and Bumphus, 1992). Most civilian review models had the following powers:

- Citizens investigate public complaints and make recommendations to the chief of police;

- Police investigate public complaints and report findings; citizens review findings and make recommendations to the chief;

- Complainants appeal findings to a civilian body which reviews and makes recommendations to the chief; and

- Auditors investigate the process by which the police arrived at findings and report on the fairness and thoroughness to the police and the public (Finn, 2001).

Therefore, the police investigating police approach would be sustained with the additional element of a review of that investigation by civilians representing municipal, provincial/state, federal authorities and/or community interests. Clearly, this approach relied extensively upon the adequacy and sufficiency of the original investigation and the civilian review board would have little, or no, independent capacity or authority to authenticate or validate the quality, scope or sufficiency of the completed investigation (Bobb, 2000; Prenzler and Ronkin, 2001)2.

This trend towards civilian review was regarded as a provocation by many police leaders and became a major cause of controversy for police associations, who worked to activate their considerable financial, legal and public relations resources to undermine and discredit the legitimacy of civilian review (Littlejohn, 1981). Police arguments against civilian review include the view that they violated an officer's fundamental rights as a citizen, as violations of due process and equal protection clauses leading to 'double jeopardy' concerns (Barton, 1970). They also observed that these civilian review boards took management responsibility away from chiefs of police and the presence of civilians within the complaints process was a cause of lowered police morale. Attempts to substitute civilian for police participation in the investigation or disciplinary process police argued would lead to serious difficulties (Lewis, Linden and Keene, 1986; Walker, 1998).

For example, in Canada, the Civilian Independent Review of Police Activity (CIRPA) grew out of a serious and sustained concern that police in (then) Metropolitan Toronto were not being controlled by their senior officers and that instances of brutality and misconduct were going unpunished and underplayed (McMahon and Ericson, 1984). Several major events were viewed as catalysts in the increasingly persistent call for some consistent, coherent and compelling approach to independent civilian review of the actions of individual police officers (Lewis, Linden and Keene, 1986). Beginning with such cooperative efforts, Toronto became a watershed for a growing focus on civilian review that has evolved to the point of the final two police trends outlined below (Landau, 1996; Lewis, Linden, and Keene, 1986; McMahon and Ericson, 1984; Watt, 1991). The police union response to CIRPA, and other mechanisms for police oversight through civilian review, was predictably vociferous and critical.

Given this police response it is perhaps not surprising that, despite high public expectations, the promise of a robust and effective civilian review of police complaints has proven to be elusive (Finn, 2001). Police oversight bodies such as the Ontario Civilian Commission on Police Services, the British Columbia Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner, the Police Complaints Authority (Philadelphia), among others, all appeared to be constrained in their activities by a process which allowed them to simply review completed police investigations and make ex post facto assessments of the adequacy, fairness, and accuracy of those concluded investigations. This limited review approach was not satisfactory for either police practitioners or police critics and there were calls for more aggressive and effective review, independent of police involvement at both the investigative and/or adjudicatory stages.

1.7 Trend – Toward "Independent" Civilian Methods of Investigation & Oversight

The current trend toward civilian-based investigative models developed largely as a result of growing public and political frustration. This was combined with an increasing awareness of the limits of civilian review of PIP investigations and their apparent limited ability to produce results that would provide compelling public accountability, transparency and independence. The lack of civilian involvement in and control of the investigative process that sustains public complaints and their subsequent reinvestigation was seen to undermine the credibility and utility of civilian review, and indeed any model of police oversight and public covalence. This trend toward more independent and aggressive civilian involvement in both investigations and direct oversight has been developing since the late 1990s and incorporates different approaches that advance a transformed understanding of the entire policing enterprise. However, both of these investigative models go beyond civilian review of police investigations toward the direct involvement of civilians in the investigation and adjudication of those cases. The more radical civilian oversight model argues in favour of a completely independent "civilian" (i.e., non-police) control over the intake, investigation and response to public complaints of police misconduct.3

The final approach begins to take clear shape in the late 1990s and into the present century and incorporates two fundamentally similar approaches that advance an importantly modulated understanding of the policing enterprise. The similarities these approaches share are overshadowed by their conceptual differentiation based upon an understanding of the practical realities of policing within a modern public administration context. One method argues in favour of a completely independent approach to the intake, investigation and response to public complaints of police misconduct, while the other pursues a hybrid or "team" concept of oversight which includes police investigators combined with civilian counterparts jointly assigned with the task of interviewing, interrogating and investigating public complaints (Harrison and Cunneen, 2000; Thomassen, 2002). Both methods are currently in place in several jurisdictions. For example, the Police Ombudsman of Northern Ireland (PONI) and the Ontario Special Investigations Unit (SIU) present themselves as examples of completely independent oversight bodies. The Office of Professional Accountability in Seattle, Washington offers an unusual team approach, where a civilian attorney heads a unit that includes a captain, a lieutenant and six sergeants. However, the director reports within the police department to the chief of police (Bobb, 2000). The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) in Great Britain is an example of a team approach with independent civilian investigation managers, seconded senior police investigators, teams with a suitable mixture of police and non-police (initially with no police powers) members to provide the optimum in both performance and public confidence (Home Office, 2000). The IPCC could directly investigate or supervise investigations complaints (IPCC, 2008). The consent decree approach taken in the United States offers an interesting example of where the federal government, through the Department of Justice, intervenes directly and decisively in the administration and operation of a police department in response to concerns about the adequacy of investigations into public complaints4.

In summary, our analysis of existing academic and policy literature suggests that there is a discernable trend away from traditional PIP models in Canada and other jurisdictions. This trend seeks to move beyond police control of the investigative and adjudicative processes toward more direct and expansive civilian involvement in the investigation of complaints against police as well as the adjudication of outcomes. This trend will continue as the social and political conditions driving both the demand for more accountability and transparency in all authoritative agencies, not just police, will not likely diminish and the circumstances that produce complaints will most likely also not change (Travers, 2007). It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the trend toward greater civilian involvement will continue unabated. It would seem that the issue is no longer whether civilian review is desirable or possible but how civilian involvement in the investigation and disciplinary process can be most effective in satisfying public accountability while also obtaining the police cooperation necessary for good internal investigations (Hutchinson, 2005). The debate about the relative merits of different independent civilian or hybrid civilian models of police investigation and governance promise to dominate the immediate future.

2. Core Police Investigating Police Issues & Controversies

The following outline represents an attempt to identify from the literature some of the core problematic issues and controversies relevant to police investigating police that are central to current debates in the academic and policy literature. Our reading of this literature suggests the following core issues will be central to any future reform or developments in this area of public policy.

2.1 Is it possible for police to provide fair and effective investigations of themselves?

This issue deals with the central problem of whether it is possible for police to provide fair and effective investigations of complaints against themselves. It represents the core, central issue in all discussions of police governance and review models. There are a variety of political, academic and legal arguments (Goldsmith, 1988; Harrison and Cunneen, 2000; Landau, 1996; Littlejohn, 1981; Ontario Ombudsman, 2008; Seneviratne, 2004) that suggest that under normal circumstances police cannot provide adequate and impartial investigations of their own misconduct. There are a variety of arguments central to this criticism based on academic research as well as various boards and commissions of inquiry. Generally they have demonstrated that police officers and their organizations represent an insular and protective occupation with a distinctive and powerful organizational culture. This culture is in part designed to protect officers and the organization from external criticism and review by defending and rationalizing police officer misconduct. Police officers, in order to function are influenced and constrained by this culture and its demands for loyalty and solidarity against external criticism and review (Bennett and Corrigan, 1980; Loveday, 1987). PIP's failure to produce transparent and satisfactory findings has meant a loss of public confidence in PIP investigations and police-determined complaint review processes.

The counter argument is that police can and do in many cases provide fair and impartial investigations (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary of Scotland, 2000) and that removing police from the investigative process will make those investigations less effective. Though there is little evaluative or comparative data to either validate or refute this assumption, it is true that many police investigations of complaints do produce findings that satisfy complainants (Bayley, 1991; Smith, 2004). Police and some academics argue that police investigators are necessary in order to obtain the necessary police cooperation and legitimacy in the investigative process and that only the police have the skills, knowledge and experience required to do effective investigations (Maguire and Corbett, 1991; Prenzler, 2004).However, the issue of the possibility of PIP being seen as impartial or legitimate may ultimately not rest on facts, evidence or research but on public perceptions of impartiality and accountability (Landau, 1996; Miller and Merrick, 2002; Seneviratne, 2004). As long as police are seen as the sole investigators and adjudicators of complaints, the PIP process lacks complete public credibility and legitimacy.

2.2 Is it possible for civilian investigators to provide fair and effective investigations?

The use of civilians instead of police officers in misconduct investigations is based, in part, on the argument that police investigative skills are not necessarily unique to policing and can be gained through training, education and development. In addition, civilian investigators may also bring important non-policing skills such as statistical analysis, systems design and project management to the investigative process. But even more importantly, it is argued that because civilian investigators are not police officers they are not bound by the values or interests of the police culture and are therefore more likely to provide open and impartial investigations. The civilian dimension also provides added reassurance to a sceptical public that complaint investigations will be fair and impartial and not overly sympathetic to, or influenced by, police interests (KPMG, 2000; Strudwick, 2003). While models where civilian investigation or oversight are in operation have shown mixed results, they do show that civilian investigations are possible and that civilian complaint investigations are more likely to satisfy concerns about the independence of the investigation process (Harrison and Cunneen, 2000; Prenzler and Ronken, 2001).

Counter arguments to an exclusively civilian-based investigative process come from a mix of police and academics who argue that "civilian only" investigations are undesirable for a number of reasons (Bayley, 1983; Hutchinson, 2005). Police argue that civilians do not possess, nor can they easily acquire, the necessary investigative skills and understandings that would allow them to conduct full and fair investigations (Littlejohn, 1981). Civilian investigators will be less likely to receive the level of cooperation and access necessary for full investigations as they lack even the limited legitimacy accorded police investigators (Fyfe, 1985). Some also argue that civilian control of the investigative and governance process will ultimately undermine the responsibility and capacity of police management to govern and discipline police misconduct, allowing police to allocate that responsibility to civilian authorities (Bayley, 1983; Naegle, 1967). Finally, civilian control of police investigations signals either the reluctance or inability of the police to self-regulate their own conduct and further undermines public confidence in these organizations.

2.3 Can police culture be reformed or modified to support fair and impartial complaint investigations?

There appears to be widespread consensus among police academics and policy-makers that there exist powerful and resistant police cultures that, among other things, can inhibit or prevent fair and impartial investigations by police of serious civilian complaints. As the organizational and occupational conditions that created police culture and that inform its protective and insular character have not changed, most academic arguments assume that police culture is relatively permanent and not open to serious reform or progressive development. For example, Chan's (1999) study of reform and change in Australian policing indicated that, despite a heavy administrative investment in community policing reform, these changes were ultimately undermined by a relatively inflexible and powerful occupational police culture (Skogan, 2006).

On the other hand, while the record supports the notion that the police have been consistently resistant to external civilian reform and governance, this does not necessarily mean that police culture actually condones or encourages misconduct, corruption, or excessive use of force among its members. Some would argue that this defensive response simply reflects understanding and sympathy for the risks and tensions inherent in police work and a reluctance to submit to what is perceived to be unsympathetic and uninformed external criticism. This perception combined with an externally imposed civilian review processes is seen by many police as ultimately making police work more difficult and potentially more dangerous (Liederback et al., 2007). Even police unions have begun to accept that a more open and accountable process of complaint investigation and review is inevitable, if not desirable. Experienced police academics (Bayley, 1983; Reiner, 1992) suggest that a successful external review process must understand and address legitimate police concerns and find ways to involve police in the process of review, investigation and reform. They argue that unless civilian review can create a working relationship with police that allows them to meaningfully participate in the process of self-governance, civilian models of police governance will fail.

2.4 Are complaint investigations in a civilian review process necessarily compromised by the use of active or retired police officers?

Though an operational issue, the use of police officers in various capacities in a civilian review process has become an issue for considerable discussion in the literature. The question is: Does police involvement in the investigative and governing processes necessarily compromise the independence and integrity of civilian reviews of investigations or public perceptions of impartiality? This is important because most models of police involvement in the civilian investigations and reviews utilize active (including seconded) or retired police officers for reasons already discussed (Goldsmith, 1995; Harrison and Cunneen, 2000; KPMG, 2000; and Lewis and Prenzler, 2000).

Active police officers – most independent civilian review processes rely on the secondment of serving police officers to complete the investigation phase. Active police officers bring a range of skills, experience and legal powers that are critical to a successful investigation. However, a number of critics of this model argue that the use of active or serving police officers will mean that they are constrained by shared occupational values and perspectives that invariably will inform their findings and make it unlikely they will provide a fair and impartial investigation of fellow police officers (Goldsmith, 1995; Landau, 1996; Maguire and Corbett, 1991; Perez, 2000; Strudwick, 2003). Though the actual evidence is limited on the relative or comparative effectiveness of PIP versus civilians investigating police (CIP), there appears to be general agreement in the literature that the use of active, seconded police officers should be limited or avoided where possible (Prenzler and Ronkin, 2003).

Retired police officers – in some complaint review models "retired" police officers are assigned to conduct the necessary investigation of civilian complaints. Retired police officers, especially senior officers, have valuable police experience but do not have the same degree of identification with, or susceptibility to, the pressures of the operational police culture (Herzog, 2002). In addition, many appear to have developed more professional and independent views regarding the police function allowing them to operate with a broader perspective on policing and police governance. This seems especially true of those with senior level criminal investigative experience in command positions (e.g., superintendent rank and higher). For example, Herzog's (2002) study of senior police officers found they had a much lower identification with rank and file values and were more open to accountability processes.

Arguments against the use of even retired police officers in a civilian review process suggest that inevitably these officers will remain committed to the interests and values of their previous police culture and occupation and will be unable to operate in a completely impartial or detached manner. For example, Prenzler's (2000) use of the concept of "capture theory" explains how former police may influence and capture the civilian review processes they are involved with, resulting in findings that are more favourable to police and the general police point-of-view. This is in contrast to the results that would have been provided by a civilian-only investigation. It would seem that the use of retired police officers, and the risk posed by their police experience, needs to be assessed against the advantages of that same police experience.

3. PIP Models, Types & Variables

Introduction

This discussion is an attempt to categorize and distinguish the various models and types of investigations of police misconduct and their governance and oversight context. The following five (5) PIP models are identified from a review of the literature based upon the relative autonomy of the police and/or civilians within the PIP investigative context, as well as, the nature of police or civilian participation in the governance or oversight structure.

- Investigative model – describes the nature and degree of police involvement in the investigation of complaints of police misconduct, recognizing that there are variations in the degree and nature of police involvement, as well as, the role and extent of involvement of civilians or non-police participants in the investigative process.

- Oversight model – describes the nature and structure of the process and/or organization of the adjudication, administration and processing of the investigation of allegations of police misconduct and the degree of civilian involvement in investigation and oversight.5

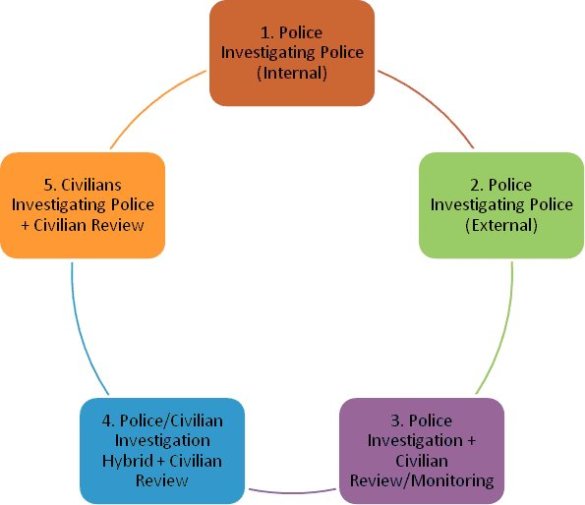

The following typology of five (5) PIP models generated from our analysis of the literature is based on the particular nature of the investigation of complaints or allegations against the police and the degree to which they are police and/or civilian-based investigations. In addition, these investigative models are distinguished by the distinctive type of oversight structure in which they operate and the nature and degree of civilian versus police involvement in the oversight process. While these models have developed during different timeframes they are all operating in various forms in Canada and internationally. From our analysis of the literature we have developed a typology of five (5) distinctive PIP investigation and review models that describe the full range of current national and international practices.

- Police Investigating Police (Inside) – this represents any investigative model where the police themselves are fully responsible for the intake, investigation, adjudication and administration of public complaints with no external civilian review or oversight;

- Police Investigating Police (Outside) – this represents any investigative model where police officers from another department or service are invited to conduct an investigation of a police service. This model of investigation is also not subject to external civilian review and oversight;

- Police Investigating Police + Civilian Review/Monitoring – this represents any investigative model where the police continue to be responsible for the intake, investigation, adjudication and administration of public complaints. There are varying degrees of civilian oversight and involvement in the PIP process, including: a) civilian review/post-investigation, and b) civilian observation and monitoring of PIP investigations;

- Police/Civilian Investigation Hybrid + Civilian Review – this represents any model where the police are engaged in some form of collaboration, cooperation or coordination of the actual investigation of public complaints. There may also be aspects where civilians are involved with the intact, adjudication and administration of public complaints; and

- Civilians Investigating Police + Civilian Review – this represents any model where the police are excluded or removed from the process of investigating public complaints. There may be some form of police involvement in the adjudication process associated with these models however the hallmark of an "independent" system will be that civilian personnel are substantially responsible for the conduct and conclusion of the actual investigation process. This model may also include some form of civilian review of any follow-up actions taken by the police service with respect to sanctions, training, education, and other organizational processes designed to address issues resulting from these investigations.

3.1 Police Investigating Police (Internal)

This model includes all PIP approaches whereby the investigation of public complaints is managed internally by police officers and the police department. Police governance of public complaints investigation and adjudication resides exclusively within the police chain of command and there is an absence of civilian review or involvement. Typically, this model is also characterized by vesting final accountability with the chief of police or chief constable and typically does not incorporate any form of external civilian review. This is the traditional form of police investigating police. An example of this would be an internal affairs investigation of a complaint with the final resolution being decided by the police chief. To reiterate, this model is in essence a process of police investigation under the governance and control of the police.

Reported Advantages

- Police have necessary investigative skills and access to appropriate resources (e.g., forensic support);

- Police understand the operating organizational and cultural dynamics;

- Police involvement guarantees legitimacy for police and will result in police cooperation (takes a police officer to catch a police officer);

- Police have the requisite legal authority and powers to complete investigations, especially regarding Criminal Code issues; and

- Police adjudication and disciplinary response is important as a way of maintaining managerial authority and responsibility within the police organization (Goldstein, 1978; Bayley, 1991).

Reported Disadvantages

- Police do not take seriously most public complaints and assign limited investigative resources and expertise to the process (KPMG, 2000);

- Police officers are sympathetic and responsive to informal police cultural norms and perspectives which protect individual officers and undermine the investigative process (Prenzler, 2000);

- Police officers can be pressured by other police and the police culture to ("blue wall" blue curtain, code of silence) conduct ineffective investigations;

- There is little evidence that police officers do actually obtain higher levels of police cooperation from other police in complaint investigations;

- Police adjudication and disciplinary processes tend not to reflect public standards and expectations regarding appropriate investigative outcomes

- Low level of substantiated complaints through this model; and

- As a result of an exclusive and compromised police involvement in all stages of the complaint and adjudication process, the model is seen by many to fail to meet the basic standards of public accountability.

3.2 Police Investigating Police (External)

This model is distinguished by its use of external police investigators from another police department to conduct a complaint investigation on behalf of the department that is the subject of the complaint. In many Canadian police services when a complaint is of sufficient magnitude they will invite another police service to take responsibility for the investigation of that complaint or allegation. This is done to enhance public perceptions of the independence of the investigation and minimizes the negative effects of internal loyalty and solidarity on the completion of a fair investigation. The involvement of external police services in a complaint may take place at various points in the investigative process. In some circumstances there are formal agreements or protocols between police organizations pertaining to the conduct of such investigations. In all cases they report their findings to the police service and do not participate in the final adjudication or resolution of the complaint. A good example of this is described in the final report of the recent Taman Inquiry.

Reported Advantages

- External police have the necessary investigative skills and police knowledge to do an effective investigation and access to appropriate resources (e.g., forensic support);

- External police have the necessary understanding of organizational and cultural dynamics required for investigations

- As police officers from another agency, they have a legitimacy within the police service which encourages cooperation and collaboration;

- External police investigation have the requisite legal authority and powers to complete investigations, especially regarding Criminal Code issues;

- As external police investigators representing another police service, they bring a measure of police independence and presumed objectivity enhancing the public legitimacy of the investigative process;

- External police investigations relieve police administrators from the pressures of conducting their own internal investigations and limits internal responsibility for any negative findings; and

- This strategy allows the police service to pursue a semi-independent police investigation without submitting to a civilian investigation and review process.

Reported Disadvantages

- Inviting an external police investigation provides only the appearance but not the reality of an independent investigation;

- Academics and critics seriously question the possibility of independence for external police investigations due to their active occupational ties and commitments (Prenzler, 2000);

- Police officers are usually sympathetic and responsive to informal police cultural norms (e.g., "blue wall," "blue curtain," or "code of silence") and perspectives which protect individual officers and undermine or influence the investigative process (Prenzler, 2000);

- There is little evidence that external police officers do actually obtain higher levels of police cooperation from other police in complaint investigations to justify their involvement;

- Without public oversight, external PIP investigations often produce similar findings to an internal investigation and result in a low level of substantiated complaints; and

- The unsatisfactory record of police investigations has diminished public confidence in the legitimacy of this alternative external model of PIP as meeting adequate standards of accountability.

3.3 Police Investigating Police + Civilian Review & Civilian Observation

This model reflects many of the same features as the two previous PIP models in that it is a police managed investigative process. However the outcomes of the investigation are reviewed by some form of external, civilian review agency or agent. This review of the investigative process is either a post-investigation civilian assessment or some form of civilian monitoring/observation of the criminal investigation process. The PIP plus post-investigation civilian review is limited to after-the-fact assessments of the investigative process and has no direct influence on the investigation process. The PIP plus civilian monitoring/observation variation suggests a more active and engaged role for civilian oversight and direct influence in the investigative process. It is generally regarded as a more effective form than the investigative oversight model. A good example of the PIP plus civilian review is to be found in the work of the British Columbia Public Complaints Commissioner. An example of the PIP plus civilian monitoring/observation approach is exemplified in the work of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP. The reported advantages and disadvantages outlined below are generic and apply equally to civilian review and monitoring/observation approaches.

Reported Advantages

- Introduces a civilian or non-police influence, enhancing public accountability in an otherwise internal police-centric public complaints process;

- Civilian review and/or observation provides an opportunity to monitor the adequacy and effectiveness of police complaint investigations and make recommendations to either a police or civilian authority regarding appropriate findings and sanctions;

- Civilian review and/or observation of PIP can provide an opportunity for independent assessment and review of general police management and operational practices that contribute to complaint issues; and

- Civilian review and/or observation of police investigating police provides a level of transparency and public information to an otherwise internal and closed process.

Reported Disadvantages

- Civilian review and/or observation of a police-centric investigative process cannot fully address public concerns about the independence and adequacy of PIP investigations;

- Civilian review and/or observation agents or agencies tend not to have the authority, resources or powers to adequately insure that PIP investigations meet the standards of public accountability;

- Civilian review and/or observation agents or agencies cannot conduct their own investigations and are therefore entirely dependent upon PIP in the first instance;

- Civilian review and/or observation of PIP is based upon an insufficient and limited understanding of police administration and operations which minimizes their efficacy;

- Civilian review and/or observation of PIP is viewed as illegitimate and inappropriate by some police officers and associations) as unqualified, unsympathetic and incompetent;

- Civilian review and/or observation is viewed as costly, ineffective and time-consuming; poor value for money; and

- Despite civilian involvement in the review of PIP some critics argue it has not created an increase in sustained complaints and publicly satisfactory outcomes.

3.4 Police/Civilian Investigation Hybrid + Civilian Review

This model is distinguished by the involvement of civilian investigators in the investigative process of police complaints in some relationship with police investigators. This could include a collaborative effort between civilian and police investigators or civilians alone conducting complaint investigations. Direct involvement of civilians in the investigative process and either civilian or police management of the investigation of complaints usually operate under the general authority of some form of civilian oversight or review. An example of the first variation is the Chicago Police Department. An example of the second approach is the Alberta Special Investigative Response Team (ASIRT) which employs a combination of civilian and seconded police investigators.

Reported Advantages

- Retaining experienced police involvement in the investigative process whether under the direction or in coordination with civilian agents will provide balanced and ultimately more effective outcomes to the complaints process;

- Seconded officers retain essential police powers for the conduct of criminal investigations which their civilian counterparts do not normally possess;

- Seconded or retired police officers bring an understanding of the police organization and culture which may produce a more cooperative investigative environment;

- Seconded/retired officers would have some special investigative skills and aptitudes which civilian investigators are unlikely to possess; and

- Synergy between the different skills and experience of civilian and police investigators lead to an overall enhancement of the complaints investigation process.

Reported Disadvantages

- This hybrid model still fails the public test of full accountability and independence;

- Police involvement may undermine the independence of civilian oversight and may ultimately make it less effective in meetings its accountability objectives;

- The introduction of police culture and police values through the ongoing involvement of retired or seconded police may inhibit the development of a new civilian organizational culture; and

- It may be difficult to either second or attract experienced senior police investigators to a hybrid model in which they do not have authority or control.

3.5 Civilians Investigating Police + Civilian Review

This model is distinguished by its exclusive reliance on civilians to conduct all phases of the complaints process, including investigations and outcome recommendations. This PIP model could include retired police officers who no longer possess their original police powers, or, civilians who have had no previous police experience. This model is considered to be the most distinctive "alternative" form of PIP as it gives police no formal power or influence in the complaint and review process. An example of this model may be found in the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland (PONI).

Reported Advantages

- This model would be regarded by most members of the public as the most independent of the five investigative models;

- Because of the absence of police experience and influence/culture a more accountable organizational culture will inform the investigative process;

- Complainants will have more confidence in and will cooperate more freely with non-police investigators; and

- In some circumstances the independence of the civilian investigative process would provide police with a stronger public validation of their position.

Reported Disadvantages

- Lacks police experience, expertise, knowledge and understanding which some argue are required to do fair and effective investigations;

- A civilian only investigative/adjudication process will be perceived by most police as being inadequate and unsympathetic to police concerns and their operational realities;

- This lack of police legitimacy will more likely diminish police cooperation and participation ultimately leading to unsuccessful and failed investigations;

- Disappointed by unsuccessful and failed investigations members of the public will lose confidence in the fully independent civilian review model;

- Consultants argue that this is the most expensive model as it requires additional resources to ensure professional investigations (i.e., forensic services, etc.);

- Higher training costs for skill development, enhancement and ongoing education;

- Civilian models require special legal and investigative powers in order to deal adequately with serious investigations; and

- This model would undermine the authority and responsibility of police management with regard to a spectrum of operational and administrative processes.

3.6 Typology of Public Complaints Investigations & Oversight Models

The following graphic provides a visual summary of the five (5) models discussed. This typology of public complaints investigations is extended in the subsequent section of this report which contains a more detailed outline of the police complaints investigations and oversight models that exemplify each of the models. This typology attempts to provide some further insight into the distinctive elements that inform each of the various PIP models described. The outline includes information pertaining to particular oversight bodies, their legislative authority, jurisdiction, reporting relationship and year of formation. These five (5) models are intended to contextualize and situate the concept of police investigating police.

Typology of Public Complaints Investigations & Oversight Models

| Oversight Body (Location) | Legal Authority | Jurisdiction* | Reports To | Year Formed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Police Investigating Police (Internal) | ||||

| Office of Professional Responsibility (United States) | Title 28, Section 533, US Code | Federal Bureau of Investigation agents | Department of Justice | Not reported |

| Internal (Netherlands) | Police Act | All Dutch police | Minister of Interior & Minister of Justice |

Not reported |

| 2. Police Investigating Police (External) | ||||

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | RCMP Act | Any police service with formal or informal agreement or protocol providing for external investigations. Example: RCMP was requested to investigate the Toronto Police Service in 2003 | RCMP Commissioner | 1920 |

| Ottawa Police Service | Police Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.15 | Police service with formal or informal agreements providing for external investigations6 | Chief of Police | 1855 |

| 3. Police Investigating Police + Civilian Review/Observation | ||||

| Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (Canada) | RCMP Act, Section 37 | All RCMP officers | Public Safety Minister | 1987 |

| Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner (British Columbia) | Part 9, Police Act, RSBC, 1996, c.367 | All British Columbia police* | British Columbia Legislature | 1998 |

| Law Enforcement Review Agency (LERA) (Manitoba) | Law Enforcement Review Act, CCSM, c.L75 | All Manitoba police officer * | Annual report to the Minister of Justice; administratively to the ADM, Criminal Justice | 1985 |

| Ontario Civilian Commission on Police Services7 (OCCPS) | Police Services Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.15 | All Ontario police* | Ontario Minister of Public Safety and Correctional Services | 1990 |

| 4. Police/Civilian Investigation Hybrid + Civilian Review | ||||

| Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT)8 (Alberta) |

Police Act | All Alberta municipal police* | Alberta Solicitor General and Public Security Minister | 2007 |

| Public Complaints Commission (PCC)9 (Saskatchewan) |

Police Act, 1990 | All municipal police in the province* | Saskatchewan Deputy Minister of Justice | 1990 |

| Crime & Misconduct Commission10 (Australia) |

Criminal Justice Act, 1989; Crime & Misconduct Act, 2001 | All "units of public administration" in Queensland, including police services | Parliamentary Crime & Misconduct Committee | 2002 |

| Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC)11 (Great Britain) |

Police Reform Act, 2002 (c. 30); Police and Justice Act, 2006, s. 41 | All police officers in England & Wales | Home Secretary | 200412 |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB)13 (New York City) | City Ordinance | All NYPD officers14 | Mayor | 1993 |

| 5. Civilians Investigating Police + Civilian Review | ||||

| Special Investigations Unit (SIU)15; Independent Police Review Directorate [pending formation]16 (Ontario) |

Part VII, s. 113 Police Services Act; Bill 103 |

All Ontario police officers* | Attorney General of Ontario | 1990 2008 [director appointed] |

| Police Ombudsman of Northern Ireland17 (Northern Ireland) |

Police (Northern Ireland) Act, 1998; 2003 | All Northern Ireland Police | Secretary of State | 2001 |

| Independent Police Review Authority18 (Chicago) | City Ordinance | All Chicago Police Department officers | Chicago City Council | 2007 |

* Indicates Canadian jurisdictions where the public complaints authority has no jurisdiction over RCMP officers.

4. Knowledge & Research Gaps

Despite the growing importance of, and controversy over, PIP and civilian oversight our review of the literature reveals little direct research of any kind on the actual operations and activities of the various models of PIP, let alone research that meets conventional social science and academic standards. To be more specific, there are a number of research and knowledge areas that need various kinds of study in order to understand and evaluate the relative effectiveness of the several models under consideration. Most of the PIP research is conducted at a general, descriptive level and is short on empirical data and long on prescriptive advice (Walker, 2007). There appears to be so little empirically-based knowledge on PIP that it is impossible to answer with any certainty even the most fundamental questions about PIP investigations, let alone identify with any confidence best practices. For example, we have no reliable data from which to draw comparisons with regard to the relative effectiveness of police investigations or results or to explain why this is the case. Our review of the academic literature suggests that for academics and most policy-makers PIP and its variations exist as a virtual 'black box' in which the dynamics and details of the investigative process remain unknown and unclear and only outcomes have any visibility. The following are some of the more obvious PIP research gaps that we believe should be part of a policy research agenda. To provide some insight on future directions regarding PIP and related topics, this section will enumerate specific research gaps and provide appropriate research suggestions aimed at closing those gaps. While by no means exhaustive, we have endeavoured to encapsulate the most significant areas where further study is warranted.

4.1 Research Gap – Quality of Investigations

There appears to be virtually no case studies of actual investigations of various kinds of PIP, or other related, processes that would allow detailed analysis leading to the establishment of good practice and to assist in discerning bad practice. Furthermore, there is a lack of detailed empirical data and information on PIP and its variations of either a qualitative or quantitative nature. This means that it is difficult to say with any certainty whether one model is more effective than another and why that is the case.

Research Suggestion – PIP Case Studies

Research that can document in detail the investigative dynamics and strategies used in the various factors that affect investigative outcomes would allow for an assessment of the relative merits of different models and some systematic comparative analysis. This would be helpful in providing some empirical basis or evidence about the efficacy of one or another of the PIP models or structures.

4.2 Research Gap – Unclear Investigative Skills

Though civilian investigators or investigations are argued by some to be a more desirable substitute for PIP approaches, there is currently no available evidence or research to either support this assertion or clarify the necessary investigative skills required for this function. Reliance on civilian investigations should be based on evidence that this is a valid hypothesis.

Research Suggestion – Identification of Investigative Skills

Develop a research focus that would lead to an articulation of the necessary skills and experience to do effective internal police investigations and provide an assessment on how best to transfer this functional knowledge for use by civilian investigators. Conduct an examination of the investigative and analytic skills that may be required. Research and report on the functional skill assessment and competency profile for investigators.

4.3 Research Gap – Uncertain Impact of Police Culture(s)

While police culture has been blamed for many of the problems encountered in PIP or alternative models, there is relatively little detailed research that specifically describes and analyzes the role of police culture in the investigation of complaints against the police (Skolnick, 2006). Given the alleged persistence and significance of police culture in rationalizing and protecting some questionable police activities, it would be useful to have more modern ethnographies on the contemporary nature and function of culture in modern police organizations. Such studies should also explore persistent police concerns about the impact and effect of civilian investigations and oversight of their work (Bayley, 1983).

Research Suggestion – Determining Impact of Police Culture(s)

More ethnographic work and field studies that focus on a contemporary understanding of modern police organizational and cultural dynamics and the function of police resistance to external review might be helpful in the development of models that could enhance police cooperation and collaboration within various external review systems.

4.4 Research Gap – Lack of Systematic Focus

With the exception of work by Janet Chan (1999), and some more general British police studies, there has been little attempt to examine new models of police management and the various technologies being employed to manage and document police activity and behaviour. Risk management models and tactics, or the "new accountability" (Chan, 1999) are supposed to diminish instances of police deviancy or mistake. Civilian review agencies need to develop ongoing monitoring and accountability mechanisms, in combination with the capacity to assess the impact of structural and procedural change. Such new management strategies as quality assurance, continuous improvement, organizational learning (Goldsmith and Lewis, 2000), the balanced scorecard, and organizational alignment offer, at least in theory, better management through more indirect forms of guidance and control.

Research Suggestion – Continuous Improvement Research

Conduct research that provides a forum for a collaborative approach to continuous improvement within existing systems of public complaints intake, investigation and adjudication. This could include the collection and analysis of complaints data and management information with regard to investigations that would form the basis for the establishment of performance measurement goals and objectives. Research that will consolidate and facilitate the management of institutional knowledge will be beneficial to individual public complaints agencies but will also contribute to a broader understanding of police complaints and oversight systems generally. Among the topics that would be consistent with a continuous improvement model of research would be the following:

- Public and police levels of satisfaction with public complaints system processes and approaches;

- Indicators of volumes of complaints dealt with in various stages (e.g., investigations, supervision of investigations, investigation plans);

- Completion times for specific stages within the complaints process;

- Numbers of investigations combined with disciplinary outcomes;

- Numbers of interventions through supervision or monitoring of police investigations; and

- Costs of investigations and other stages in the complaints process.

4.5 Research Gap – Police Association Opposition

There is little research that adequately explores the role of police associations and collective bargaining agreements in inhibiting or assisting PIP or alternative investigations (Walker, 2006). Police associations in Canada are little studied and yet they play a pivotal role in policy-making, procedure formulation and legislative reform impacting on public safety.

Research Suggestion – Examination of Police Association Engagement/Disengagement

Conduct research that will examine the role of police associations in the context of PIP and its alternatives. This research could include an analysis of police associations at national, provincial, and municipal levels with regard to the reform of public complaints systems.

4.6 Research Gap – Uncertain Public Legitimacy

We lack precise knowledge about how various elements or aspects of PIP, or alternative models, can contribute to, or undermine, the public legitimacy of the civilian oversight/review process (e.g., the seniority of police officers involved, communications, and the status of the civilian overseer, among others). A hallmark in the reform of police complaints systems has been the overarching requirement for public legitimacy with respect to the processes, practices, and most particularly the people engaged in these systems. Research that would explore this dimension in a clear, consistent and comprehensive manner would benefit our understanding of the Canadian experience with public complaints.

Research Suggestion – Exploration of Public Uptake & Support

The design and completion of research that would consider particular aspects of PIP and alternative models as they relate to public acceptance would be valuable for future reforms and overall policy development. The success and effectiveness of any police complaints system rests extensively upon public acceptance. The credibility of a police complaints system must certainly meet important criteria set by police leaders, police associations and front-line officers. However, the public uptake of and support for these systems is contingent upon a better understanding of the precise elements that will contribute to accessible, accountable, fair, independent, and transparent principles and practice.

4.7 Research Comment – PIP & General Police Knowledge Generation & Research Support

Advocating for more research is a predicable academic response to almost any problem, but this review makes it clear that PIP, and its alternatives, clearly lack adequate academic or policy research. The annotated bibliography identifies relatively few research-based articles or reports directly grounded on an analysis of PIP investigations. This is surprising given the importance of PIP and is underscored by the fact that this is the first research document which actually attempts to collect and analyze the available academic and policy information on this critical issue. This lack of PIP research in Canada is not surprising when placed in the larger context of limited and fragmented police research on virtually all policing issues; especially applied policing issues. The lack of any centre for social science police research in Canada, and a lack of government, private sector or police research support mean that most Canadian policing and policy issues are not based upon research evidence, evaluation or even ongoing monitoring. That there is little empirical work available, either on PIP or its alternatives is therefore not surprising, as it is unclear who would fund or do such research.

PIP research has the additional problem that it, like so many policing issues, is a controversial public and political issue. Thus research by either the police or civilian review agencies will be seen as partisan and, therefore, unreliable. What is ideally required is adequate funding for independent research agencies or organizations, such as the British Police Foundation, that have responsibility for, and a capacity to undertake, independent research on policing issues such as PIP. In addition, police agencies like the RCMP, which adopt policies and strategies that make various assumptions, need to be able to demonstrate that their policies and practice are based on reasonable and ongoing research evidence. This is not a common phenomenon within police agencies in Canada, but we suggest that its absence leads to poor policing policy and ineffective practice. Furthermore, police, external review agencies and government bodies need to have the resources and capacity to go beyond simple case investigations and review in order to conduct the kind of research required to proactively identify the causes of problems and explore alternative models and practices. This PIP research project is an example of the kind of knowledge development that can lead to constructive debate and policy development.

5. Conclusion

This review of the academic and policy literature on the issue of police investigating police (PIP) in a governance context, suggests a number of conclusions. Notwithstanding the lack of empirically based studies on the dynamics and problems of PIP investigations and its civilian alternatives, there does appear to be an emerging consensus in the literature that traditional models of PIP are no longer seen as defensible, either as an effective model for addressing public complaints or as a method satisfying public demands for accountability. However despite consensus on the limits of the traditional PIP model there is less agreement on its civilian alternatives.