Report Following a Chair-Initiated Complaint and Public Interest Investigation into the In-Custody Death of Clay Willey

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act Subsections 45.37(1) and 45.43(1)

January 31, 2012

File No.: PC-2009-3397

Table of Content

- Introduction

- The Chair-Initiated Complaint and Public Interest Investigation

- Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

- Analysis – Compliance with Policies, Procedures, Guidelines and Statutory Requirements

- Analysis – Adequacy of the Investigation

- Analysis – Integrity of the Video Evidence

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Summary of Findings and Recommendations

- RCMP Members Involved in the In-Custody Death of Clay Willey and Subsequent Investigation

- Chair-Initiated Complaint & Public Interest Investigation – In-Custody Deaths Proximal to CEW Use

- Correspondence from the BC Solicitor General

- Amendment to Chair-Initiated Complaint & Public Interest Investigation – In-Custody Deaths Proximal to CEW Use

- Canada Criminal Code Provisions

- Incident Management / Intervention Model Graphical Depiction

- Categories of Resistance of Individuals

- Investigation Timeline

Introduction

On July 21, 2003, Mr. Clay Alvin Willey was arrested by members of the Prince George, British Columbia, RCMP Detachment. Shortly after being taken to the detachment, a decision was made to transport Mr. Willey to the hospital. Mr. Willey went into cardiac arrest in the ambulance and died the following morning. The death of a person following an intervention by police often raises questions from the public about the use of force involved, the training of officers, the appropriateness of the police investigating the police and the expected level of transparency of authorities.

In recognition of the concerns expressed about the use of force by RCMP members, the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (the Commission) will on occasion exercise its authority on behalf of the public, to examine in depth the facts that give rise to the public's concern as well as the adequacy of the RCMP's investigation of the events in question. This report examines the circumstances of Mr. Willey's arrest and subsequent death. It will focus particularly on the events leading to the altercation with Mr. Willey, the level of force used to subdue him, the actions of the RCMP members involved in the altercation and arrest, the following investigation, its adequacy and timeliness and the RCMP policies and procedures underlying this event.

On January 15, 2009, the then Chair also initiated a complaint into the conduct of those unidentified RCMP members present at, or engaged in, incidents where individuals in the custody of the RCMP died following the use of a conducted energy weapon (CEW), which incidents have taken place anywhere in Canada between January 1, 2001 and January 1, 2009. The arrest and subsequent death of Mr. Willey was also considered in that report, which was provided to the RCMP Commissioner in July 2010.

OverviewFootnote 1

On Monday, July 21, 2003, members of the Prince George RCMP Detachment were sent to the area of 11th Avenue in response to two 911 calls. Four units attended. One of the complainants reported a man with a knife and indicated that this man had threatened his dog. On arrival, officers were directed to the rear alley of the Parkwood Mall in the vicinity of the parkade. There, officers found Clay Alvin Willey.

Mr. Willey was found behaving aggressively toward a mall security guard. He was confronted by officers, but did not respond to their verbal commands. He was not armed. Mr. Willey was taken to the ground and a violent struggle ensued. It took three officers to subdue Mr. Willey. He apparently demonstrated incredible strength and seemed oblivious to pain control techniques. Officers believed Mr. Willey to be in a drug-induced state. During the arrest he was pepper-sprayed, punched twice and kicked twice before the handcuffs could be applied. Even in handcuffs, the struggle continued, leaving members with the need to bind his legs. The only device available to them was a hog-tie rope, the use of which had been discontinued by the RCMP. The senior member at the scene made the decision, for safety reasons, to apply the hog-tie. A decision was also made to take Mr. Willey to cells rather than to the hospital at that time.

Mr. Willey was then transported to the cell block at the Prince George RCMP Detachment. On arrival, he was dealt with by three officers who had not been involved in the arrest. Mr. Willey was pulled by his feet out of the back seat of a police vehicle. Mr. Willey continued to strain against his bindings. He was dragged face down across the concrete floor and down a hallway to the elevator door. When the three officers filed their written reports, they described their actions as having carried Mr. Willey to the elevator by holding his upper torso up off of the ground; video evidence later revealed that that was not the case.

On arrival at the second floor, Mr. Willey was dragged face down out of the elevator and left on the floor. He continued to strain against his bindings, but remained handcuffed and hog-tied. Officers spoke to Mr. Willey, apparently in an attempt to calm him down and have him stop straining against the handcuffs and hog-tie, as he could not be placed in cells while demonstrating that behaviour. An ambulance was called with the intention of having paramedics administer a sedative. Before the ambulance arrived, two officers simultaneously activated their conducted energy weaponsFootnote 2 (CEW), and used them on Mr. Willey in the touch stun mode in an effort to reorient him. The CEWs did not have the desired effect and Mr. Willey continued to struggle against his bindings as he lay on the floor.

Shortly thereafter, the ambulance attendants arrived but were unable to sedate Mr. Willey. The decision was made to take Mr. Willey to the hospital. While in transit, he suffered the first of several cardiac arrests. Mr. Willey died the following morning.

The Chair-Initiated Complaint and Public Interest Investigation

On January 15, 2009, the Chair of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP initiated a complaint and a public interest investigationFootnote 3 (pursuant to subsections 45.37(1) and 45.43(1) of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act – RCMP Act) into the conduct of those unidentified RCMP members present at, or engaged in, incidents where individuals in the custody of the RCMP died following the use of a conducted energy weapon (CEW), which incidents have taken place anywhere in Canada between January 1, 2001 and January 1, 2009.

The arrest and subsequent death of Mr. Clay Alvin Willey in Prince George, British Columbia, on July 22, 2003 is one of the incidents covered by that complaint. The original complaint was initiated to examine:

- whether the RCMP officers involved in the aforementioned events, from the moment of initial contact with the individual until the time of each individual's death, complied with all appropriate training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements relating to the use of force; and

- whether existing RCMP policies, procedures and guidelines applicable to such incidents are adequate.

Mr. Willey's death was the subject of a coroner's inquest conducted by the British Columbia Coroner's Service in October 2004. One of the pieces of evidence considered at the coroner's inquest was a compilation of video footage from a number of security cameras located throughout the Prince George RCMP Detachment. Subsequent to the launch of the Chair's complaint and public interest investigation, the Solicitor General of British Columbia, on behalf of the residents of British Columbia, raised concerns directly with the Chair regarding this incident and in particular with respect to the integrity of the video evidence relating to the arrest and detention of Mr. Willey.

In correspondence to the Commission,Footnote 4 the Solicitor General commented that members of the media have "raised concerns with the in-custody treatment of Mr. Willey and have expressed concern that the video in question has not been released to the public. Allegations have also been made in the media that further video evidence exists beyond that contained in the compilation video." Consequently, the Solicitor General requested that the Commission "review the circumstances surrounding the death of Mr. Willey so that British Columbians can have continued confidence in the RCMP."

As such and without limiting the generality of the foregoing, the Chair expanded the public complaint and public interest investigationFootnote 5 to examine:

- 3. whether the RCMP members involved in the investigation of Mr. Willey's arrest and subsequent death conducted an investigation that was adequate, and free of actual or perceived conflict of interest; and

- 4. whether any other video evidence (other than the compilation video referred to above) exists and whether any RCMP member concealed, tampered with or otherwise inappropriately modified in any way, any evidence, in particular any video evidence, relating to the arrest of Mr. Willey.

Pursuant to subsection 45.43(3) of the RCMP Act, I am required to prepare a written report setting out my findings and recommendations with respect to the complaint. This report constitutes my investigation into the issues raised in the complaint, and the associated findings and recommendations. A summary of my findings and recommendations can be found in Appendix A.

Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

It is important to note that the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP is an agency of the federal government, distinct and independent from the RCMP. When conducting a public interest investigation, the Commission does not act as an advocate either for the complainant or for RCMP members. As Chair of the Commission, my role is to reach conclusions after an objective examination of the evidence and, where judged appropriate, to make recommendations that focus on steps that the RCMP can take to improve or correct conduct by RCMP members. In addition, one of the primary objectives of the Commission is to ensure the impartiality and integrity of RCMP investigations involving its members.

My findings, as detailed below, are based on a careful examination of the extensive investigation materials, the RCMP's criminal investigation report, and the applicable law and RCMP policy. It is important to note that the findings and recommendations made by the Commission are not criminal in nature, nor are they intended to convey any aspect of criminal culpability. A public complaint involving the use of force is part of the quasi-judicial process, which weighs evidence on a balance of probabilities. Although some terms used in this report may concurrently be used in the criminal context, such language is not intended to include any of the requirements of the criminal law with respect to guilt, innocence or the standard of proof.

A coroner's inquest into the death of Mr. Willey was held in Prince George, British Columbia, in October 2004. The purpose of such an inquest is to ascertain how, when, where and by what means the deceased died. Although the mandate of an inquest is quite limited, I considered the evidence heard to be an important part of the fact-finding process related to Mr. Willey's death. It is for this reason that the Commission has reviewed all of the testimony given during the inquest.

It should be noted that the RCMP's "E" Division provided complete cooperation to the Commission throughout the Chair-initiated complaint and public interest investigation process. In addition, the RCMP provided the Commission with unfettered access to all materials contained in the original investigative file and all materials identified as part of the public interest investigation. Unless otherwise noted, the members named in this report are referred to by their rank at the time this incident occurred.

FIRST ISSUE: Whether the RCMP officers involved in the aforementioned events, from the moment of initial contact with Mr. Willey until the time of his death, complied with all appropriate training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements relating to the use of force, and whether existing policies, procedures and guidelines are adequate.

The events of July 21, 2003

The following account of events flows from witness statements provided during the initial police investigation. I put these facts forward, as they are either undisputed or because, on the preponderance of evidence, I accept them as a reliable version of what transpired.

a. The 911 Calls

On Monday, July 21, 2003, shortly after 5 p.m., the Prince George RCMP Detachment began to receive calls about a man causing a disturbance in the vicinity of 11th Avenue. It was initially reported to police that the man was acting erratically and had threatened a dog with a knife. Several witnesses reported seeing a man, later identified as Clay Alvin Willey, in a neighbourhood located near the Parkwood Mall.

A resident of 11th Avenue was riding his bicycle home when he saw Mr. Willey running "at a full gallop" along the roadway as though he was being pursued. He described Mr. Willey as "moaning and groaning and flailing his arms". The resident saw Mr. Willey suddenly drop to his knees and look under a parked vehicle, and then jump to his feet and run across the street. He described Mr. Willey as being "very distressed."

At about the same time, another resident of 11th Avenue was in her front yard with one of her children. She first noticed Mr. Willey blocking traffic by lying on the roadway. Initially, she thought it was a "drunk" from the Bus Depot and sent her son inside the house. By the man's conduct, she recognized that "there was obviously something wrong with him." She reported that she saw Mr. Willey run as fast as he possibly could through a grouping of trees and run headlong into a fence. Mr. Willey came flying out backwards and landed on the ground. At that point, she recognized the man as being Clay Willey. She last saw him running down 11th Avenue towards Winnipeg Street.

A third resident of 11th Avenue made a phone call to 911 at the request of her boyfriend. According to the transcript of the 911 call, she reported the following:

There is a gentleman in front of my place turning around, rolling around on the grass. He's broken my neighbour's tree. We're not sure if he's under the influence of drugs or alcohol, but he's not in his right mind.

Two minutes later, at approximately 5:14 p.m., a second 911 call was received from Mr. Neil Fawcett, who resided on the south side of 11th Avenue, backing onto Parkwood Mall. Mr. Fawcett reported that he had returned home from work shortly after 5 p.m. On arrival, he heard his dogs barking in his rear yard. When he went out to his rear yard, he saw Mr. Willey in the next-door neighbour's yard. Mr. Fawcett reported seeing Mr. Willey making repeated runs at the neighbour's cherry tree in an apparent attempt to climb the tree. In a statement to police shortly after the incident, Mr. Fawcett reported that he saw Mr. Willey "holding his head and rolling, standing up, laying down, standing up, laying down, rolling around, holding the back of his head."

Mr. Fawcett's first impression was that Mr. Willey was suffering a seizure akin to an epileptic fit. Mr. Fawcett reported that Mr. Willey "charged the fence" and pulled something out of his pocket that Mr. Fawcett took to be a knife. (That object was later identified as a cell phone.)

Mr. Fawcett was concerned that, because of the barking of the dogs, Mr. Willey was intent on attacking them. Mr. Willey came over the fence into Mr. Fawcett's yard. After crossing the fence, Mr. Willey took hold of the top rail of the fence and tore it off. At that point, Mr. Fawcett stepped between Mr. Willey and the dogs. Mr. Fawcett could see a red mark on the back of Mr. Willey's head and thought that perhaps he had received a blow to the head. Mr. Fawcett went into his house to call 911.

Mr. Fawcett reported that Mr. Willey never spoke coherently until he picked up one of the dogs and remarked that he loved dogs. That was the only comment Mr. Fawcett could understand and it was recorded as part of the 911 conversation.

Patrol officers were dispatched to 11th Avenue at 17:16:50 hours. According to the transcript of the Communications Centre tape, responding officers were provided with the following information:

[...] do I have anyone available for a disturbance, we have a Caucasian male in his twenties, he's wearing a blue football jersey with the words "BRADY" on the back, he's outside of 1688 – 11th Avenue, running around rolling on the lawn, he's damaged a neighbour's tree and now he is outside of 1775 – 11th Avenue and he has a knife, he's threatening a dog.

Constable John Graham in Unit 13B1, Constable Holly Fowler in Unit 13B16, Constable Kevin Rutten in Unit 13B13 and Constable Lisa MacKenzie in Unit 13B6 all responded to the call.

b. The RCMP's Initial Response

The first officers on scene went to the residence of the first 911 caller. They were advised that Mr. Willey was not there. They next went to Mr. Fawcett's residence. Constables Rutten and Graham accompanied Mr. Fawcett into his backyard. Mr. Fawcett explained the situation to Constable Rutten and told him that the man had dropped the knife and fled. Constable Graham overheard the conversation and looked to where Mr. Fawcett had pointed. Constable Graham reported that he saw a cell phone on the ground, not a knife. By that point, Mr. Willey was gone and a neighbour, seeing the police officers in the backyard, called to them to say that Mr. Willey had gone into the parkade. Constable Graham used his radio to transmit that information to other responding officers. He then went back to his police cruiser and drove to the entrance to the parkade.

Once inside the parkade, Mr. Willey was heard banging on the window of a vehicle parked there. Brian Chadwick, a security guard working for the Parkwood Mall, reported that he was working in his office when he heard a noise that caught his attention. He left his office to investigate and noticed Mr. Willey lying on his back on the ground in the parkade. Mr. Chadwick described Mr. Willey as holding his head and rolling around on the ground. Mr. Chadwick reported that Mr. Willey was wearing only one shoe at that point and had blood underneath his nose and on the right side of his head. Mr. Chadwick approached Mr. Willey and asked what he was doing. Mr. Willey then jumped up and lunged at Mr. Chadwick. Mr. Chadwick backed away and was in the process of dialling 911 on his cell phone when Constable Holly Fowler (now Corporal Holly Hearn) arrived on scene in a marked police cruiser.

Constable Fowler parked her cruiser at the entrance to the parkade and got out of her vehicle at approximately 5:20 p.m. She was in full police uniform. Upon her arrival, Constable Fowler saw Mr. Willey and Mr. Chadwick in the parkade.

c. The Arrest and Use of Force

Constable Fowler saw Mr. Willey, whom she had known for some twenty years, move towards Mr. Chadwick in what she described as a threatening manner. Mr. Willey fell back to the ground. He then began rolling on the ground, kicking his legs and swinging his arms. After only a few seconds, Mr. Willey got to his feet and began walking towards Constable Fowler. She yelled, "Clay get down on the ground, get down," but Mr. Willey continued moving towards her. She interpreted his actions as a threat towards her and drew her oleoresin capsicum (OC) spray (commonly known as pepper spray). As Mr. Willey advanced towards her, Constable Fowler began backing up to try and maintain a safe distance between them. However, Mr. Willey walked faster towards her.

At this point, Constable Fowler noticed that Mr. Willey was bleeding from the mouth. The injury appeared to be fresh. Constable Fowler repeated her instructions to Mr. Willey but he did not respond to her commands and continued to advance. Her initial assessment of Mr. Willey led her to believe that he was on drugs. With his history of drug abuse and the information that he may have been in possession of a knife, Constable Fowler formed the opinion that Mr. Willey posed a threat to both her and the security guard. She intended to use her OC spray against him when Constable Graham ran up beside her.

As Constable Graham approached, he noticed that Mr. Willey had blood coming from his mouth as well as a "foamy substance on his lips." Constable Graham, who is senior in service to Constable Fowler, took command of the situation and intended to arrest Mr. Willey for causing a disturbance. As he ran up to the right of Constable Fowler, Constable Graham noted that he was able to see Mr. Willey's left hand, which was clenched in a fist. Constable Graham could not see Mr. Willey's right hand. At that point, Mr. Willey was unresponsive to the commands issued by Constable Fowler. Constable Graham, concerned by the possibility that Mr. Willey may have a knife, drew his service pistol and pointed it at Mr. Willey while commanding him to show his hands.

Constable Graham was finally able to see both of Mr. Willey's hands and determined that he did not have a weapon in either, so he holstered his pistol. He directed Mr. Willey to get down on the ground, but Mr. Willey was unresponsive and continued to advance. Constable Graham described Mr. Willey's behaviour as "combative" and knew he could have resorted to OC spray or his baton to control Mr. Willey. However, Constable Graham decided against either of those options because he believed he was physically capable of controlling Mr. Willey. Constable Graham then took hold of Mr. Willey's left arm in an arm bar hold and forced Mr. Willey to the ground. As Constable Graham later explained, he had to use a "great deal" of force to take down Mr. Willey. Once he was on the ground, Mr. Willey began kicking his legs. Constable Graham attempted to control Mr. Willey's left arm by using a wrist lock. However, Constable Graham was surprised by the strength demonstrated by Mr. Willey, who was able to pull his left arm free. Constable Graham described the strength of Mr. Willey as "superhuman."

Constable Rutten had followed Constable Graham from the residence of Neil Fawcett and parked his police vehicle in the vicinity of the other cruisers near the entrance to the parkade. He exited his vehicle and came to the assistance of Constable Graham who was already on the ground struggling to control Mr. Willey. Constable Rutten believed Mr. Willey to be in a rage or "high on some sort of drug." Constable Graham reported that he knew Mr. Willey had a history of intravenous drug abuse and, because of the presence of blood and bodily fluids, Constable Graham was concerned for his personal safety and that of the officers assisting him.

Constable Rutten took hold of Mr. Willey's right arm in an attempt to force it behind his back so that handcuffs could be applied. Mr. Willey resisted those efforts and attempted to pull his arms free from the grasp of the officers. Constable Rutten was also surprised by the strength demonstrated by Mr. Willey and by the fact that Mr. Willey gave no indication of tiring during the struggle. Constable Rutten managed to apply a handcuff to one of Mr. Willey's wrists, but was unable to force Mr. Willey's arm behind his back so that his other wrist could be handcuffed. Constable Rutten issued commands to Mr. Willey to stop resisting, but the struggle continued.

Constable Rutten reported that he was concerned that he was going to lose his grip on Mr. Willey's arm. That would have turned the handcuff around Mr. Willey's wrist into a weapon if he swung it at the officers. Constable Rutten reported that he therefore felt he needed to escalate the level of force he was using. Constable Rutten maintained control of Mr. Willey's arm and kicked Mr. Willey twice; landing blows in the area of Mr. Willey's upper chest. This use of force produced no change in the resistance offered by Mr. Willey.

When the kicks produced no change in behaviour on the part of Mr. Willey, Constable Rutten then resorted to his OC spray. Constable Rutten reported that he sprayed approximately one quarter canister of OC spray directly into the centre of Mr. Willey's face from a distance of about twelve inches. As the OC spray did not have the desired effect on Mr. Willey, there was no noticeable change in the resistance offered by him.

Constable Fowler, operating under instruction from Constable Graham, also assisted in attempting to apply the handcuffs to Mr. Willey. Mr. Willey demonstrated remarkable strength in rising onto his knees despite being held by the police officers. Constable Graham considered and discounted the use of OC spray because of cross-contamination concerns. He discounted using his baton because he was afraid Mr. Willey could take it from him and he would be forced to resort to using his firearm. Yet, Constable Graham felt it was necessary to escalate the amount of force used to overcome the resistance. Constable Graham reported that he directed two punches at the lower abdomen of Mr. Willey. There was no change in the resistance offered by Mr. Willey.

After continuing the struggle for a few moments more, Constable Rutten was able to get Mr. Willey's arm behind his back and a second handcuff was applied to secure his arms together. At 5:23 p.m. Constable Rutten notified dispatch that they had Mr. Willey in custody. But even with Mr. Willey handcuffed, the officers reported that the struggle was not over. They continued to have difficulties controlling Mr. Willey. Mr. Willey was still kicking his legs and trying to roll over. Mr. Willey was bleeding from an injury to his mouth and officers feared him biting, spitting or kicking them.

Several independent witnesses reported seeing the struggle to take Mr. Willey into custody and came forward. Some were called to give evidence at the coroner's inquest. One witness who saw the arrest testified as follows:

I saw two or three officers struggling with Mr. Willey. And my first impression it was a very violent scene, and I was at first shocked at how much force was being used, but as I watched he was so wild, he was so resistant and out of control. There were three officers there and I – my thought was I don't think three is gonna be enough.

She made similar comments in her statements to police during the investigation. Other witnesses confirm Mr. Willey's continued struggle with the police as they tried to handcuff him.

After the handcuffs were placed on Mr. Willey, Constable Graham asked that a paddy wagon be called to the scene. Unfortunately, although that vehicle would have been preferable given its design, it was not available to provide immediate assistance to officers at the scene. Constable Graham then made the decision to apply the hog-tie.Footnote 6 He knew that the rope was in the glove box of his cruiser and he had been trained in the technique at the RCMP Training Academy. As he later reported, the hog-tie was the only thing he had available to satisfy the need to further restrain Mr. Willey. Constable Graham felt he had no other option available to him.

Constable Fowler retrieved the rope from Constable Graham's glove box. Once Mr. Willey's feet were secured, the officers were able to get off of him and hoped that he would now calm down. But, as Constable Fowler reported, Mr. Willey continued to squirm and "was trying to free himself".

Constable Glen Caston was operating a marked police Suburban vehicle, which had bars installed on the side windows in the passenger compartment. In response to radio transmissions calling for the paddy wagon, Constable Caston offered to assist. Constable Caston responded to the scene Code 3 (emergency/lights and sirens) and arrived at 5:26 p.m. He observed Mr. Willey lying on his stomach on the ground; there was some blood on the pavement. Constable Caston noted that there did not appear to be any blood flowing, but he did see blood on Mr. Willey's face around the area of his mouth.

Constables Caston and Graham lifted Mr. Willey into the rear compartment of the police vehicle through the passenger side. Constable Rutten reached in through the opposite door and assisted by pulling Mr. Willey along the seat into the vehicle. As Constable Caston recorded in his report, he was trained and worked with a Level 3 Industrial First Aid certificate for several years. He recognized the need to ensure that Mr. Willey was in the "recovery position," meaning that his ability to breathe was unobstructed. Constable Caston positioned Mr. Willey accordingly.

Constable Caston reported that at that point there was a discussion about where Mr. Willey ought to be taken—to the hospital or the cell block. Constable Caston observed that it was not normal practice to take a violent person to the hospital. Constable Graham made the decision that Mr. Willey would be taken to the cell block. As he later reported, he decided not to take him to the hospital because at the time the Prince George Regional Hospital had no place for someone in that state. He felt that given the violent behaviour and strength demonstrated by Mr. Willey, taking him to the hospital presented too much risk for the officers, hospital staff and the public.

Once Mr. Willey was safely loaded into the police vehicle, Constable Graham used his radio to advise the dispatcher that no other units were required. He also requested that an officer with a Taser® meet Constable Caston at the cell block. Constable Graham later explained that he made that request because, according to his training at the time, it was permissible to use a CEW on persons who were non-compliant. Given the level of force required to subdue Mr. Willey at the scene, Constable Graham believed that a CEW was "the least" means of force for someone in Mr. Willey's state.

d. Arrival and Treatment at the Detachment

At 5:27 p.m., Constable Caston left the scene transporting Mr. Willey to the detachment. The drive to the detachment took approximately two minutes. At 5:27 p.m., Constable Jana Scott and Constable Kevin O'Donnell arrived at the detachment to assist Constable Caston with Mr. Willey. They were waiting in the security bay when Constable Caston arrived. (Constables Rutten and Graham had both been exposed to the blood and bodily fluids of Mr. Willey and drove to the hospital to use their facilities to treat any wounds and to wash up. Constable Fowler returned to the detachment.)

The cell block video shows that Constable O'Donnell and Constable Caston both secured their firearms in the lock-up as required by RCMP policy.Footnote 7 Both were carrying CEWs. Constable Jana Scott retained her firearm. Constable O'Donnell, who had not been at the scene where the arrest occurred, had apparently determined that Mr. Willey would not be removed from the vehicle unless there was "lethal force over watch" present. Constable Scott remained in the security bay and drew her firearm to provide that "lethal force over watch."

Constable O'Donnell and Constable Caston both put on protective gloves. In the video, Constable O'Donnell can be seen holding a CEW in his left hand from the point where Mr. Willey is removed from the vehicle.

Removal from the Police Vehicle and Transport to Cell Block

At 17:30:42Footnote 8 Mr. Willey was removed from the police vehicle via the passenger side door. The best visual perspective of these actions would have been provided by a camera located in the security bay identified in the recording system as 4-03. However, at the moment when Mr. Willey was being removed from the police vehicle, the system stopped recording the video feed from that camera. The failure of the recording system has been the subject of expert review and is dealt with later in this report.

Constable Caston described the removal of Mr. Willey as follows:

At first attempt, writer reached in and tried to have him sit up, at this [time] WILEY started to struggle again, trying to kick his legs out at writer. WILEY was still restrained and unable to kick but did start to struggle around so that writer could not have him sit up. He was then pulled out of the vehicle by Cst. O'DONNELL and writer. Members were only able to reach his legs and used the tie for his feet to pull him from the car, his eventual fall to the ground outside of the car was as controlled as possible but as he came out of the vehicle, WILEY landed on the ground on his right side and writer believes that he bumped his head and shoulder on the door and door frame area of the vehicle. During this time WILEY was making a noise almost like he was growling at members. Once outside on the floor beside the truck, members grabbed onto him and pulled him to the elevator, taking him up to the cells area of the detachment.

Constable O'Donnell also described the act of removing Mr. Willey from the vehicle. In his "Will Say," Constable O'Donnell reported that:

He and Cst. CASTON removed WILLEY from Cst. CASTON's police vehicle;

WILLEY was handcuffed and hog-tied at this time;

While removing WILLEY from the police vehicle he observed WILLEY fell [sic] approximately three feet from the seat to the prisoner bay floor.

Constable O'Donnell provided further detail in his occurrence report as follows:

Cst O'Donnell stood to Cst Caston's left as Cst Caston first reached into the back of the police suburban on the passenger side of the vehicle. Cst O'Donnell observed Cst Caston back out of the passenger door area. Cst O'Donnell assisted Cst Caston in removing the prisoner from Cst Caston's suburban. Cst O'Donnell, standing to the left of Cst Caston looked into the passenger area and observed the prisoner was lying with his head towards the passenger side door on the driver's side. Cst O'Donnell, using right hand, reached in and grabbed onto the prisoners feet area. Cst O'Donnell noted that the prisoner was handcuffed as well as hog-tied. Cst O'Donnell, along with Cst Caston, pulled the prisoner out of the passenger area of the suburban in a controlled manner. When the prisoner was pulled out of the suburban Cst O'Donnell observed that the prisoner fell approx 3 feet from the seat to the prisoner bay floor. It appeared that the prisoner briefly glanced off but did not strike hard in any event his shoulder/right side of his head on the bottom of the door frame. The prisoner ended up on his right side on the cellblock bay floor.

Constable Jana Scott, who was providing "lethal force over watch" at the time, described the act of removing Mr. Willey as follows in her Will Say statement:

She observed WILLEY being removed from Cst. CASTON's police vehicle. He was removed slowly from the vehicle and did not strike his head.

Constable Scott provided additional information in her occurrence report. She wrote:

The back door of 13A1 was opened; the male was pulled out of the back feet first, his feet hit the ground, followed by his legs, hips, upper torso, and then the side of his face/cheek. The male came out of the back of the vehicle slowly, on the side of his body, and not hard, the male did not strike head down.

The perspective provided by the only camera working in the security bay at the time Mr. Willey was removed shows a view that is obstructed by the police vehicle. The view shows the passenger side door open at 17:30:25. There is then a view of the heads and upper bodies of Constable Caston and Constable O'Donnell as they remove Mr. Willey from the vehicle and move him towards the hallway which leads to the elevator to the cell block. Constable John Edinger was also present in the security bay around this time.

The floor of the security bay is concrete. There is an aluminum threshold at least one inch high at the doorway leading from the security bay to the hallway. The floor in the hallway is covered with a hard, rubberized material. The members do not stop as they travel from the vehicle to the doorway. In their occurrence reports, the members describe the transport of Mr. Willey from the security bay to the elevator as follows:

Constable Scott – Mr. Willey was "picked up by the shoulders and taken down the hallway to the elevator."

Constable Caston – "Writer recalls that Wiley was pulled to the elevator along the floor with members holding his upper torso off of the ground by his upper arms."

Constable O'Donnell – "Cst O'Donnell assisted in carrying the prisoner to the elevator. Once the elevator door opened up the prisoner was placed face down on the floor of the elevator with his feet closest to the elevator door."

Constable Edinger – "Writer assisted Cst O'DONNELL in moving subject to elevator. Elevator door opened."

However, the detachment video clearly shows that at 17:30:53 Mr. Willey was dragged face down while Constable O'Donnell and Constable Caston held him by his lower legs and not by his upper arms. From this point on, I rely heavily on the detachment video, as it provides a more reliable and objective record of Mr. Willey's treatment than the aforementioned reports.

At 17:31:05, Constable John Edinger can be seen taking hold of the hog-tie near Mr. Willey's ankles to assist in turning Mr. Willey so he can go into the elevator head first. The video shows that as they turn Mr. Willey, his head may have struck the door frame at the elevator door. The video in the elevator shows Constable O'Donnell with his right foot on Mr. Willey's back during the short ride up to the second floor. Constable O'Donnell can be seen holding his CEW in his left hand. The elevator ride lasted approximately 10 seconds.

At 17:31:32, the elevator arrived on the second floor and Mr. Willey was dragged out by Constable Caston and Constable O'Donnell, face down by his ankles. As Mr. Willey was removed from the elevator, he slides onto a carpet which is then dragged along under him. At 17:31:43, Mr. Willey can be seen on the video lying face down in the booking area on the carpet.

Call for Ambulance

On the ground level, Constable Scott holstered her firearm and waited for the elevator to return to the ground floor. When she arrived in the booking area, she was asked to call an ambulance. At 17:33:03, Constable Scott can be seen on the video using her radio. She contacted the Operational Communications Centre (OCC) and requested that they contact the ambulance service. She asked them to send Advanced Life Support, Code 3, so that Mr. Willey could be sedated, as he was not cooperating. Constables O'Donnell and Caston also noted the reasons for calling the ambulance as for the purpose of sedation as opposed to treating any physical injury.

CEW Deployment

Shortly after they arrived in the booking area, the video shows Constable Caston conducting a search of Mr. Willey. Constable O'Donnell placed his left foot on Mr. Willey's back. At 17:33:14, Constable O'Donnell placed his CEW on Mr. Willey's back. At about the same time, Constable Caston placed his CEW against Mr. Willey's upper right arm. It appears from the video that both members activated their CEWs at roughly the same time. According to their reports, the CEW had no effect on Mr. Willey.

Arrival of Ambulance

According to the time recorded by the BC Ambulance Service, the ambulance arrived at the detachment at 5:36 p.m. The ambulance attendants found Mr. Willey handcuffed on the floor, face down. He was spitting and moaning incomprehensible sounds. He was also reportedly lifting his head and feet up and rocking in a violent manner. At 17:43:32, Mr. Willey was placed on the ambulance gurney in preparation for transport to the hospital. At 17:46:16, Mr. Willey is last seen on the videotape as the ambulance gurney is wheeled out the doorway into a hallway in the detachment. Constables O'Donnell and Caston rode in the ambulance with Mr. Willey. Since the ambulance attendants had assessed Mr. Willey's vital signs as being stable, the ambulance was driving to the hospital Code 1 (i.e. without lights and siren). As the ambulance approached the Prince George Regional Hospital, Mr. Willey went into cardiac arrest. He died in hospital the following day.

Autopsy of Mr. Willey

Mr. Willey's autopsy was performed by Dr. James McNaughton at the Royal Inland Hospital in Kamloops on July 24, 2003. Corporal G. A. Doll of the Prince George Forensic Identification Section (FIS) was present at the autopsy. In his report, Dr. McNaughton described the various injuries he noted on the body and offered an opinion that death was due to a "probable cocaine overdose." Toxicology results later confirmed that opinion. Medical records reveal prior occasions where Mr. Willey was hospitalized and diagnosed as suffering the effects of drug abuse.

Although Mr. Willey sustained injuries during his arrest and detention, Dr. McNaughton determined that none of those injuries contributed to his death. During the coroner's inquest in October 2004, Dr. McNaughton testified at length and reported that in his view, the Taser® played no role in Mr. Willey's death. The coroner's jury found that Mr. Willey's death was due to a cocaine overdose.

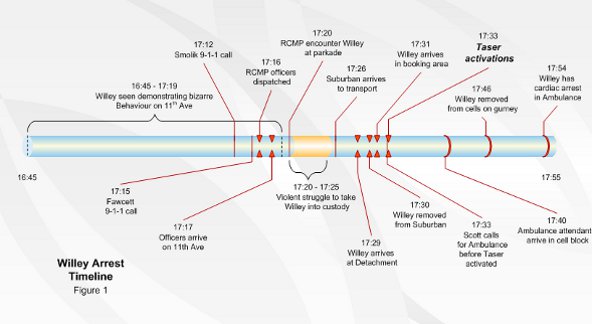

Arrest Timeline

Figure 1 illustrates the sequence and timing of events. It is based on a comprehensive review of witness statements, 911 and OCC transcripts, Unit Histories, officers' notes and occurrence reports.

Text Version

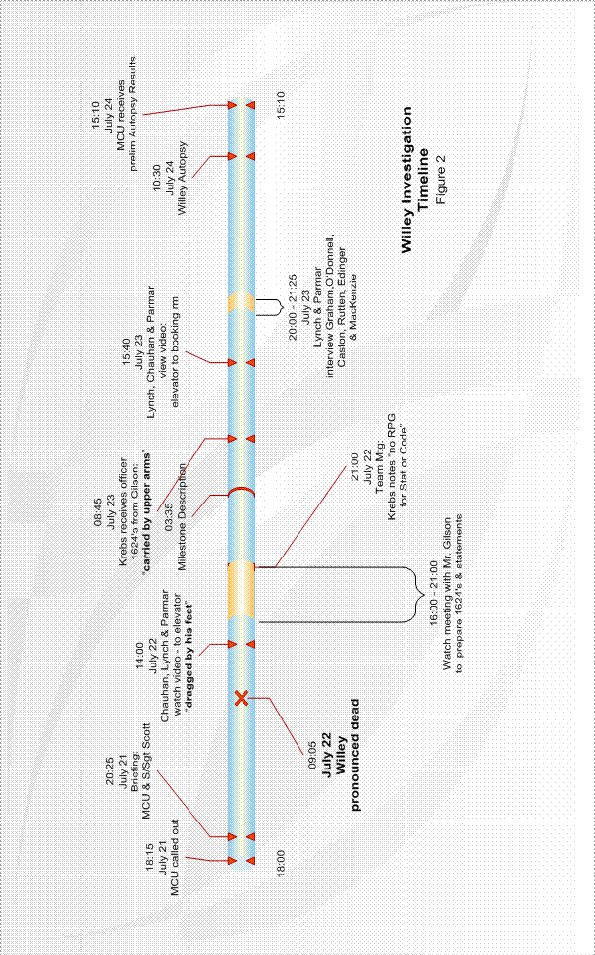

Appendix I: Investigation Timeline

July 21, 18:15 – MCU called out

July 21, 20:25 – Briefing: MCU and S/Sgt Scott

July 22, 09:05 – Willey pronounced dead

July 22, 14:00 – Chauhan, Lynch and Parmar watch video - to elevator “dragged by feet”

July 22, 16:00-21:00 – Watch meeting with Mr. Gilson to prepare 1624’s and statements

July 22, 21:00 – Team Meeting: Krebs notes “no RPG for Stat or Code”

July 23, 03:35 – Milestone Description

July 23, 08:45 – Krebs receives officer 1624’s from Gilson: “carried by upper arm”

July 23, 15:40 – Lynch, Chauhan and Parmar view video: elevator to booking room

July 23, 20:00-21:25 – Lynch and Parmar interview Graham, O’Donnell, Caston, Rutten, Edinger and MacKenzie

July 24, 10:30 – Willey Autopsy

July 24, 15:10 – MCU receives prelim autopsy results

Analysis – Compliance with Policies, Procedures, Guidelines and Statutory Requirements

When responding to calls from the public, RCMP members are subject to the duty provisions of the RCMP Act, and in particular paragraph 18(a), which states:

It is the duty of members who are peace officers, subject to the orders of the Commissioner, (a) to perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada and the laws in force in any province in which they may be employed, and the apprehension of criminals and offenders and others who may be lawfully taken into custody [...].

In executing their duties, police officers are guided by policy and are authorized by the Criminal Code to use as much force as necessary.Footnote 9 However, the officer must be acting on reasonable grounds. Police officers are also justified in using as much force as is reasonably necessary to prevent the commission of an offence for which a person may be arrested without warrant, or that would be likely to cause immediate and serious injury to the person or property of anyone; or to prevent anything being done that he or she believes, on reasonable grounds, would be the commission of such an offence.Footnote 10

In determining whether the amount of force used by the officer was necessary, one must look at the circumstances as they existed at the time the force was used. The courts have been clear that the officer cannot be expected to measure the force used with exactitude.Footnote 11

Police Intervention and Use of Force

At the time that constables Fowler, Graham and Rutten came into contact with Mr. Willey, they were investigating a complaint of bizarre and threatening behaviour. When they first encountered Mr. Willey he was acting aggressively towards a security guard and then towards Constable Fowler. Attempts to speak to him were unfruitful and the officers' commands were ignored by Mr. Willey.

It is clear from the Commission's review of all of the information before it that constables Graham and Fowler were acting in the course of their duty when they started to interact with Mr. Willey. They were investigating a disturbance and found Mr. Willey behaving aggressively. Rather than following the instructions of the members, Mr. Willey continued to advance towards Constable Fowler.

Based on all of the information available to constables Graham and Fowler, they had reasonable grounds to believe that Mr. Willey was causing a disturbance contrary to section 175 of the Criminal Code. He was intoxicated and interfering with other persons (including disturbing the peace and quiet of residents in the neighbourhood), and the members had a duty to take action. The members reasonably believed that Mr. Willey posed a threat to himself and to others and that it was necessary to arrest him. Such an arrest was justified under section 495 of the Criminal Code, as the members had reasonable grounds to believe Mr. Willey would continue that behaviour. As the situation evolved, Mr. Willey became increasingly aggressive and violent. The situation escalated so quickly that none of the members had the opportunity to tell Mr. Willey that he was under arrest.

Finding: The members entered into their interactions with Mr. Willey lawfully and were duty-bound to do so.

The RCMP has adopted an Incident Management/Intervention Model (IM/IM)Footnote 12 that allows for training and supervision of members to ensure compliance with the principles set out in the Criminal Code with respect to the use of force. Under the IM/IM, use of force is scalable starting with a verbal request for compliance and increasing use of force to compel compliance up to the use of deadly force. There were seven principles underlying the model that was in place at the time of the incident:

- 1) The primary objective of any intervention is public safety.

- 2) Police officer safety is essential to public safety.

- 3) The intervention model must always be applied in the context of a careful assessment of risk.

- 4) Risk assessment must take into account: the likelihood and extent of life loss, injury and damage to property.

- 5) Risk assessment is a continuous process and risk management must evolve as situations change.

- 6) The best strategy is to utilize the least amount of intervention to manage the risk.

- 7) The best intervention causes the least amount of harm or damage.

It is incumbent upon the member to perform a risk assessment, first determining which of the five behaviour classifications (cooperative, non-cooperative, resistant, combative and potential to cause grievous bodily harm or deathFootnote 13) the subject's actions fall into. Consideration must also be given to the situational factors specific to each incident. These include weather conditions, subject size in relation to the member, presence of weapons, number of subjects and of police, the perceived abilities of the subject (which may include past knowledge of the subject), as well as a host of other incident-specific considerations.

Intervention Options

The IM/IM sets out various response or intervention options specific to the member's determination of subject behaviour in conjunction with the assessment of the situational factors. Intervention options include officer presence, verbal intervention, empty hand control (soft and hard), intermediate devices, impact weapons, lethal force and tactical repositioning. As diagrammed, in recognition of the dynamic nature of these incidents, the IM/IM is not a linear structure such that one response necessarily leads to another. Rather, the IM/IM is intended to train RCMP members with respect to the need to constantly assess the risk and potential for harm and to respond at an appropriate level.

Verbal interventions and tactical repositioning occur regardless of the level of risk to assist the member in maintaining control of the situation, de-escalating any confrontation and ensuring maximal safety for all concerned. Throughout the management of an incident, a member should be alert to threat cues such as body tension, tone of voice, body position and facial expression to ready them to use an appropriate response option. These threat cues may indicate the potential for a suspect to display more or less resistant behaviours described under the categories of resistance that would justify the use of different response options.

Application of Force at the Scene of the Arrest

The statements of constables Graham, Fowler and Rutten indicate that they were aware of the following when they first encountered Mr. Willey: Mr. Willey was acting erratically and possibly possessed a knife. He was in an open and public place, and was confronting a civilian—the Parkwood Mall security guard. Mr. Willey was well known to the RCMP in Prince George. At the time of this incident, he was 33 years old, measured approximately 5'10" and weighed 155 pounds.

Mr. Willey appeared to have blood and foam on his mouth. His eyes were glazed over, red, and unnaturally wide. He was growling like a dog and had his hands clenched into fists. He appeared to be under the influence of drugs. When Mr. Willey was asked to calm down and to get on the ground, he was unresponsive. When the members took him to the ground, he resisted and displayed shocking strength; he was unresponsive to pain control. He was a known intravenous drug user, and the members had concerns for their safety if they came into contact with his bodily fluids.

a) Use of physical force to contain Mr. Willey

Prior to taking Mr. Willey to the ground, Constable Graham approached him with his firearm drawn due to the concern that Mr. Willey had a knife on him. (Although the cell phone was found in the backyard, the members could not ignore the possibility that Mr. Willey may still have a knife.) Constable Graham holstered his weapon when he could see both of Mr. Willey's hands and that they did not contain a knife. As the presence of a weapon supports a reasonable fear of grievous bodily harm or death, I find that Constable Graham's decision to draw his firearm, particularly given the potential danger to a civilian in the area, was reasonable in the circumstances.

After determining that Mr. Willey's hands did not hold weapons, Constable Graham believed that he would be able to take Mr. Willey to the ground using an arm bar technique, which was ultimately successful. The use of an arm bar hold coupled with taking a suspect to the ground are known as soft empty-handed control techniques. They are consistent with the IM/IM and appropriate for use when, as here, verbal interventions have failed.

When Mr. Willey was on the ground, the members managed to attach a handcuff to one arm but had difficulty gaining control of Mr. Willey's other arm. Constable Rutten applied two kicks to Mr. Willey's upper chest area. Constable Rutten felt that he was justified in using kicks to overcome the resistance demonstrated by Mr. Willey. Both of his hands were being used to restrain the arm that was already handcuffed. He was focused on bringing his hand behind his back to secure the handcuffs. Constable Graham stated that he struck Mr. Willey twice in the area of his left side with the intent of having him react in order to free his arm, which Mr. Willey had locked by his side. Strikes and kicks are known as hard empty-handed control techniques. Given Mr. Willey's active resistance to the arrest attempt and his combative behaviour at the time these techniques were applied (he was continually kicking and writhing), I find that such use of force was reasonable in the circumstances.

I note that there were two witness statements that suggested that the RCMP members used additional and unreasonable force against Mr. Willey. Both witnesses knew Mr. Willey. One indicated that after the police vehicle arrived, "that's when Clay really started getting whacked"—he "got the boots instantly." A second witness indicated that there were eight officers attacking one male, four kicking him and standing on his head and four punching him. I find that these statements lack any credibility, as they are wholly inconsistent with every other statement from both civilian and member witnesses.

Finding: The force used by constables Graham and Rutten to arrest and apply handcuffs to Mr. Willey was reasonable in the circumstances.

b) Use of OC sprayFootnote 14

Constable Rutten considered the intervention options open to him in the situation and decided to use OC spray prior to Mr. Willey being handcuffed. He sprayed OC spray directly into the centre of Mr. Willey's face from a distance of about twelve inches. At that point, pain compliance techniques were not working to bring Mr. Willey under control. However, the OC spray also did not produce the desired result, as there was no change in the level of resistance offered by Mr. Willey.

When Constable Graham was interviewed by the Commission's investigator, he stated that he had considered and discounted using OC spray for several reasons. He was concerned that using OC spray in those circumstances posed an unacceptable risk of cross-contamination. He also doubted that OC spray would be effective on a subject in the condition that Mr. Willey was in.

While Constable Rutten's use of OC spray may have been ill-advised given the risk of cross-contamination, I find that he reasonably believed that it could assist in bringing Mr. Willey under control and, consequently, that its use was proportional and reasonable in the circumstances.

Finding: Constable Rutten's use of OC spray during the struggle with Mr. Willey at the parkade was ill-advised, but not unreasonable in the circumstances.

c) Use of hog-tie

By all reliable reports, even when the handcuffs were applied to restrain Mr. Willey's wrists, the struggle was not over. Constable Graham stated that given Mr. Willey's state, he needed some method of preventing Mr. Willey from kicking or running away.

The hog-tie had been discontinued by the RCMP as of May 2002. A bulletin had been issued by the National Contract Policing Branch after the Operational Policy Group—Community, Contract and Aboriginal Policing Services—concluded that the RIPP Hobble prisoner restraint device was a viable alternative to the hog-tie and was approved for operational use. However, in July 2003 front-line police officers in Prince George had not yet been trained or equipped to use the RIPP Hobble, and the rope used to apply the hog-tie was still carried in RCMP vehicles. At the coroner's inquest in 2004, Constable Graham stated that he was unfamiliar with the RIPP Hobble and had not received any training on it.

Constable Graham reasonably concluded that he needed to secure Mr. Willey's legs. He considered his options and decided to apply a hog-tie. That decision was contrary to existing RCMP policy.Footnote 15 However, it is important to note that using restraints that are not approved pursuant to RCMP policy does not make their use unreasonable per se. I find that Constable Graham's decision to apply a hog-tie was reasonable, as he had no other available options to secure Mr. Willey's legs and reasonably feared that Mr. Willey would get up and continue fighting. Constable Graham's options were limited because the RCMP had failed to implement its policy decision on the RIPP Hobble in a timely fashion.

Given that body position is often listed as an antecedent or contributing cause of death in in-custody death cases, which led to the change in policy, the RCMP ought to ensure that members understand the potential impact of using prohibited restraint mechanisms. As such, the Commission recently recommended in its report respecting deaths in RCMP custody proximal to the use of the CEW (July 2010) that "the RCMP develop and communicate to members clear protocols on the use of restraints and the prohibition of the hog-tie, modified hog-tie and choke-holds." The Commission reiterates that recommendation.

Findings

- It was reasonable for Constable Graham to apply the hog-tie in the circumstances despite its use having been discontinued by the RCMP.

- The RCMP failed to implement its change in policy with respect to the discontinued use of the hog-tie and approved use of the RIPP Hobble in a timely manner.

Recommendation: The Commission reiterates its recommendation in its report respecting deaths in RCMP custody proximal to the use of the CEW (July 2010) that "the RCMP develop and communicate to members clear protocols on the use of restraints and the prohibition of the hog-tie, modified hog-tie and choke-holds."

Summary

In my view, it was clear that Mr. Willey was not acting rationally at the time of his arrest and was not capable of understanding the consequences of his actions. Due to his unpredictable and violent behaviour, it was necessary to restrain him by means of physical force. Considering all the available information and taking into account the behaviour displayed by Mr. Willey, I find that constables Graham, Fowler and Rutten had a reasonable fear of physical harm to themselves or others that led them to exercise their use of force options in a manner consistent with the policies of the RCMP and the legal statutes.

Finding: Constables Graham, Fowler and Rutten utilized an appropriate level of force when effecting the arrest of Clay Willey on July 21, 2003.

Application of Force Following Initial Arrest

Mr. Willey was transported from the scene of the arrest to the Prince George RCMP Detachment cells. Upon arrival, constables Kevin O'Donnell, Glenn Caston, Jana Scott, and John Edinger were present. They were aware that Mr. Willey had been combative and difficult to control during his initial arrest. Upon arrival at the detachment, Mr. Willey continued to strain against his restraints. Mr. Willey was generally non-communicative (other than grunting and making other incoherent noises), and had blood on his head area (although there was no apparent ongoing flow of blood) and a white foam on his mouth. A number of the members confirmed in their statements that they believed Mr. Willey to be on drugs.

a) Removal from police vehicle and transport to cell block

Mr. Willey was removed from the police vehicle shortly after arriving at the Prince George RCMP Detachment. Constable Caston noted in his statement that he and Constable O'Donnell "locked up [their] guns in the bay lockers as per RCMP policy" and proceeded to remove Mr. Willey from the vehicle. Constable Scott indicated that Constable O'Donnell would not take Mr. Willey out of the vehicle without "lethal force over watch," a tactical technique normally used in the field when dealing with an individual who is not restrained. As such, she stayed in the bay area with her firearm out while Mr. Willey was removed from the police vehicle. We have no further explanation as to why the firearms policy was not followed. Constable Edinger stated in an interview with RCMP investigators that he did not secure his firearm, but rather kept it on him, as he sensed urgency when he arrived to assist.

RCMP policy provides that firearms are not to be carried when entering the cell block area or secure bay.Footnote 16 However, if a member believes it is warranted to do so, the member must "conduct a risk assessment taking into consideration [his or her] safety, the safety of prisoners and that of other individuals in the immediate area."Footnote 17 Lethal force over watch is a tactical technique normally used in the field when dealing with an individual who is not handcuffed and hog-tied. In my view, there was neither an urgency to the removal of Mr. Willey from the police vehicle that prevented Constable Edinger from securing his firearm nor any explanation provided in the statements of constables Scott and O'Donnell that justified a need for lethal force over watch that would otherwise be prohibited by RCMP policy.

According to the law and RCMP policy, a firearm is a permitted use of force only where a member perceives a threat of death or grievous bodily harm. It is a weapon of last resort. The Criminal Code only provides protection to police officers who use force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm if the officer had reasonable grounds to believe that it was necessary to protect against sameFootnote 18. In my view, Constable Scott having her firearm drawn while Mr. Willey was being removed from the vehicle (handcuffed and hog-tied) was an overreaction and unjustified in the circumstances.

Finding: Constables Scott and Edinger failed to secure their firearms upon arrival at the detachment as required by RCMP policy and were not justified in deviating from that policy.

Finding: It was not an appropriate use of force for Constable Scott to have her firearm drawn at the time of Mr. Willey's removal from the police vehicle.

As noted above, Mr. Willey was pulled from the police vehicle by his feet, with no support given to his upper body. I note that neither Constable Caston nor Constable O'Donnell had been at the scene and fought to subdue Mr. Willey. They were trained professionals and had a number of options available to them in removing Mr. Willey. Time was on their side. I note that as he was holding his CEW in one hand, Constable O'Donnell had only his right hand available to assist Constable Caston in removing Mr. Willey from the police vehicle. If they were concerned about the possibility that he would kick and injure them, they could have removed him head first via the driver's side door. They had donned protective clothing and could have used other measures if they were concerned that he might spit blood at them.

Another alternative was to cushion his fall as Mr. Willey slid off the end of the back seat. Or the members could have asked for help, as there were others available in the office nearby who could have assisted. Neither Constable Scott nor Constable Edinger assisted with the removal. Rather, Constables Caston and O'Donnell chose to pull Mr. Willey out feet first, without anyone or anything to break his fall when he came off the end of the back seat. Consequently, Mr. Willey was pulled out and fell, first striking the door frame and then landing on the concrete floor. He did not have his hands available to help break his fall and no one else assisted him. The reason they chose to remove him from the vehicle in that fashion was not canvassed during the investigation and, in my view, their actions were unreasonable.

RCMP Inspector Tom Gray, who conducted the Independent Officer Review (discussed later in this report), recognized that the removal was a potential problem. During an interview with the Commission's investigator, Inspector Gray identified the method used by the members to remove Mr. Willey from the vehicle as "an obvious concern". He indicated that he had thought about the situation but concluded that the members did not intend to hurt Mr. Willey. Concern was also expressed by the regional Crown counsel who reviewed the file, but the decision was made not to lay criminal charges against the members. The RCMP's own use of force expert, Corporal Gregg Gillis, testified at the coroner's inquest that, without an explanation for the method of removal, there was certainly a better way to remove Mr. Willey from the vehicle, which would be to pull him out by hooking their arms under his shoulders to allow for better control of his upper body and head.

Given the treatment Mr. Willey was subjected to as demonstrated by the cell block video, I have no doubt that no additional care was taken when dragging Mr. Willey face down across the elevated aluminum threshold in the doorway that connected the security bay to the hallway to the elevator. As he was dragged through the hallway, the video shows a trail of liquid from his face or mouth being transferred to the floor. Even the members' supervisor, Staff Sergeant John Scott, told the Commission's investigator that it is not generally appropriate to drag a prisoner face down; he said if you have to drag them, it would be more appropriate to turn them around so that their shoulders are on the ground.

The placement of Mr. Willey into the elevator demonstrated no improvement in his treatment. He was again dragged by the feet, face down, and it appears on the video that his head may have hit off the elevator door. No attempts were made to facilitate a more controlled transfer, despite there being four members present.

While I acknowledge that Mr. Willey was a difficult subject due to his constant movement and physical resistance, I find that the members treated him with a level of callousness that was unwarranted. The members owed a duty to care to Mr. Willey while he was in their custody. RCMP policy provides that "a person in RCMP custody will be treated with decency and provided with all the rights accorded to him/her by law."Footnote 19 I find that the members failed to treat Mr. Willey with the level of decency to be expected when he was removed from the police vehicle and transported to the elevator.

Finding: Constables Caston and O'Donnell failed to treat Mr. Willey with the level of decency to be expected from police officers when they removed him from the police vehicle and transported him to the elevator.

b) CEW deployment

Under the Criminal Code, the CEW is a prohibited firearm and can only be used by law enforcement officers. The Commission has been steadfast in its position that when used appropriately, the CEW can be an effective tool for the RCMP. The Commission has also maintained that the CEW causes intense pain, it may exacerbate underlying medical conditions, and it has been used in situations where its use is neither justifiable nor in accordance with RCMP policy.

The Commission made a number of recommendations to the RCMP in its report RCMP Use of the Conducted Energy Weapon (CEW) in June 2008, its Report Following a Public Interest Investigation into a Chair-Initiated Complaint Respecting the Death in RCMP Custody of Mr. Robert Dziekanski in December 2009, as well as a number of other reports issued by the Commission since the RCMP began using the CEW. Many of those recommendations have been implemented by the RCMP; some have not.

RCMP policy has consistently recognized the need to assess other means of intervening to calm or subdue a suspect, and has required from the outset (absent an operational situation which would preclude such a step) that members identify themselves as peace officers and issue a warning prior to deploying the CEW. Current RCMP policy recognizes that multiple deployments of the CEW may be hazardous to a subject.

Both Constable Caston and Constable O'Donnell had been certified in the use of the CEW the month prior to their encounter with Mr. Willey, and so were authorized by RCMP policy to use the weapon. They appear to have been of the same mind with respect to the use of the CEW in these circumstances, as they are seen on the cell block video simultaneously using their CEWs in push stun mode.Footnote 20 While there has been some dispute as to how many times the CEW was used on Mr. Willey, the video and medical evidence, as well as the statements of the members, indicate that each member activated their CEW only one time.Footnote 21

Constable Caston described his reasons for deploying the CEW as follows:

During the time that WILEY was in cells, the tazer was used in stun mode to try and get WILEY to settle down. In "stun" mode no projectiles (darts) are used. The idea when using a tazer is to provide a pain stimulus that the person reflects on when they continue the dangerous behavior. The idea is to have the individual focus on the localized pain to try and bring some reality to their thought process. The tazer was used on his right arm once by writer and once on his back by Cst. O'DONNELL. Hopes are that the person responds to the first incident and calms. This was not the case with WILEY, he remained combative.

Constable O'Donnell described his reasons for deploying the CEW as follows:

For a number of minutes, there were only Cst. O'Donnell and Cst. Caston attempting to control the prisoner. Cst. Scott and Cst. Edinger were also present. Cst. O'Donnell administered the taser one time using the touch stun in attempts to control the prisoner during one of his fits of rage when he was squirming around. In using the touch stun mode of the taser, Cst. O'Donnell was hoping to gain pain compliance and stop the prisoner from squirming around using the minimal amount of force necessary. [...] Cst. O'Donnell administered the taser because he didn't want to have to wrestle or go near the prisoner's head due to his bleeding.

At the time of the incident, RCMP policy provided that the "CEW may only be used to subdue individual suspects who resist arrest, are combative or suicidal."Footnote 22 The CEW was characterized "as a less lethal means for controlling suspects and averting injury to members, suspects and the public."Footnote 23 The members' justification for its use appears to have been on the basis that Mr. Willey was continuing to resist arrest and there was a risk that if he broke free of his restraints, he would be combative again.

According to the IM/IM, the key consideration in determining whether or not the members' CEW usage was appropriate in the circumstances is the assessment of the subject's behaviour. Whenever a police officer is engaged in an interaction with a member of the public it is incumbent upon that police officer to perform a risk assessment to ensure that his or her response is both reasonable and proportionate to the subject's behaviour. Despite the use of the term "combative" by Constable Caston in his report when referring to Mr. Willey's behaviour, it is clear to the Commission that Mr. Willey's behaviour at the time the CEW was used fell within the resistant category. There was no evidence to indicate that Mr. Willey was striking out at members; rather, he was straining against his restraints, which would constitute active resistance.

RCMP policy at the time specified that the CEW may be used against "suspects who resist arrest." In his testimony at the coroner's inquest, Corporal Gillis explained that while he considered resisting arrest and resistant behaviour to be two different concepts, he believed the use of the term "resisting arrest" in the CEW policy to cover both. I note that Corporal Gillis is very involved in the training of members with respect to the CEW and other uses of force. In my view, this illustrates the lack of clarity in the RCMP's former CEW policy, which was to guide the members at the time of this incident.

The RCMP's current CEW policy provides that a member must only use a CEW in accordance with "the principles of the Incident Management/Intervention Model (IM/IM) and when a subject is causing bodily harm, or the member believes on reasonable grounds, that the subject will imminently cause bodily harm as determined by the member's assessment of the totality of the circumstances."Footnote 24 It is clear to the Commission that the use of the CEW in Mr. Willey's circumstances would not meet the requirements of today's policy, as Mr. Willey was not, at the time of its use, causing bodily harm, nor did the members have reasonable grounds to believe that he would imminently cause bodily harm. However, I cannot measure the members' conduct in 2003 against today's policy.The change in policy reflects the RCMP's recognition that the CEW can cause more pain and potential injury than originally believed and taught to members. As Corporal Gillis stated in his evidence at the coroner's inquest, in 2003 members were taught to use the CEW for pain compliance; however, such actions as kicks and strikes were not recommended due to the likelihood of those actions causing a substantial injury to the subject. It is clear from his testimony, as well as statements from Staff Sergeant John Scott, that the seriousness of using the CEW was not communicated during training and members were taught to use the weapon when a subject was "non-compliant." That training simply does not adequately reflect what is and was required by law and is now reflected in RCMP policy.

While resistant behaviour may sometimes be classified as "non-compliant," it does not always equate to resisting arrest. The members wanted Mr. Willey to stop straining against his restraints; however, the fact remains that he was restrained. In my view, there is a significant difference between using a CEW to gain compliance from a subject in order to apply restraints when they are resisting the physical act of arrest and could potentially escape, and using a CEW to "calm down" a subject once they are already restrained.

I recognize that human responses may not always align exactly with policy, especially when those responses come about in the heat of an incident and reactive decisions are made intuitively without time to fully reflect on potential outcomes. It is for this reason that the training component is crucial to the outcome of an incident. If police officers are not trained to react in a manner that will bring about the most successful and least injurious outcome, the decisions taken in response to demonstrated behaviour will not be in keeping with the principles of the IM/IM and community expectations of the police. The result of such training might well have been that Constables Caston and O'Donnell were more inclined to deploy the CEW because of the position of the RCMP that the CEW is an effective, relatively safe and less harmful means to achieve an end.

That being said, I find it even more unacceptable that the members would use their CEWs simultaneously. That use was neither in accordance with RCMP policy nor a reasonable use of force in the circumstances. As noted in their reports, Constables O'Donnell and Caston's primary purpose in using their CEWs on Mr. Willey was for pain compliance, i.e. to inflict pain in an effort to reorient him and have him comply with instructions not to fight the physical restraints and to calm down. I understand that Constable O'Donnell had some concern that Mr. Willey could break his restraints, and had originally requested a restraint board, which was not available at the Prince George RCMP Detachment. However, while breaking his restraints was a possible outcome, it was not a probable outcome.

In addition, I find it difficult to accept that the breaking of restraints was an overriding concern since just prior to their simultaneous use of the CEW, neither officer used more than one hand (and at times used the same hand that held their CEW) and one leg from a standing position to counter Mr. Willey's pull on the restraints. Nor did they ask any of the nearby members to assist with restraining Mr. Willey while they waited for the arrival of the ambulance. I note that throughout the encounter, both prior to the use of the CEW and after, a number of members were in and out of the area observing what was happening. I also note that Constable Jana Scott is seen on the cell block video to be in the immediate area at the time the members chose to use their CEWs. The RCMP's CEW policy required the members to "consider other possible intervention options to calm or subdue"Footnote 25 Mr. Willey. In my view, they failed to do so.

Instead, Constables O'Donnell and Caston decided at the same time to use their CEWs on Mr. Willey without any apparent communication about their intention to do so and despite the fact that there were no urgent circumstances that necessitated the immediate application of the CEW. Constables O'Donnell and Caston failed to make an adequate risk assessment prior to taking such action.

Finding: The simultaneous use of the CEW by constables Caston and O'Donnell was unreasonable, unnecessary and excessive in the circumstances.

I note that RCMP policy dictates a reporting process for each usage of a CEW. A Conducted Energy Weapon Usage Report was not filed until sometime after the coroner's inquest. The form, which was completed by Staff Sergeant Scott, contains a reference to the findings of the inquest. It was only submitted in relation to Model M-26 Taser serial #010093, which was used by Constable O'Donnell. There is no record of a similar Usage Report filed in relation to the Model M-26 Taser Serial #011406 which was used by Constable Caston, although he is mentioned in the Report.

Finding: Constables Caston and O'Donnell failed to adequately document their use of the CEW and in a timely manner.

Obtaining Medical Treatment

The RCMP owes a duty of care to those in its custody, and its policies provide direction to members with respect to obtaining medical treatment for prisoners. At the time of Mr. Willey's arrest, the relevant policy stated, in part:

If medical sedation is warranted in restraining a person, contact a medical practitioner and ensure supervision.

It is the responsibility of the first member on the scene to complete an assessment of responsiveness. [...] If there is any indication that a person is ill, suspected of having alcohol poisoning, a drug overdose, or ingested a combination of alcohol and drugs, concealed drugs internally, or sustained an injury, seek immediate medical attention.Footnote 26

The ambulance was called by Constable Jana Scott on the direction of constables O'Donnell and Caston after they had arrived in the cell block. As noted above, the members all indicated that their intention in having paramedics attend the scene was to sedate Mr. Willey so that he would be adequately restrained and under control; it was not out of concern for any physical injuries that he incurred. The ambulance attendants were not in a position to sedate Mr. Willey, and so he was transported to the hospital. It was in the ambulance that he went into cardiac arrest.