Interim Report on the Chair-Initiated Public Complaint regarding the Shooting Death of Valeri George in Buick Creek, B.C.

Related Links

- Chair-Initiated Complaint

October 6, 2009 - Commissioner's Response

November 2, 2016 - Final Report

December 16, 2016

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act

Subsections 45.59(1)

Complainant

Chair of the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

File No.: PC-2009-2863

Table of Contents

Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

- Background

- Initial involvement of the RCMP

- Mr. George’s state of mind

- The George family property

- North District Emergency Response Team activation and deployment

Analysis of the RCMP’s Involvement with Mr. George from September 26 to 30, 2009

- Conduct of RCMP members prior to the activation of the NDERT

- a) Initial response and investigation

- b) Grounds to arrest Mr. George

- c) Application for a warrant

- d) Communications

- Activation of the NDER

- NDERT personnel

- NDERT briefing

- NDERT deployment

- Operational plan

- Observation of Mr. George

- Actions of the NDERT Crisis Negotiation Team

- Initial confrontation between the NDERT and Mr. George

- Tactical repositioning following initial confrontation between the NDERT and Mr. George

- Positioning of Corporal Arnold

- Communication of Corporal Arnold’s positioning

- Final confrontation and use of lethal force

- Non-lethal force and other tactical options

- Medical treatment following the shooting

- RCMP involvement following the shooting

- Member debriefing

Adequacy of Policy, Procedures and Guidelines

- Appendix A – Chair-Initiated Complaint: Shooting death of Mr. Valeri George at Buick Creek, in the Fort St. John area of British Columbia on September 30, 2009

- Appendix B – RCMP Response to the Chair-Initiated Complaint

- Appendix C – Summary of Findings and Recommendations

- Appendix D – List of Primary RCMP Members Involved in the Incident

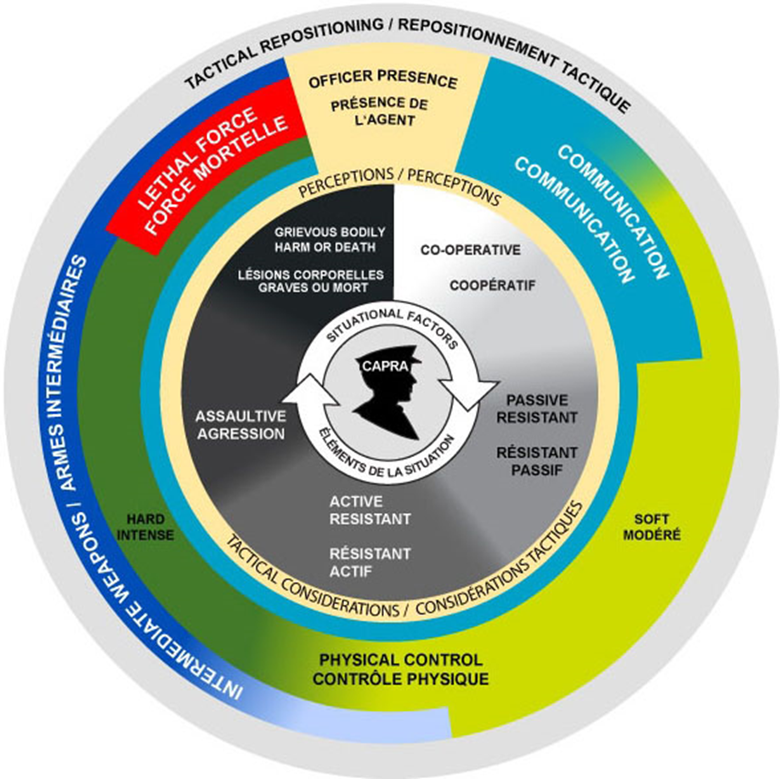

- Appendix E – RCMP Incident Management / Intervention Model

- Appendix F – Categories of Resistance of Individuals

Introduction

[1] On September 26, 2009, the Fort St. John RCMP in British Columbia was contacted by a member of the public with respect to an incident involving Valeri George and his family. It was reported that Mr. George stopped a vehicle containing his spouse and children, who were on their way to attend a wedding in another town, and shot out two of the tires with a rifle. The driver of the vehicle was able to proceed to a nearby residence, but Mr. George followed them and shot out the remaining two tires. Mr. George eventually returned to his residence following several failed attempts to speak with his family and to get them to return home. His family travelled on to the wedding and remained out of town until the matter could be resolved, on the advice of the RCMP. Attempts were made by members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment to speak with Mr. George, but he was not cooperative and insisted that his family be returned to him.

[2] The RCMP North District Emergency Response Team (NDERT) was ultimately activated, and on September 30, 2009, they were deployed to the area of Mr. George's residence to effect a warrant for his arrest. After numerous attempts by the RCMP to make contact with Mr. George to negotiate his surrender, Mr. George drove down his driveway, while carrying a firearm and at a high rate of speed. The NDERT had blocked Mr. George's exit from his property and it appeared that Mr. George was about to ram the barricade, placing at least one NDERT member at risk of serious harm or death. NDERT members fired on the vehicle and Mr. George, who died at the scene.

Chair-Initiated Complaint

[3] On October 6, 2009, the then Chair of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (now the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,Footnote 1 hereafter referred to as the "Commission") initiated a complaint (Appendix A) into the conduct of all RCMP members or other persons appointed or employed under the authority of the RCMP Act involved in this incident, as well as matters of general practice applicable to situations of this nature and, more specifically, those in which RCMP Emergency Response Teams are deployed. Specifically:

- whether the RCMP members or other persons appointed or employed under the authority of the RCMP Act involved in the events of September 26 to September 30, 2009, from the moment of initial contact through to the subsequent death of Mr. George complied with all appropriate training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements relating to the use of force; and

- whether the RCMP's national-, divisional- and detachment-level policies, procedures and guidelines applicable to such an incident and to situations in which RCMP Emergency Response Teams are deployed are adequate.

[4] As provided by the RCMP Act, the complaint was investigated by the RCMP, who provided the Commission with a Final Report dated June 11, 2012, attached as Appendix B. In summary, the RCMP found that the NDERT members acted appropriately and that the use of lethal force was necessary and reasonable, and that the policies, procedures and guidelines applicable to this incident were adequate.

[5] Pursuant to paragraph 45.71(3)(a) of the RCMP Act, the Commission is required to prepare a written report setting out its findings and recommendations with respect to its review of the complaint. This report constitutes the Commission's investigation into the issues raised in the complaint, and the associated findings and recommendations. A summary of the Commission's findings and recommendations can be found in Appendix C.

Commission's Review of the Facts Surrounding the Events

[6] It is important to note that the Commission is an agency of the federal government, distinct and independent from the RCMP. When reviewing a Chair‑initiated complaint, the Commission does not act as an advocate either for the complainant or for RCMP members. The Chair's role is to reach conclusions after an objective examination of the evidence and, where judged appropriate, to make recommendations that focus on steps that the RCMP can take to improve or correct conduct by RCMP members.

[7] It should also be noted that the findings and recommendations made by the Commission are not criminal in nature, nor are they intended to convey any aspect of criminal culpability. A public complaint involving the use of force is part of the quasi-judicial process, which weighs evidence on a balance of probabilities. Although some terms used in this report may concurrently be used in the criminal context, such language is not intended to include any of the requirements of the criminal law with respect to guilt, innocence or the standard of proof.

[8] The circumstances related to the death of Mr. George were also reviewed as part of an Independent Officer Review (IOR), which was conducted by RCMP Inspector Jeffrey Hunter. He issued a Final Report dated September 2, 2011. An IOR is an internal administrative review. The primary purpose of the IOR is a fact-finding enquiry to ensure, among other things, that a proper investigation was conducted; that officer training, skills, procedures, tactics and policy are appropriate and were followed; that member conduct was in accordance with the RCMP Act, and that any issues which brought about or contributed to the incident are identified and responded to.Footnote 2 In its report to the Commission, the RCMP stated that it relied in large part upon the findings of the IOR. The findings and recommendations of the IOR will be referenced throughout this report, where applicable to the issues being examined by the Commission.

[9] My findings, as detailed below, are based on a thorough examination of the following documents: the investigative report prepared by the RCMP's "E" Division Major Crime Section and supporting documentation, including statements, notes, reports and photographic and video evidence; relevant documentary materials as disclosed by the "E" Division; the IOR report; the RCMP's Final Report to the Commission; and other relevant documentation.

[10] The following account of events flows from witness statements provided during the police investigation. The Commission puts these facts forward, as they are either undisputed or because, on the preponderance of evidence, the Commission accepts them as a reliable version of what transpired. It is noted that there were only minor discrepancies between witness statements, which include those received from many of Mr. George's family members and friends, as well as those of the involved RCMP members. In addition, the witness statements are generally consistent with the physical evidence. A list of the primary RCMP members involved in the incident can be found at Appendix D. Overall, the Commission finds that there is little dispute over what transpired over the course of the four days leading up to and including the shooting death of Mr. George.

Background

[11] Valeri George was a German- and Russian-speaking immigrant from Kazakhstan. He lived with his wife, Irina George, and eleven children on a secluded farm in the area of Buick Creek, near Fort St. John, British Columbia. Another child was married and lived away from home. According to Mrs. George, the family had been in Canada for four years. Mr. George had difficulty with English, which made working difficult. He spoke of going back to Germany, but Mrs. George told him that she liked it better in Canada. Mrs. George indicated that they had a good relationship and that Mr. George was good to their children.

[12] On September 26, 2009, Jack Thiessen reported the following events to the RCMP: Mr. George's family were on their way to Dawson Creek when he chased after them in a separate vehicle. Mr. George allegedly used his vehicle to force the vehicle his family was in to stop. Mr. George subsequently used a rifle to shoot out two of the tires and demanded that his family return home. The driver of the vehicle (a family friend) was able to drive away while the tires were deflating and pulled into a neighbour's residence, which was also the home of Mr. George's cousin, Jakob George. Mr. George followed them, shot out the other two tires of the vehicle and again demanded that his family return home. Mr. George left and returned to the property several times before going home. The family proceeded to Dawson Creek in a different vehicle and Mr. Thiessen, who arrived at Jakob George's property during the incident, called the RCMP to report the matter.

[13] The following details of those events are as recounted by those present, which included Mrs. George and several of the George children, members of the Simon family (who were driving the George family to Dawson Creek), Rudi, Jakob and Paul George (who lived at the home where the George family sought refuge after the van tires were disabled), and Jack Thiessen, the neighbour who made the report to the RCMP.

[14] According to all involved, Mr. George did not want to go to the wedding in Dawson Creek but gave permission for Mrs. George and the children to go and to be driven by the Simon family. Multiple witnesses confirmed that Mr. George had given his permission. The Simon family reported that on September 26, 2009, at approximately 9 a.m. they drove up the driveway to the George residence and left the gate open as they picked up the George family. When they went to leave the property with Mrs. George and the children, they discovered that the gate had been shut, presumably by Mr. George. One of the George children got out of the vehicle and opened the gate, and they went on their way to the wedding.

[15] Not long after leaving the George property, Mr. George drove up behind them in his own vehicle, passed them and cut them off, forcing them to stop their vehicle. Mr. George got out of his vehicle carrying a rifle and spoke with the driver of the van—Johan Simon. Mr. George asked him where he was going with his family. Mr. Simon told him that they were going to the wedding. Mr. George asked him for the keys to the vehicle, and Mr. Simon asked him, "What, what do you want?" Mr. George proceeded to shoot two of the tires on the vehicle, apparently in an attempt to keep the family from going, but the tires were only slowly deflating and they were able to make it to Jakob George's property, which was two or three kilometres away. According to Mrs. George, it appeared at first that Mr. George was heading home. She stated that Mr. George thought they were not going to keep driving, but the tires were not completely flat yet and they drove on. Mr. George then turned around and followed them to Jakob George's property.

[16] After stopping at the neighbouring property, Mr. George got out and shot out the remaining two tires on the vehicle being driven by Mr. Simon. Mr. Simon approached Mr. George, who asked him if he wanted to fight. Mr. Simon replied that he did not and asked Mr. George to calm down. Mr. Simon noted that he had never seen Mr. George like this before. Several persons who were present reported that Mrs. George and the children were shaken up and wanted to come inside the house, which they did. Mr. George was clearly upset and agitated. He came and went from Jakob George's property a number of times and it was reported that at one point while Mr. George was arguing about the return of his family, he held a butter knife in his hand.

[17] Mr. Thiessen, who knew Mr. George but had difficulty communicating with him due to language issues, stopped at Jakob George's at some point after the first time Mr. George had left the property. Mr. Thiessen observed that the four tires were flat on a large van (the vehicle that had been carrying the Simon and George families) when he approached the house. Jakob George told him that Mr. George had shot out the tires. During this conversation, Mr. George returned and was very agitated. Through an interpreter (Jakob George's sons), Mr. George told him that a family had come and stolen his family and that he had to go and save them. Mr. Thiessen told Mr. George that he understood being upset if someone came and stole his family, but shooting the tires out a vehicle was not the way to go about getting his family back. Mr. Thiessen also told him that unless he settled down and changed his way, he would be calling the RCMP. Mr. George immediately responded that if he called the RCMP, he would be joining the enemy and that Mr. Thiessen and his whole family would go to hell. Mr. George then got in his vehicle and drove away.

[18] Mr. Thiessen further stated that Mr. George returned five minutes later. While Mr. George was speaking with Jakob George, Mr. Thiessen did a quick search of Mr. George's vehicle for the firearm, but did not find it. When Mr. George saw what he was doing, Mr. George got angry and brought his fist up to Mr. Thiessen, who pushed it away. They exchanged some words before Mr. George left again.

[19] Mr. Thiessen went inside the house with the George family. While they were inside, Mr. George returned and attempted to get inside, but the door was locked. According to Mr. Thiessen, Mr. George was seen looking in all the windows and the children attempted to move out of his line of sight. Mr. Thiessen stated that all of the women in the house were clearly very upset. Jakob George went to the door and Mr. George came inside as the family went upstairs. Mr. Thiessen remained on the stairs and prevented Mr. George from going up. Mr. George was clearly agitated, yelling and swearing in a loud voice. Mr. George spoke with Mr. Simon and reportedly told him that he had stolen his family, that they needed to come home immediately and had not asked to go to the wedding. He subsequently left again.

[20] In the meantime, another friend had arrived with an alternate vehicle for the Simon and George families to take to the wedding, and they left in it. Mr. Thiessen drove behind them as far as Buick to ensure that they were okay before telephoning the RCMP to report the incident.

[21] Mr. Thiessen later reported that he was told by those translating for him (members of Jakob George's family who were present at the time) that Mr. George said that there would be consequences to pay for his family having just run off. He read the situation as very tense and possibly dangerous, so he decided to call the RCMP. When Mrs. George left with the children, he cautioned her not to come back until the situation had been sorted out.

Initial involvement of the RCMP

[22] Mr. Thiessen reported the following information in his initial call to the RCMP: He wanted to speak with someone about a family issue involving a neighbour. The wife and children wanted to go to a wedding but the husband did not feel like taking them. Another family picked them up to take them, but the husband "got very violent and, and he took his .22 out and he was shooting." The incident had happened about two hours previously, and Mr. Thiessen did not witness the shooting but saw bullet holes in the tires and a few bullets that Mr. George had dropped on the ground, which he picked up. Mr. Thiessen stated to the dispatcher: "[H]e kept coming to the house there and he got very violent and he was going to beat me up. Because I went through his vehicle, I was gonna confiscate that rifle if I could find it . . . ." They finally got the family out of there and to where Mr. George would not locate them. Mr. Thiessen reported that Mr. George did not speak English, so the RCMP would need an interpreter.

[23] Records indicate that that information was relayed to Constable Krystal Moren of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment within minutes of Mr. Thiessen's call. Constable Moren spoke with Mr. Thiessen by telephone and noted some of the following:

- He had called to report a domestic dispute involving Mr. George and his wife, during which time Mr. George shot out the tires to a vehicle when she was trying to leave.

- Mrs. George and her children were currently safe and in Dawson Creek.

- A friend had picked up Mrs. George and her children to drive them to a wedding and Mr. George became upset and followed them, eventually shooting out all four tires of the vehicle they had been travelling in.

- Mrs. George and the children sought refuge in a neighbour's house, where Mr. Thiessen became involved and spoke with Mr. George.

- Mrs. George and the children were able to leave in another vehicle.

- The George children were scared and crying.

- Mrs. George did not want him to call the police and was worried that Mr. George may go to jail.

- Mr. George did not speak English.

- Mr. Thiessen was scared of what may happen to Mrs. George when he returned home.

- Mr. Thiessen indicated that there are reports of domestic violence between Mr. George and his wife but that the community will not say anything to the police.

- Mr. Thiessen checked Mr. George's vehicle for the firearm but could not locate it.

- Mr. Thiessen agreed to meet Constable Moren and Constable Josh Martyn at Jakob George's house.

[24] Constable Moren and Constable Martyn arrived at Jakob George's house mid-afternoon on September 26, 2009, and learned the following (with the assistance of a family friend, Jakob Dick, translating when necessary):

- At approximately 9 a.m. that morning he was awoken by the arrival of Johan Simon pulling into his driveway with Mrs. George and her children.

- Mr. George had shot out the tires of the vehicle that was driven by Mr. Simon and he could hear the air leaking from the tires.

- Mr. George was upset that his wife was leaving when he told her not to.

- Mr. George was waving the gun around but he did not threaten anyone or point the firearm at anyone.

- Mr. George left his house, and Mrs. George and the children were able to leave.

- Mr. George sometimes acts strange, but he has never seen him behave this way.

- Mr. George will not listen to anyone.

[25] During that time, Mr. Thiessen provided the members with several bullets he had picked up on the ground, purportedly dropped by Mr. George. After speaking, Mr. Thiessen and Mr. Dick agreed to help the members in getting Mr. George to agree to speak with them. The approach taken by the members was to tell him that he would not be arrested at this time, but they wanted to speak with him and retrieve the firearm. Constable Moren noted in her report that it was not known whether Mr. George would shoot at members upon seeing them, as he may think he was about to be arrested.

[26] When the members attended Mr. George's address, they discovered that the metal gates were locked from the inside. Telephone calls to the residence went unanswered. Mr. Thiessen and Mr. Dick were not concerned that Mr. George would harm himself at that time, and Mr. Thiessen indicated that the gate is never locked and took it to mean that he did not wish to speak with anyone. They all returned to Jakob George's residence, where Mr. Dick was able to speak with Mrs. George by telephone. Mrs. George stated that they would stay in Dawson Creek and would speak to the local RCMP at her daughter's house about the incident. She stated that she suspected that Mr. George was home and had locked the gate.

[27] Later that evening, Constable Moren spoke to Mr. Thiessen, who told her that Mr. George returned to Jakob George's residence after the members had left. He seemed to have calmed down but was still upset that his wife had left for the wedding against his wishes. Mr. Thiessen told her that he thought Mr. George would "deal" with his wife when she returned home, and that Mr. Thiessen had urged her not to return home. Mr. Thiessen relayed his belief that this was not Mr. George's first act of violence towards his wife.

[28] That same evening, members of the Dawson Creek RCMP Detachment obtained statements from Mrs. George and the Georges' eldest daughter. A decision was made that Mr. George could be dealt with the next day, as the rest of the George family was safe for the night. The situation would be reassessed the following day.

[29] On September 27, 2009, members confirmed that the George family remained in a safe location, but the members were busy for much of the day on other calls. That evening, members obtained further information from the family by telephone, and from members of the community. They learned that the previous evening, the neighbour who had originally given Mr. George the firearm had heard about the incident and attempted to get it back from Mr. George. However, Mr. George told him that the rifle was now in Wonowon. That was believed to be a lie, as the person Mr. George claimed he had given the rifle to was in Dawson Creek at the wedding being attended by the George family. No one saw Mr. George on this day. A recorded statement was taken from Mr. Thiessen and the owner of the rifle.

[30] In the early morning hours of September 28, 2009, a pass-on request was prepared with the following instructions:

- Locate a German translator that will be able to speak with Mr. George by telephone. Mr. George needs to know that he will be arrested for the shooting of the tires incident and that he needs to cooperate and not be nervous.

- Locate and arrest Mr. George for careless use of a firearm and mischief. If Mr. George is cooperative, obtain the firearm.

(Note: a caution was added outlining some information about Mr. George, including that he believes that police are extremely corrupt and may feel that they are a strong threat against him. He may be dealing with an undiagnosed mental illness and his behaviour may escalate, as his wife had not returned home. It was unknown whether he would fire at or run from police. He may also barricade himself inside his house to avoid arrest, as he may believe he is going to jail for a long time. Mr. George is in possession of a .22 single shot rifle.)

- Update Mrs. George on the situation (through a family member) and ensure that she does not return home.

[31] A German-speaking member at the Castlegar RCMP Detachment—Constable Dirk Finkensiep—was identified and engaged to speak with Mr. George by telephone. Constable Finkensiep spoke with Mr. George, after first speaking with Mrs. George that evening. Earlier that afternoon, members began surveillance of the George property to keep track of Mr. George's whereabouts, as well as to be in a position to receive him should Constable Finkensiep be able to convince Mr. George to surrender to police. Unfortunately, Mr. George refused to engage with Constable Finkensiep and would not answer his subsequent calls. Constable Finkensiep also engaged the assistance of a church elder and friend of Mr. George's, but without success. Members remained at the property, but were instructed to observe only and to not attempt to stop the vehicle or confront Mr. George if he was to leave.

[32] On September 29, 2009, Constable Finkensiep continued to work with the church elder and friend to facilitate communications with Mr. George. Mr. George continued to refuse to speak with police and wanted his family returned to him. It was reported by the friend that Mr. George knew that what he did was wrong and was afraid of what would happen to him. Constable Finkensiep attempted to contact Mr. George again, but his calls went unanswered.

[33] In the later afternoon of September 29, 2009, members observed a white van approach the end of Mr. George's driveway (coming from the residence, which was not in sight of their location). Once the driver of the van saw the marked police vehicle, the driver retreated. At this point, the NDERT had been activated and were on their way to Fort St. John.

Mr. George's state of mind

[34] It became evident in the hours and days following the initial incident that Mr. George's behaviour was out of character for him, although not the first time he displayed strange behaviour over the previous months. Almost every person who spoke with the RCMP about Mr. George expressed some concern about his mental state. On the day of the incident, one witness reported that Mr. George told him that the President of Russia had come to his house. Mr. George spoke to a number of people by telephone, expressing concern about the whereabouts of his family, seemingly convinced that the police had taken them.

[35] Mrs. George stated that she had wanted to return home, but the police had told her to stay away and not to call her husband. Her family members also did not want her to go back. She stated that her family thought that the police would talk to Mr. George and that he would see a doctor. Mrs. George reported that her husband was always afraid of the police and doctors.

The George family property

[36] After September 26, 2009, Mr. George remained at his family property, pictured below. As noted above, the house is accessed by way of a gated driveway and is some distance from the road. The remoteness of the location presented a number of challenges for members in terms of negotiating with Mr. George as well as being able to approach him in order to facilitate his arrest.

Photo 1: Showing the George residence, outbuilding and farm area.

Photo 2: Showing a larger portion of the George property, including the residence, outbuildings, farm area and lagoon.

Photo 3: Aerial photograph of the George property, including all buildings and the driveway leading out to the main road.

North District Emergency Response Team activation and deployment

[37] Since efforts to persuade Mr. George to cooperate with the police were unsuccessful and he remained armed and emotionally unpredictable, the NDERT was activated on September 29, 2009. The following NDERT team members were ultimately deployed:

- Inspector Patrick Egan – Incident CommanderFootnote 3

- Corporal Richard Brown – NDERT Team LeaderFootnote 4

- Corporal Ryan Arnold – NDERT second in command

- Constable Colin Warwick – NDERT Member and Police Dog Service

- Constable Matthew Shaw – NDERT Member

- Constable Martin Degen – NDERT Member

- Constable Brian Merriman – NDERT Member

- Constable Colin Atkinson – NDERT Member

- Constable Nathan Poyzer – SpareFootnote 5

[38] They were supported by the following members:

- Sergeant Mike Stevenson – Negotiator

- Corporal Claudette Garcia – Negotiator

- Ryan Schaefer – Radio technician

- Civilian Member Shirley Hogan – ScribeFootnote 6

- Civilian Member Don McKelvie – Dispatcher

- Civilian Member Nicholas Chapman – Dispatcher trainee

- Civilian Member Greg Melson – Radio technician

[39] Upon arrival of the team, a member covertly entered the George family property on foot and to a position where he could observe the residence and monitor the movements of Mr. George and anyone else on the property. The member relayed that information to the Incident Commander and other team members by radio. Throughout the morning, Mr. George was seen entering and exiting his residence with the rifle, and later entering a white van with the rifle and driving it up the driveway at a high rate of speed, with music blaring. He returned the vehicle to the residence and he went back inside, still holding the rifle. He later returned to his vehicle and drove it erratically and at a high rate of speed about the property. Mr. George was also observed walking around with the rifle, aiming it randomly at different points in the bush.

[40] Each time Mr. George was reported to be inside his residence, members of the Crisis Negotiation Team (CNT) attempted to make contact by telephone. One call was answered but immediately disconnected; the rest went unanswered. (Investigators later discovered that Mr. George had apparently unplugged the telephone from the wall.)

[41] NDERT members contained the end of the driveway in an attempt to prevent Mr. George from leaving the property. At one point, Mr. George was observed loading the rifle and walking up the driveway with his four dogs. Members were instructed by Inspector Egan to verbally challenge Mr. George. Mr. George was given commands in German to halt, but he ignored the commands and continued walking back and forth with the dogs, yelling. He then walked back in the direction of his residence.

[42] Following this encounter, members moved their position and the barricade to the area of the gate, which was some distance from the road. The NDERT positioned another vehicle outside the gate to help fortify their blockade. Mr. George was observed fuelling his white van; he then retrieved his rifle from the van and went back into his residence.

[43] Mr. George was subsequently observed exiting his residence carrying the rifle. He started an all-terrain vehicle (ATV), but it stalled. He then entered the white van, still carrying the rifle, and drove it down the driveway at a high rate of speed toward NDERT members. As he neared the gate, members fired at the van. The van came to a stop and Mr. George exited it, carrying the rifle. More shots were fired by NDERT members and Mr. George collapsed on the driveway. Members approached and began providing first aid. An ambulance attended and efforts continued; however, Mr. George was ultimately pronounced dead at the scene. Mr. George received four gunshot wounds, two of which penetrated the chest and lead to massive internal bleeding, causing his death.

Analysis of the RCMP's Involvement with Mr. George from September 26 to 30, 2009

As noted above, the issues to be examined by the Chair-initiated complaint are:

- whether the RCMP members or other persons appointed or employed under the authority of the RCMP Act involved in the events of September 26 to September 30, 2009, from the moment of initial contact through to the subsequent death of Valeri George complied with all appropriate training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements relating to the use of force; and

- whether the RCMP's national-, divisional- and detachment-level policies, procedures and guidelines applicable to such an incident and to situations in which RCMP Emergency Response Teams are deployed are adequate.

In its response to the Chair-initiated complaint, the RCMP indicated that it was satisfied with the conduct of its members, and that the applicable policies, procedures and guidelines were adequate. The RCMP's response to recommendations made as a result of the B.C. Coroner's inquest and the RCMP's IOR are referenced where applicable to the Commission's examination of the issue.

Conduct of RCMP members prior to the activation of the NDERT

a) Initial response and investigation

[44] The police (including the RCMP) have a duty to investigate a complaint of criminal activity when there is a reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. Paragraph 18(a) of the RCMP Act states that it is the duty of members:

18(a) to perform all duties that are assigned to peace officers in relation to the preservation of the peace, the prevention of crime and of offences against the laws of Canada and the laws in force in any province in which they may be employed, and the apprehension of criminals and offenders and others who may be lawfully taken into custody.

[45] In addition, RCMP policy dictates that all complaints of violence in relationships must be investigated and documented.Footnote 7 Members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment were duty-bound to investigate the call received from Mr. Thiessen regarding the actions of Mr. George against his family members.

[46] Members spoke with Mr. Thiessen and others present during the incident and determined that Mrs. George and her children were safe and out of town. Members used family members or friends where needed as interpreters. Mr. Thiessen and the others agreed to assist with making attempts to speak with Mr. George, although their calls to his residence went unanswered. Members spoke with Mrs. George by telephone, who stated that she would remain out of town until the matter was resolved. Arrangements were made for Mrs. George and one of her older daughters to give statements to a member of the Dawson Creek RCMP Detachment.

[47] When members initially met with Mr. Thiessen, he turned over two unfired bullets that Mr. George had apparently dropped in the yard during the incident. The members attended Mr. George's residence, but the metal gates were locked from the inside. No one was concerned that Mr. George would harm himself at that time. Mr. Thiessen told the members that the gate is never locked and that he took it to mean that Mr. George did not wish to speak to anyone.

[48] In the days that followed, and as detailed earlier in this report, members made concerted efforts to gather additional information about Mr. George, his history and his habits, and made numerous attempts to speak directly with him to resolve the situation and facilitate a peaceful arrest. They also took steps to gather additional physical evidence to support the charges and an application for a warrant, when it was determined that that may be necessary.

[49] Inspector Egan, in his capacity as the Officer in Charge of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment, stated that he spoke with Inspector Ray Fast, the Operations Officer from the North District, late on September 28, 2009, regarding his assessment of the situation. They decided that as long as they could place Mr. George at his home and make telephone contact with him (which had been done throughout that day), they would hold off on deploying an ERT. While Mr. George's actions had been troubling, Inspector Egan felt that the situation could be resolved through dialogue, and that it was sufficiently mitigated by the placement of members at the property and the fact that Mrs. George and the children were safe and out of town. He noted that while the situation had the potential to escalate, for the time being Mr. George's family was safe.

[50] In the Commission's view, the members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment who were involved in the initial response and investigation took reasonable steps to investigate the matter and ensure the safety of the George family. It was reasonable for members to determine that, for the time being, Mr. George was not an immediate danger to others as they continued to gather information and physical evidence, as well as monitor the movements of Mr. George. That assessment changed as time passed, and will be discussed later in this report.

Finding: RCMP members were duty-bound to investigate the reported actions of Mr. George.

Finding: RCMP members took reasonable steps to investigate the incident.

Finding: RCMP members took appropriate steps to ensure the safety of Mr. George's family pending an arrest.

b) Grounds to arrest Mr. George

[51] It became evident early on in the investigation of this matter that Mr. George would be arrested due to the seriousness of his reported actions. When evaluating a member's decision to make an arrest and pursue charges,Footnote 8 it is important to keep in mind that his or her role is not to determine a suspect's guilt or innocence—they do not act as judge and jury. The goal of an investigation is to determine whether or not there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence has been committed.

[52] The initial charges that were contemplated by members were for careless use of a firearm and mischief, as confirmed by Constable Moren's pass-on request detailed earlier in this report. Those offences are defined as follows in the Criminal Code of Canada:

86. (1) Every person commits an offence who, without lawful excuse, uses, carries, handles, ships, transports or stores a firearm, a prohibited weapon, a restricted weapon, a prohibited device or any ammunition or prohibited ammunition in a careless manner or without reasonable precautions for the safety of other persons.

430. (1) Every one commits mischief who wilfully

(a) destroys or damages property;

(b) renders property dangerous, useless, inoperative or ineffective;

(c) obstructs, interrupts or interferes with the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property; or

(d) obstructs, interrupts or interferes with any person in the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property.

430. (2) Every one who commits mischief that causes actual danger to life is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for life.

[53] In the Commission's view, there was overwhelming evidence supporting the above-noted charges against Mr. George in relation to the shooting incident. There were numerous witnesses to Mr. George's actions and they made consistent statements to investigators that were supported by physical evidence. In addition, there were no denials on the part of Mr. George when he discussed the incident with family and friends. In the Commission's view, it is clear that members had reasonable grounds to believe that multiple offences had been committed by Mr. George.

[54] However, even in situations where police have reasonable grounds to believe that an individual has committed an offence, an arrest does not automatically follow. The decision to make an arrest without a warrant involves consideration of the requirements listed under section 495 of the Criminal Code and the exercise of discretion.

[55] When a person is believed to have committed an indictable offence, such as that set out in subsection 430(2) of the Criminal Code (mentioned above), he or she may be arrested without a warrant. There are no additional requirements set out in the Criminal Code. When a person has committed what is known as a hybrid offence—i.e. where the prosecution may elect to proceed by indictment or summary conviction, and as provided for in section 86 of the Criminal Code—a police officer may arrest that person without a warrant to:

- (i) establish the identity of the person;

- (ii) secure or preserve evidence of or relating to the offence; or

- (iii) prevent the continuation or repetition of the offence or the commission of another offence.Footnote 9

[56] Members were clearly concerned about a repetition of the offence or the commission of another offence against Mrs. George or other members of the George family. According to Mrs. George, both RCMP members and members of her family did not want her to return to her residence until the matter was resolved. Friends of the George family expressed concern to members about what could happen when Mrs. George returned. In the Commission's view, members reasonably believed it was necessary to arrest Mr. George for the safety of his family and satisfied the requirement set out under section 495 of the Criminal Code.

[57] That being said, section 495 of the Criminal Code is permissive. It does not require the police to make an arrest simply on the basis that someone is believed to have committed an offence. The power of arrest is a discretionary one. It is the nature of discretion that different people will exercise their discretion differently in similar circumstances. It allows a police officer to make decisions based on an assessment of the circumstances at the time that they occur and within a range of acceptable outcomes. Accordingly, decisions involving the exercise of discretion are entitled to some level of deference.

[58] Those decisions are made based on the individual circumstances of each case. However, there are also policy considerations, particularly in cases involving domestic violence. RCMP policy stresses the importance of victim safety and that police intervention and action should address that.Footnote 10 It also refers to the B.C. Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General's policy on violence against women in relationships and its emphasis on a proactive arrest and charges where grounds exist.Footnote 11 Mrs. George and her family remained away from their home due to the perceived danger. Victim safety is of the utmost importance when considering whether or not to exercise discretion to arrest or not to arrest. In all the circumstances, the Commission is satisfied that the decision to arrest Mr. George without a warrant was reasonable.

Finding: RCMP members had reasonable grounds to believe that Mr. George had committed multiple Criminal Code offences.

Finding: RCMP members had grounds to arrest Mr. George without a warrant following the incident with his family.

Finding: RCMP members' decision to pursue Mr. George's arrest without a warrant was a reasonable exercise of discretion.

c) Application for a warrant

[59] As the days passed without an arrest, members decided that a warrant to arrest Mr. George in his home (known as a Feeney warrant) may be necessary. On September 29, 2009, members sought and obtained a Feeney warrant for the following Criminal Code offences:

- mischief endangering life (subsection 430(2));

- use of a firearm while committing an offence (paragraph 85(1)(a));

- dangerous operation of a motor vehicle (subsection 249(1)); possession of a weapon for a dangerous purpose (section 88);

- possession of a firearm without a licence (subsection 92(1)); and

- intimidation through the use of violence (subsection 423(1)).

[60] The warrant was issued by a Judicial Justice of the Peace for the Province of British Columbia on September 30, 2009, at 12:50 a.m. It authorized police to enter Mr. George's residence for the purpose of arresting him, without prior announcement. The time period given for executing the warrant was from 7 a.m. on September 30, 2009, until 23:59 p.m. on October 2, 2009.

[61] The role of the Commission is not to assess the validity of the warrant, as it was issued by the court, which determined that the application for the warrant set out reasonable grounds to believe that the above-noted offences had been committed. The decisions of the court are not subject to review by the Commission. However, the Commission may assess the actions of RCMP members in relation to the frankness and accuracy of the warrant application in relation to the investigative record as well as the reasonableness of the discretion exercised in deciding to effect the arrest at the time members chose to do so.

[62] The warrant application was completed and submitted to the court by Constable Jessica Veysey. Prior to the warrant application, members had not sought to arrest Mr. George in his home, but rather sought to have Mr. George come to them voluntarily. While that continued to be the goal even after the NDERT was activated and deployed, it was evident that Mr. George may not be cooperative and members may be required to enter his home to effect his arrest. In the Commission's view, it was both reasonable and necessary at that stage of the investigation to seek a Feeney warrant. Having reviewed the contents of the warrant application and the Fort St. John investigation file, the Commission finds that the application contained a reasonably thorough and accurate representation of the evidence up to that point in time.

Finding: It was both reasonable and necessary for members to seek a warrant to arrest Mr. George in his home in the event that negotiations failed.

Finding: The warrant application contained a reasonably thorough and accurate representation of the evidence.

d) Communications

[63] As noted earlier in this report, members did not attempt to approach Mr. George on his property on the basis that a) he had closed and locked the gate (indicating that he would not be receptive to visitors), b) they were told that Mr. George would not react well to the intervention of police, and c) Mr. George had a firearm that he had already used in the commission of a criminal offence. From September 26 to September 28, 2009, members had relied on family and friends to communicate with Mr. George and to attempt to facilitate a surrender to police.

[64] Communications were complicated by the fact that Mr. George did not speak or understand English. Members attempted to retain the services of a translator to assist in communicating with Mr. George; however, they were unsuccessful in doing so. On September 28, 2009, Constable Finkensiep of the Castlegar RCMP Detachment was identified as German-speaking and was asked to assist.

[65] Constable Finkensiep first spoke by telephone with Mrs. George to ensure that he was able to communicate with her and would be able to communicate with Mr. George, and to gather more information about Mr. George. He was provided with a two-page questionnaire by members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment, which he used when speaking with Mrs. George. That conversation was audio-recorded and formed part of the investigative record.

[66] At approximately 6:30 p.m. on September 28, 2009, Constable Finkensiep subsequently called the George residence and spoke to a male who identified himself as Mr. George. Constable Finkensiep attempted to speak to Mr. George about what had transpired and about surrendering to the police, but Mr. George said that he did not want to talk to the police and hung up the telephone. Mr. George did not answer subsequent calls from Constable Finkensiep. That conversation was also audio-recorded. At the time of the call, members were positioned at the end of Mr. George's driveway in order to receive him should he be willing to surrender.

[67] Members enlisted the assistance of Jakob Remple Sr., a friend of Mr. George and a respected church elder in their community. Mr. Remple Sr. had been in contact with Mr. George in the days following the incident. When reached by telephone by Mr. Remple on September 29, 2009, Mr. George told him that he would not speak to the police, would not present himself to the police, and demanded that his family be returned. Mr. George admitted to damaging the tires and said that he would pay for them, but he was scared of what would happen with the police.

[68] In the morning of September 29, 2009, Constable Finkensiep again enlisted the assistance of Mr. Remple Sr. Mr. Rempel Sr. was asked to call Mr. George. Constable Finkensiep asked him to tell Mr. George to talk to the police, as they wanted the situation resolved, and that it would not just go away. Mr. Remple Sr. stated that he spoke to Mr. George twice that day. Mr. George continued to refuse to speak with the police and said that he would not speak with the police until his family was returned. When Mr. George told him that the Simons took his wife and children without his permission, Mr. Remple Sr. reminded him that he was a witness to the conversation in which Mr. George agreed that his family could go to the wedding. Mr. Rempel Sr. stated that he told Mr. George that the police were being cautious because he had a gun and that the police wanted him to come out and talk to them. Mr. Remple Sr. tried to convince Mr. George to give himself up to the police and that everything was going to work out peacefully. But Mr. George was convinced that the police were going to harm his family.

[69] Constable Finkensiep made two more attempts to reach Mr. George by telephone, but no answer was received. No further contact was made until after the activation and deployment of the NDERT.

[70] Extensive efforts were made to communicate with Mr. George in a language that he understood. Mr. George's inability to communicate in English presented a challenge, but members took steps to retain the services of an interpreter and used family and friends until they were able to find a German‑speaking member to make that contact. I note that a recommendation was made following the Coroner's inquest that every RCMP detachment determine the predominant second language in their communities and have a local officer fluent in that language. The RCMP stated in its response to the Chair-initiated complaint that that recommendation was not feasible but that other strategies are in place, including the ability to deploy translator/language capability police officers when required, as well as the use of translation services. However, "E" Division Headquarters was considering the creation of a database of members that speak a language other than English.

[71] In addition to the language issues, Mr. George was part of a small community that reportedly preferred to deal with issues internally, and it became evident that Mr. George did not trust the police for cultural reasons. To that end, members used family and friends to facilitate communications, and guidance was provided to those individuals to help facilitate a surrender by Mr. George to police. Matters were further complicated by Mr. George's apparent mental state.

[72] RCMP policy states that members are not qualified to make a diagnosis of mental illness, but should be able to recognize behaviour that indicates signs of one.Footnote 12 It recognizes that clear communication can be effective in de-escalating a situation involving a person who may have a mental illness and suggests that members may seek the assistance of a close friend, family member, religious or spiritual leader, or a mental health professional in appropriate circumstances, and after a careful risk assessment.Footnote 13

[73] Over the course of September 26 to 28, friends and family reported on their conversations with Mr. George, although generally those conversations were not prompted by the RCMP. When it became clear that Mr. George was not receptive to speaking with the RCMP, members attempted contact through a friend and respected church elder. Mr. Remple Sr. had spoken to Mr. George regularly in the days that followed the incident, contact that was first initiated by Mr. George, who was looking for his family. Mr. Remple's son was married to Mr. George's eldest daughter, and Mr. George's family was staying at their home in Dawson Creek. In the Commission's view, it was reasonable for members to seek such assistance from Mr. Remple Sr., and appropriate direction was given with respect to the messages to be conveyed to Mr. George.

[74] According to Inspector Egan's statement, they considered using Mrs. George to make contact with Mr. George. However, that idea was rejected for three reasons: there could be a potential for retribution against Mrs. George for assisting in the arrest should they reconcile; if the approach was unsuccessful, it may cause Mr. George to become more volatile; and it would place Mrs. George in the position of being re-victimized. Inspector Egan stated that at that point it was clear that speaking with Mr. George was going to be difficult and further failed attempts may agitate Mr. George and force a confrontation. Consequently, he decided to consult with Inspector Fast about deploying an ERT. In the Commission's view, Inspector Egan's decision not to approach Mrs. George to make direct contact with her husband was reasonable.

[75] There were early indications that it may be difficult to communicate with Mr. George. His apparent mental state – which included indications of paranoia and delusions - may have contributed to those difficulties. There is much discussion amongst policing agencies regarding the role of mental health professionals and when and how to engage them during incidents of a criminal nature. In the current case, there is no indication that members considered seeking assistance from a mental health professional. While Mr. George had not been diagnosed with a mental illness, it was clear by all accounts that he may be suffering from one and that it had some impact on his current behaviour. The Commission encourages RCMP members to consider the use of mental health professionals early on in an incident and in accordance with the above-noted RCMP policy. Had Mr. George been willing to speak with police, a mental health professional could have offered insight into his behaviour and techniques to assist with negotiating his surrender.

Finding: RCMP members made reasonable attempts to communicate with Mr. George in order to negotiate a peaceful surrender.

Finding: RCMP members took reasonable steps to ensure that they could communicate with Mr. George in a language that he understood.

Finding: RCMP members' decision to seek assistance from Mr. Remple Sr. to communicate with Mr. George after he refused to speak with members was reasonable.

Finding: Inspector Egan reasonably decided that using Mrs. George to contact her husband was inappropriate in the circumstances.

Activation of the NDERT

[76] The lack of progress through ongoing communication attempts with Mr. George led Inspector Egan to consult with Inspector Fast about activating the NDERT. According to RCMP policy, any decision to deploy the ERT is generally the purview of a trained Critical Incident Commander. RCMP policy provides that the Criminal Operations Officer or delegate may activate an ERT under the direction of an Incident Commander.Footnote 14 According to Inspector Egan's notes, at 11:55 a.m. on September 29, 2009, Inspector Fast authorized the use of an ERT and appointed him as the Incident Commander.

[77] At the time of this incident, national RCMP policyFootnote 15 stated that an ERT may be activated to provide tactical armed support to:

- apprehend or neutralize armed/barricaded persons with or without hostages;

- assist in the arrest of suspects or mentally deranged persons; and

- assist with high-risk vehicle take-downs or arrests.

[78] A more recent version of the same policy also includes the conduct of rural surveillance where compromise could result in violence towards police, or when specialized equipment and training are required due to environmental conditions.Footnote 16 ERT members are used in such situations because they have specialized training and equipment. Keeping regular detachment members involved in what are essentially prolonged stand-offs can also put a strain on local police resources.

[79] Inspector Egan stated that after receiving an update in the morning of September 29, 2009, it was clear to him that talking to Mr. George was going to prove difficult and that further failed attempts would agitate him and force a confrontation. It was on that basis that he consulted with Inspector Fast about deploying the ERT, and the decision was made. Despite best efforts, members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment were having no success in gaining cooperation from Mr. George, and a confrontation was likely if communications continued to be unsuccessful. In the Commission's view, the decision to activate the NDERT to assist in the arrest of Mr. George was reasonable and consistent with RCMP policy. At the time, Mr. George remained at his residence but continued to pose a threat to his family, and his apprehension was necessary to ensure their safety.

Finding: The decision made on September 29, 2009, to activate and deploy the NDERT to facilitate the arrest of Mr. George was reasonably based and consistent with RCMP policy.

NDERT personnel

[80] The NDERT is a part-time ERT, which means that members of the team have full-time positions within the RCMP separate and apart from their participation with the ERT. As of the date of this incident, all positions on the team were on a voluntary, part-time basis. Part-time team members are subject to the same qualification and training requirements as full-time team members, and RCMP policy provides that an ERT activation supersedes their other duties.Footnote 17 In September 2009, the position of Team Leader was a part-time position occupied by Corporal Richard Brown of the Fort St. James RCMP Detachment. In 2014, the position of Team Leader was made full-time and was occupied by Corporal Ryan Arnold, who was the second in command during this incident.

[81] NDERT members are posted to detachments throughout the North District with equipment stored in Prince George, which is approximately six hours away from Fort St. John. The Fort St. John RCMP Detachment responds to calls from Buick Creek, which is an additional 70 kilometres north.

[82] According to the RCMP's response to the Commission's complaint, all members of the NDERT who were deployed during this incident were found to be current with respect to their ERT training and annual firearms qualifications. As noted above, Constable Poyzer was a spare and was not used in an operational capacity as part of the NDERT, as he had not yet received the required training. Constable Colin Warwick, who was an NDERT member as well as a Police Dog Services member, was also current with respect to his Police Dog Services training.

[83] The members of the Crisis Negotiation Team were also current with respect to their training, except that Corporal Garcia had not completed a refresher course, which was required, pursuant to RCMP policy, in five-year intervals. No reason was provided by the RCMP as to why a refresher course had not been completed at the time. It was noted that Corporal Garcia had considerable experience as a crisis negotiator and had attended numerous related seminars and workshops, particularly with respect to issues related to mental health.

[84] Inspector Egan had completed the Incident Commander's Course previously offered through the Canadian Police College, which had since been replaced by another course that he had not taken at the time of the incident. However, the RCMP noted that Inspector Egan and all Critical Incident Commanders within the North District are now trained to the current standard. Inspector Egan had participated in an ERT training scenario in the preceding six months, in compliance with the Incident Commander policy.

[85] The RCMP acknowledged that the scribe used during this incident was not formally trained as a scribe, but pointed out that there was no formal course required prior to September 2009. Inspector Egan noted during the criminal investigation that, following the incident, he raised concerns about the deficiencies of the notes, only then learning that the member in question had not attended a scribe training course. It is noted, however, that the policy requiring scribes to have completed formal scribe training did not come into effect until several months after this incident. Current policy now requires that scribes be accredited, which includes successfully completing one of three course options that are specific to scribes.Footnote 18

Finding: The NDERT members who were deployed during this incident were current with respect to their training.

Finding: Corporal Garcia had not participated in a negotiators refresher course, as required by RCMP directives.

Recommendation: That the RCMP take steps to ensure that all members who are engaged in critical incidents in any capacity are up‑to‑date with their ongoing training requirements.

Finding: While not required at the time, Inspector Egan had not been trained on the current course standard for Incident Commanders.

Recommendation: That the RCMP ensure that all NDERT members, Incident Commanders, and other supporting personnel receive training on new standards in a timely manner.

Finding: The scribe assigned to the Incident Commander had not taken a scribe's course, although none had been required at the time. Current policy now mandates such training.

NDERT briefing

[86] Prior to the activation of the NDERT, but in anticipation of an activation, Team Leader Corporal Brown spoke with Constable Camil Coutney of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment. Constable Coutney provided some details of the situation and asked what the NDERT would expect from the detachment members should they be activated. Corporal Brown indicated that they "would require a photograph of the suspect, information about his criminal convictions and current charges, maps of the area such a[s] Google Earth, blue prints of the suspect residence, and information about dogs and other animals on the scene."

[87] Following the NDERT's activation on September 29, 2009, and prior to departing Prince George with the rest of the team, Corporal Brown again spoke with Constable Coutney, who indicated that they had gathered maps, pictures and video of the area. Corporal Brown requested that blueprints be obtained. Corporal Brown's notes indicate that he asked Constable Coutney about the presence of dogs, vehicles, and trails leading off the property.

[88] The NDERT left Prince George at approximately 2:45 p.m. on September 29, 2009, and arrived in Fort St. John at approximately 8 p.m. A briefing was conducted shortly thereafter and lasted just under one hour. It was conducted by members of the Fort St. John General Investigation Section who had been investigating the incident. During the briefing, ERT members were provided a photograph of Mr. George, a written summary of events up to that point, a map of the property, and a printout of the forecasted weather conditions. In addition, Constable Coutney provided photographs and video of the property.

[89] According to the statements and notes of the NDERT members, the briefing included information about the alleged offences committed by Mr. George and Mr. George's mental state (including the belief that he had experienced hallucinations, such as seeing the Russian President as well as wolves and black panthers in his backyard), as well as information that Mr. George had been taking his child's medication because he did not trust the doctors; that friends had attempted to facilitate a surrender; that contact with Mr. George by a German-speaking member was unsuccessful; and that he refused to speak with police and demanded the return of his family. Neighbours reportedly said that Mr. George would either flee or battle with police. A member conducting scene security reportedly observed Mr. George's van travel toward him on the driveway, stop at the sight of the police vehicle and turn back in the direction of the residence. Members also spoke about the dogs on the property, previous military experience, religious beliefs, Mr. George's distrust of the police, and his language skills. They also discussed the type of firearm believed to be in Mr. George's possession, which was a .22 calibre lever action rifle.

[90] Having fully considered the results of the Fort St. John members' investigation and all records relating to the briefing, the Commission finds that the briefing was reasonably thorough and accurate. Efforts were made well in advance by members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment to ensure that NDERT members were well-informed and up-to-date on the initial incident involving Mr. George, the events that followed, and additional intelligence that investigators had gathered with respect to Mr. George, his habits and his behaviours.

Finding: The NDERT briefing prepared and given by members of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment was reasonably thorough and accurate.

NDERT deployment

[91] RCMP policy provides that only an Incident Commander can deploy an ERT and authorize use of force.Footnote 19 The onus and responsibilities placed on an Incident Commander at a critical incident are onerous and wide-reaching. To meet these demands, the RCMP selects, trains and mentors Incident Commanders in order to provide them with the knowledge, skills and expertise necessary. At the time of this incident, Inspector Egan was the Officer in Charge of the Fort St. John RCMP Detachment. He had been involved in a number of successfully resolved ERT call outs, including one a year prior involving a chronic alcoholic and schizophrenic who was in possession of a rifle and had fired shots at detachment personnel.

[92] While the NDERT was activated on September 29, 2009, it was not deployed to Mr. George's location until the following morning. When considering whether to deploy the team in the evening of September 29, 2009, or starting in the morning of September 30, 2009, Inspector Egan decided on the latter for the following reasons:

- He felt that it would be safer to deploy during daylight, given that the members were unfamiliar with the local environment.

- He expected that they would be there for a long period of time, and the NDERT and support staff had driven for six hours in bad weather to get to Fort St. John. He felt that it would be better if they were well rested.

- He and NDERT Team Leader, Corporal Brown, agreed that the plan would be one of containment and negotiation, which had been a successful approach in another intervention earlier that year and involving many of the same personnel.

[93] There was no indication that Mr. George would leave his residence during the night, and members were placed at the perimeter in case he did. Inspector Egan reasonably believed, at the time, that negotiations would be prolonged and that NDERT members may be there for a long period of time once deployed to the George property. Consequently, having considered the risks involved, and in all the circumstances, the decision to wait until the morning to deploy the NDERT to the George property was reasonable.

Finding: Inspector Egan's decision to delay deploying NDERT to the George property until the early morning of September 30, 2009, was reasonable in the circumstances.

Operational plan

[94] The RCMP's Tactical Operations Manual provides that unless exigent circumstances exist, the ERT Team Leader is responsible for ensuring that written operational plans are completed as soon as possible at a deployment and are approved and initialed by the Incident Commander before being carried out.Footnote 20

[95] Corporal Brown's statement indicates that following the briefing, he discussed preparation of the operational plan with the Incident Commander, Inspector Egan, and told him that his proposed plan would be to take the situation slowly and rely on negotiation to safely resolve it. Inspector Egan agreed and told him that they could wait out the situation "for quite a while." Corporal Brown spent time with the other NDERT members discussing tactics and logistics, and watching the video of the scene.

[96] Later that night, Corporal Brown wrote out the operational plan. It provided for basic containment, including an ERT member (Constable Shaw) entering the property covertly to gather information on the property and Mr. George's activities (so that they could react accordingly), with a PDS/NDERT member (Constable Warwick) providing cover on the back of the house. Using a family friend as an interpreter, the plan was to focus on negotiation.

[97] Records confirm that the operational plans were completed by Corporal Brown and signed by Inspector Egan, as required by RCMP policy. The "objective" of the plan was to "peacefully resolve the situation through negotiation prior to any deliberate action." The surrender plan included having negotiators, through a family friend/interpreter, instruct Mr. George by telephone on what to do and a German-speaking NDERT member (Constable Degen) giving commands onsite so that NDERT members could safely arrest him. If Mr. George escaped by foot, members would confront him, instruct him to stop, and use appropriate intervention options (as per their training).

[98] In anticipation of an escape by vehicle, the plan was to block the driveway. The quad trail would be covered but not physically blocked. Additional plans were made in the event that Mr. George became aware of members on his property and if he barricaded himself in his residence. All plans were presented to the ERT members on the morning of September 30, 2009, after being provided with a copy of a signed Feeney warrant for Mr. George's residence.

[99] The Commission notes that while the escape option plan provided for a barricade at the driveway should Mr. George escape by vehicle, no additional plan was made in the event that Mr. George breached the barricade. Prior to establishing the barricade, which eventually changed locations on the driveway and is discussed later in this report, it was likely anticipated that Mr. George would not be able to breach it. In the Commission's view, that was a reasonable assessment based on what was known at the time of planning. It was not known that Mr. George would in fact repeatedly attempt to leave the property despite the police presence, given his previous retreat upon seeing a police vehicle, and would do so with his firearm. (Following Mr. George's shooting and in their statements to investigators, NDERT members provided different opinions with respect to whether or not they thought the barricade, as it existed at the time of the shooting, could be easily breached. The sufficiency of the barricade will be addressed in a later section.)

Finding: The operational plans were prepared and signed by the Team Leader and Incident Commander prior to the NDERT's deployment at the George property, in accordance with RCMP policy.

Finding: The operation plans were reasonably thorough and appropriate in the circumstances known to members at the time they were developed.

Observation of Mr. George

[100] At approximately 9 a.m. on September 30, 2009, Constable Shaw and Corporal Arnold entered the property on foot in order to set up in an observation position near the George residence, which took approximately one hour. Constable Shaw indicated in his written statement to investigators that he set up in a position approximately 70 metres from the north side of the George residence and was able to observe a number of vehicles, the residence and the outbuildings. He was not able to observe the main entrance in and out of the residence but could see onto the deck off of the main entrance and into the residence through a large picture window on the north side. From this position, Constable Shaw provided commentary about the property and buildings to the ERT, and Corporal Arnold returned to the command post.

[101] At approximately 10:38 a.m., through the use of a spotting scope, Constable Shaw confirmed that Mr. George was in the residence. There was no indication that anyone was at the property other than Mr. George and his four dogs. Constable Shaw was able to observe Mr. George without being seen. He continued to make observations of Mr. George for approximately two-and-a-half hours, relaying them to the command post and to his team members by radio. During that time, he observed Mr. George enter and exit his home a number of times, generally carrying a rifle. He observed Mr. George walk in circles in the yard or go to one of the vehicles parked in the yard, typically the white Pontiac Montana van. To Constable Shaw, his actions were "very erratic and unpredictable."

[102] As per the operational plan, an attempt was also made by Constable Warwick, with his police service dog, and Constable Atkinson to move into place near the residence. However, they discovered that the area was covered by thick brush and underbrush and had approximately 1.5 kilometres still to travel to get to the residence when Mr. George was first sighted by Constable Shaw having entered his vehicle with a rifle. Consequently, the members were instructed to reposition themselves at Mr. George's driveway so that they would be in a position to assist if a confrontation occurred.

[103] Constable Shaw observed Mr. George driving erratically about the property, up and down the driveway at high speeds with music blaring. On numerous occasions, Mr. George reportedly took short drives about the property in this manner, returned to the residence and locked the vehicle, entered the residence, came outside and completed a similar routine a minute later. Constable Shaw's communications to his team members over the radio reporting such actions by Mr. George were recorded and formed part of the investigation record.

[104] At one point, Mr. George exited his residence with the rifle and began pointing it at different spots of the bush line, then put it back down. He repeated that action a number of times, and pointed the rifle in Constable Shaw's direction at one point, although Constable Shaw indicated that he was confident that he could not be seen by Mr. George.

[105] At another point, Mr. George walked up the driveway with the rifle in his hands and with his four dogs. As he walked past, and within 25 metres from, Constable Shaw, Constable Shaw observed Mr. George load his rifle. Mr. George left Constable Shaw's sight and shortly thereafter Constable Shaw could clearly hear other members yelling "Polizie, Halt." Minutes later, Mr. George returned to the residence on foot with his dogs and the rifle in his hands.

[106] Approximately two hours into his observations, Constable Shaw saw Mr. George park his vehicle in front of the residence and go inside the house and remove his jacket. Mr. George walked about his residence, gesturing with his hands and speaking as though he was having a heated conversation with someone. However, no one else appeared to be present with Mr. George. Mr. George subsequently exited the residence and added what appeared to be gasoline to the fuel tank of his white van. Mr. George did not have the rifle in his hands at this point, but he was only approximately 12 metres from the front deck of the residence, which was the last location that Constable Shaw had seen him with the rifle.

[107] According to Constable Shaw, this information was relayed to Corporal Brown, and they discussed whether or not Constable Shaw should possibly rush him because both of Mr. George's hands were occupied with the gas can. The problem was that Constable Shaw was there on his own and assistance was too far away. He was also concerned that the dogs would give him away if he got any closer. It was possible that if that happened, Mr. George would have time to get his firearm.

[108] Mr. George was subsequently observed returning to the residence and then exiting with the rifle. He attempted to start an ATV but abandoned, it as it stalled after a short distance. Mr. George reportedly returned to the white van and accelerated up the driveway at a high rate of speed, which Constable Shaw estimated to be 70 to 80 kilometres per hour, and out of Constable Shaw's view. Moments later, Constable Shaw reported that he heard what sounded like gunshots. Constable Shaw remained in his position until other members of the team made their way to the residence on foot.

Finding: Constable Shaw stalked to a position near the George residence and reported his observations over the radio in a continual and detailed manner.

Actions of the NDERT Crisis Negotiation Team

[109] RCMP policy states that deployment of a Crisis Negotiation Team (CNT) must be considered for an ERT deployment.Footnote 21 In this case, a decision was made to deploy such a team with the NDERT. The objective of a CNT in such an incident is to negotiate the safe surrender of a subject without death or injury to anyone.Footnote 22 Negotiation tactics and strategies are approved by the Incident Commander.Footnote 23 The team consisted of Corporal Stevenson as the primary negotiator and Corporal Garcia as the secondary negotiator.

[110] According to RCMP policy, a full team consists of four positions: a team leader, a primary negotiator, a secondary negotiator, and a scribe. Policy also provides that under exigent circumstances a negotiator may commence negotiation without a complete team. Considerations include the availability of crisis negotiators, response time, anticipated length of incident and type of incident. In its response to the Commission's complaint, the RCMP stated that at the time it was a common practice within the North District to have only two negotiators respond to most calls and arrange for additional resources where required. That practice was attributed to the remoteness and availability of sufficient negotiators to cover what is an extensive area. Corporal Garcia stated to investigators that they cannot always find four negotiators, but they never go with less than two.

[111] In response to a recommendation made by the IOR, the RCMP stated that every effort should be made by the Incident Commander to have a complete team and that the full team should respond unless there are exigent circumstances. The RCMP noted that the North District's current practice is to deploy three negotiators when feasible and practical, and a fourth if necessary. In the Commission's view, that practice is in line with the policy and the considerations set out within that policy for having less than a complete team.