Commission's Final Report after Commissioner's Response Regarding the Death of Mr. Victor Duarte in a Motor Vehicle Incident in Langley, British Columbia

PDF Format [470KB]

Related Links

- News Release

January 10, 2013 - Chair-Initiated Complaint

January 10, 2013 - Interim Report

April 14, 2016 - Commissioner's Response

November 30, 2017

Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act

Subsection 45.72(2)

Complainant

Chairperson of the Civilian Review and

Complaints Commission

File No.: PC-2013-0073

Introduction

[1] On October 29, 2012, members of the Langley, British Columbia, RCMP Traffic Section were conducting a targeted traffic enforcement operation along 0 Avenue in Langley in response to complaints from the public of speeding and aggressive driving in the area. The RCMP members involved were also using an Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) system to monitor passing traffic. Members attempted to stop a truck identified by the ALPR system as being associated to a prohibited driver. The truck failed to stop and fled on 240th Street.

[2] Two unmarked RCMP vehicles attempted to catch up to the fleeing truck but discontinued their attempts shortly thereafter. Within moments, the fleeing truck failed to stop at a stop sign at the intersection of 240th Street and 16th Avenue and collided with a semi-trailer truck. This collision caused the trailer to collide with a third vehicle driven by Victor Duarte. Mr. Duarte sustained fatal injuries as a result of the collision and died at the scene.

[3] The driver of the fleeing truck, Devon Laslop, sustained serious injuries in the collision but survived. Mr. Laslop was charged and convicted of flight from police causing death and was sentenced to three years in jail.

[4] On January 9, 2013, the then Interim Chairperson of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (now the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, hereinafter "the Commission")Footnote 1 initiated a complaint into this incident, to determine:

- whether the RCMP members or other persons appointed or employed under the authority of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act ("the RCMP Act") involved in the events of October 29, 2012, from the moment of initial identification of the suspect vehicle to the time of the collision, complied with all appropriate training, policies, procedures, guidelines and statutory requirements relating to speed enforcement and police vehicle pursuits; and,

- whether the RCMP's national-, divisional- and detachment-level policies, procedures and guidelines relating to speed enforcement and police vehicle pursuits are adequate.

[5] As provided by the RCMP Act, the complaint was investigated by the RCMP, who provided the Commission with a report authored by Superintendent D. R. Cooke dated June 30, 2014. In summary, the RCMP found minor deficiencies in the manner in which the RCMP members involved operated the traffic checkpoint and also found deficiencies in the RCMP pursuit policy. The report recommended minor changes to the wording of the RCMP national pursuit policy.

[6] The role of the Commission in matters such as these is remedial. That is to say, its purpose is not disciplinary but rather it strives to provide meaningful recommendations that improve the quality of policing and accountability within the RCMP. To achieve this goal, the Commission is required to review the RCMP's handling of the public complaint and to prepare a written report setting out its findings and recommendations. This written report consists of three parts. First, the Commission issues an Interim Report following its initial review of the RCMP's report. Second, the RCMP Commissioner responds to the Commission's Interim Report. And finally, the Commission considers the RCMP Commissioner's response and issues a Final Report.

[7] The Commission issued its Interim Report on April 14, 2016. On December 7, 2017, the Commission received a response from the RCMP Commissioner's delegate, Assistant Commissioner Stephen White. This report is the Commission's Final Report into the matter and concludes the review process.

The Commission's Review

[8] The Commission is an agency of the federal government, distinct and independent from the RCMP. When reviewing RCMP reports, the Commission acts independently and reaches its conclusions after an objective examination of all the evidence.

[9] The circumstances of the incident were also examined by the Independent Investigations Office of British Columbia (IIO). The mandate of the IIO is to examine the conduct of the RCMP members involved and to determine whether an offence may have been committed. On December 20, 2012, the IIO submitted its report and concluded that no criminal offences were committed by the RCMP members involved.

[10] The findings and recommendations made by this Commission are distinct from those of the IIO in that the Commission's findings and recommendations are not criminal in nature, nor are they intended to convey any aspect of criminal culpability. Although some terms used in this report may concurrently be used in the criminal context, such language is not intended to include any of the requirements of the criminal law with respect to guilt, innocence, or the standard of proof.

[11] The Commission's findings are based on a thorough review of the RCMP's operational file, including: statements, notes, expert reports, photographs, audio recordings, and video evidence; the RCMP's investigation into the Commission's complaint; the RCMP's report to the Commission; and the report of the IIO. The Commission has also thoroughly canvassed RCMP policy at the national, divisional and detachment level as well as prevailing law and academic research on the topic of police pursuits.

Background Facts

[12] The following account of events flows from witness statements provided during the police investigation, audio logs of conversations between RCMP members and RCMP dispatch, as well as in-car video camera footage and GPS tracking information retrieved from the RCMP vehicles involved. The Commission puts these facts forward, as they are either undisputed or because, on the preponderance of evidence, the Commission accepts them as a reliable version of what transpired.

[13] The Commission notes that the availability of in-car video footage from several police vehicles involved provided multiple vantage points of the entire incident and was invaluable in arriving at an objective conclusion as to the sequence of events. The benefit of in-car video recordings to an independent investigation cannot be overstated and is encouraged as a best practice.

[14] The Langley RCMP had received complaints of speeding vehicles and aggressive driving in the area of 0 Avenue in Langley. In response to these complaints, in the late afternoon of October 29, 2012, Langley RCMP Traffic supervisor Corporal Patrick Davies along with Constables Derek Cheng, Gaenor Cox, Robert Johnston, and Hayden Willems were conducting targeted traffic enforcement at the intersection of 0 Avenue and 240th Street.

[15] The RCMP members were targeting vehicles travelling on 0 Avenue. When a violator was identified, Corporal Davies and Constable Cheng, who were on foot, would direct the violator to turn onto 240th Street, where the remaining members would take the applicable enforcement action.

[16] In addition to targeting speeding vehicles, Constable Cox was operating an ALPR system. The ALPR system automatically recognizes licence plates on passing vehicles and rapidly conducts computer checks for violations such as stolen vehicles or licence plates and suspended or prohibited drivers. Members are notified only when the computer detects a "hit" on an approaching vehicle.

[17] At 5:26 p.m., the ALPR system notified Constable Cox that an approaching pickup truck was associated to a driver subject to a provincial licence suspension. Constable Cox relayed this information to the other members via police radio.

[18] Using hand signals, Corporal Davies and Constable Cheng directed the pickup truck to turn down 240th Street. The driver of the truck complied by turning down 240th Street, but did not stop. Instead, he continued driving on 240th Street and increased speed.

[19] Constable Johnston was beside his police vehicle on 240th Street. His police vehicle was an unmarked SUV pointed towards 0 Avenue. He observed the truck's failure to stop and immediately entered his police vehicle with the intention of stopping the truck.

[20] Constable Johnston took 18 seconds to get into his vehicle and to perform a three-point turn to get oriented in the right direction. During this manoeuvre, he activated the emergency lights and siren on his police vehicle.

[21] Constable Johnston then began to accelerate to catch up to the pickup truck.

[22] The in-car video recordings reveal that the pickup truck was within sight of Constable Johnston's police vehicle for only the first 8 seconds of flight. It is evident that the pickup truck was travelling at high speed, and in any event, faster than Constable Johnston.

[23] Forty-nine seconds later, Constable Johnston turned off his emergency equipment and came to a complete stop on the side of the road and indicated via police radio that the pickup truck was attempting to flee and that he was discontinuing his pursuit.

[24] Meanwhile, Constable Cheng had begun to follow Constable Johnston. Constable Cheng was also driving an unmarked police vehicle and was approximately 14 seconds behind Constable Johnston. Constable Cheng was also operating emergency lights and siren on his police vehicle.

[25] As soon as Constable Johnston told dispatch that he had discontinued his pursuit of the truck, Constable Cheng turned off his emergency equipment and slowed to a normal rate of speed. He passed by Constable Johnston's parked police vehicle and continued driving down 240th Street.

[26] One minute and fifteen seconds later, Constable Cheng reached the intersection of 240th Street and 16th Avenue and observed that a collision had occurred. Sufficient time had elapsed between the collision and Constable Cheng's arrival that several other motorists had exited their vehicles and begun to provide first aid assistance to the injured parties.

[27] Mr. Laslop, the driver of the fleeing pickup truck, can be seen on the in-car video recordings to be lying in middle of the roadway, apparently ejected from his truck. Mr. Duarte, meanwhile, was trapped in his vehicle. No other parties were injured in the collision.

[28] Constable Cheng immediately radioed for additional assistance. Other RCMP members as well as fire and emergency medical personnel were dispatched to the scene. Constable Cheng began to provide first aid assistance and relayed information to dispatch regarding the severity of injuries.

[29] Mr. Duarte was ultimately declared deceased at the scene. Mr. Laslop was transported to hospital via air ambulance, escorted by an RCMP member.

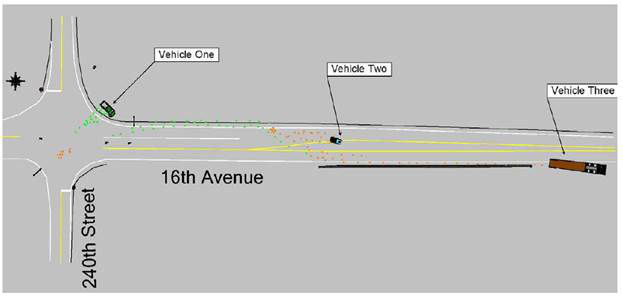

[30] The RCMP Integrated Collision Analysis and Reconstruction Service (ICARS) completed a comprehensive investigation of the collision scene. The diagram below was prepared by ICARS and depicts the scene as found after the collision. Vehicle One identified in the diagram is the pickup truck driven by Mr. Laslop. Vehicle Two is the car driven by Mr. Duarte. Vehicle Three is the semi-trailer involved.

[31] The ICARS report concluded that Mr. Laslop's pickup truck was travelling northbound on 240th Street and collided with the right side of the trailer of the semi-trailer truck, which was travelling eastbound on 16th Avenue. After this impact, Mr. Laslop's pickup truck rotated 135 degrees clockwise and left the roadway just north-east of the intersection.

[32] Meanwhile, the trailer of the semi-trailer truck was pushed into the westbound lane of 16th Avenue. Mr. Duarte's vehicle was travelling westbound on 16th Avenue and collided with the left side of the trailer.

[33] The RCMP also retained an outside expert forensic engineering firm to investigate the collision. This firm prepared a report certified by a professional engineer in which Mr. Laslop's pickup truck was determined to be travelling at a speed of 150km/h approximately five seconds before the collision. The posted speed limit on 240th Street is 60 km/h.

[34] The RCMP's criminal investigation into Mr. Laslop confirmed that at the time of the incident, Mr. Laslop was a prohibited driver in British Columbia. This prohibition stemmed from the provisions of the British Columbia Motor Vehicle Act and was the result of a lengthy driving record which included 31 provincial traffic violations between 2004 and 2012. These violations included two prior convictions for driving while prohibited.

[35] The RCMP recommended charges and the Crown ultimately charged Mr. Laslop with three offences: flight from police causing death (section 249.1 Criminal Code), dangerous driving causing death (subsection 249(4) Criminal Code), and driving while prohibited (section 95 British Columbia Motor Vehicle Act).

[36] Mr. Laslop pled guilty and was convicted of flight from police causing death and driving while prohibited, resulting in a three-year jail sentence as well as fines and additional driving prohibitions.

The Commission's Findings and Recommendations

[37] The Commission's Interim Report arrived at six interim findings and eleven interim recommendations concerning the incident. Assistant Commissioner White agreed with four of the Commission's interim findings and supported six of the Commission's interim recommendations.

[38] The Commission has considered the information contained in the response by Assistant Commissioner White and has set out its final findings and recommendations below. Where Assistant Commissioner White did not agree with the Commission's interim findings or recommendations, additional analysis is contained in this report to reach the Commission's final conclusions.

Interim Finding No. 1: The RCMP members involved in the events of October 29, 2012, failed to comply with "E" Division Operational Manual policy, which required members to ensure that safety precautions were taken.

Interim Finding No. 2: Corporal Davies failed to properly supervise the traffic checkpoint operation.

[39] At the national level, RCMP policy provided limited guidance on the operation of traffic enforcement checkpoints. Relevant policy was found within part 5 of the RCMP national Operational Manual, and included the following:

1.2. Traffic enforcement and safety programs should be selectively planned by analyzing collision statistics, seat belt and impaired driving, with enforcement/compliance, surveys, traffic volume, and weather.

1.3. Members performing traffic duties must identify road safety issues in their area. Identified road safety issues should be aggressively enforced.

. . .

2.1. While outside a police vehicle, a member performing traffic duties must at all times wear an approved high-visibility vest or jacket.

. . .

3.1. The courts have ruled the detention of motorists in a traffic checkpoint is an arbitrary detention which infringes upon sec. 9, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, the courts have held decisions that traffic checkpoints are justified pursuant to sec. 1 of the Charter to combat grave and pressing problems arising from death and injury caused by the dangerous operation of vehicles. Traffic checkpoints are to be used only to enforce traffic-related laws.3.2. The courts have ruled it is appropriate for police conducting traffic checkpoints to ask questions concerning the mechanical condition of the vehicle, and require the driver to produce his/her driver's licence, vehicle registration and insurance coverage.Footnote 2

[40] The RCMP divisional Operational Manual provides a similar degree of guidance for operations in British Columbia. The relevant portions include the following:

1.1 Enforcement of traffic laws and delivery of traffic safety programs must be a planned activity, predicated on an analysis of collisions and other traffic problems.

. . .

3.2.1. When conducting any type of traffic enforcement or performing traffic control duty, ensure that safety precautions are taken, for the protection of the public, and police personnel.[Emphasis added]Footnote 3

[41] In the present case, at least one RCMP member on scene was aware that the setup of the enforcement checkpoint was potentially confusing for motorists. In his statement to the IIO, Constable Johnston stated:

On numerous occasions, vehicles have been directed by RCMP members to pull off onto these Streets from 0 Avenue, sometimes the vehicles continue north bound on the Streets. The members then proceed to close the distance on the vehicles stopping them 4 to 6 blocks north of 0 Avenue. The most common reason from drivers is that they believed the member was directing them north due to the road being closed due to a detour or closure. [sic throughout]

[42] Mr. Laslop provided a statement to the IIO. In this statement, Mr. Laslop stated that when he was initially directed to turn from 0 Avenue onto 240th Street, he believed it was due to a detour, thus adding credence to Constable Johnston's comments.

[43] Despite this knowledge, the traffic operation was not set up in a manner to ease the confusion. Three of the four police vehicles in use were unmarked vehicles and all four vehicles were parked on the same side of 240th Street and all were facing 0 Avenue. The vehicles did not have emergency lights activated that would be visible to traffic being directed to turn onto 240th Street from 0 Avenue, nor was there a member present to issue clear directions to vehicle drivers.

[44] The statement provided by Constable Johnston suggests that members relied on turning around and closing the distance instead of proactively taking steps to ensure that drivers were given clear instructions.

[45] The action of "closing the distance" is described in RCMP policy. This policy reads in part as follows:

8.1. Attempting to close the distance (catching up) between a police vehicle and another vehicle is not the same as a pursuit.

8.2. Before attempting to close the distance, a risk assessment must be applied and public/police safety considered. The risk assessment process will be continually applied.

8.3. Emergency lights must be used when closing the distance. The siren will also be used if the risk assessment indicates a risk to public and police safety. The siren may be discontinued once the offender's vehicle has pulled over and stopped for the police vehicle.Footnote 4

[46] The fact that the RCMP policy highlights the need for a continuous risk assessment implies that the act of closing the distance is inherently dangerous. Closing the distance will necessarily mean that the police vehicle travels faster than the target vehicle. If a target vehicle is driving at or near the speed limit, this means that the police vehicle must significantly exceed the speed limit to catch up.

[47] This implication is bolstered by the British Columbia Emergency Vehicle Driving RegulationsFootnote 5 enacted pursuant to the Motor Vehicle Act,which define closing the distance as increasing the risk of harm. The regulations include the following:

4 (6) Factors which will increase the risk of harm to members of the public for purposes of subsections (1), (2) and (5) include attempting to close the distance between a peace officer's vehicle and another vehicle . . . .

[48] Based on these factors, the Commission finds that the process of "closing the distance" is inherently dangerous.

[49] In the present case, the GPS tracking data suggests that in closing the distance, the police vehicles involved reached a speed of approximately 120km/h in a posted 60km/h zone.

[50] Knowing that drivers were confused by the traffic operation, it was incumbent on the RCMP members present to take appropriate safety precautions to reduce the risk to the public. In the present case, this would have included eliminating the confusion and ensuring that drivers received clear instructions. In failing to do so, the members present violated the RCMP divisional policy.

[51] As the ranking member present, a greater onus was on Corporal Davies to ensure that the checkpoint operation was set up in a safe manner.

[52] Assistant Commissioner White agreed with both of these interim findings. Accordingly, they are incorporated unchanged into the Commission's Final Report.

Interim Finding No. 3: Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng engaged in a pursuit contrary to policy.

Interim Finding No. 4: Corporal Davies failed to direct Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng to discontinue their pursuit.

[53] Assistant Commissioner White did not agree with these two findings, as he did not agree that the policy definition of a "pursuit" was met in the facts of this case.

[54] Assistant Commissioner White included a variety of reasons to support his opinion. In the Commission's view, it is unnecessary to address each of these points individually for the reasons that follow.

[55] The RCMP's vehicle pursuit policy requires a two-step analysis. To be defined as a pursuit, a driver would need to:

- Refuse to stop as directed by a peace officer; and

- Attempt to evade apprehension.Footnote 6

[56] Assistant Commissioner White adopted a strict reading of this policy in arriving at his opinion that the involved members had not initiated a pursuit. Specifically, he relied upon the fact that Mr. Laslop had not been clearly directed to stop after turning onto 240th Street to support the contention that Constables Johnston and Cheng had not engaged in a pursuit when they attempted to close the distance with him. In short, absent a clear unambiguous direction to stop, the pursuit definition has not been met.

[57] In contrast, the Commission adopts a purposive approach to this question. In the Commission's view, while there may not have been a clear unambiguous direction for Mr. Laslop to stop initially, the overall circumstances would lead a reasonable police officer to conclude that Mr. Laslop was fleeing and that therefore, the pursuit policy ought to apply.

[58] Unlike statute law, policies are designed as guidelines. That is to say, they are designed to provide guidance to employees on how to approach a given situation. Generally speaking, policies do not conceive of every possibility and for that reason, deviations from policy are often appropriate, with appropriate justification. With that in mind, it is clear that understanding the purpose of a policy can often be as important as its precise wording.

[59] The RCMP has not provided the Commission with any background information on the underlying purpose behind the RCMP's pursuit policy. However, from the extensive body of research materials reviewed by the Commission in this matter and from the regular and repeated interest by the public and the media in tragic cases involving police pursuits, it is reasonable to conclude that at least one purpose underlying the RCMP's policy on pursuits is to reduce the risk of injuries and fatalities by limiting vehicle pursuits where possible.

[60] That is to say, the risks involved in attempting to apprehend a driver are sometimes too high and public safety must prevail.

[61] Through such a lens, the Commission finds that the members at the checkpoint knew that Mr. Laslop was attempting to flee. Whether or not the RCMP's pursuit definition was strictly met, Mr. Laslop was acting in a manner consistent with a driver attempting to evade the police. The Commission's conclusion is based on the following facts:

- Constable Johnston stated that "[he] observed Cst. CHENG and Cpl. DAVIES start to run towards Cst. JOHNSTON's police cruiser, upon realizing the vehicle was not going to stop. . . ."

- Constable Cheng stated that he "yelled at Cst. JOHNSTON words to the effect of, "Bobby! Stop that truck taking off on us! He's a prohib[ited] driver!"

- Two police vehicles immediately began to intercept Mr. Laslop's vehicle. Were this a case where the members merely needed to signal a confused driver to pull over (as had been suggested by some of the involved members), it is unlikely that two police vehicles would have been required. It is more likely that the members recognized that Mr. Laslop was attempting to flee.

- Mr. Laslop accelerated quickly away from the police checkpoint. Constable Johnston estimated that Mr. Laslop was driving twice the posted speed limit as he drove away. This is not consistent with a driver who was confused and had just passed by several police officers.

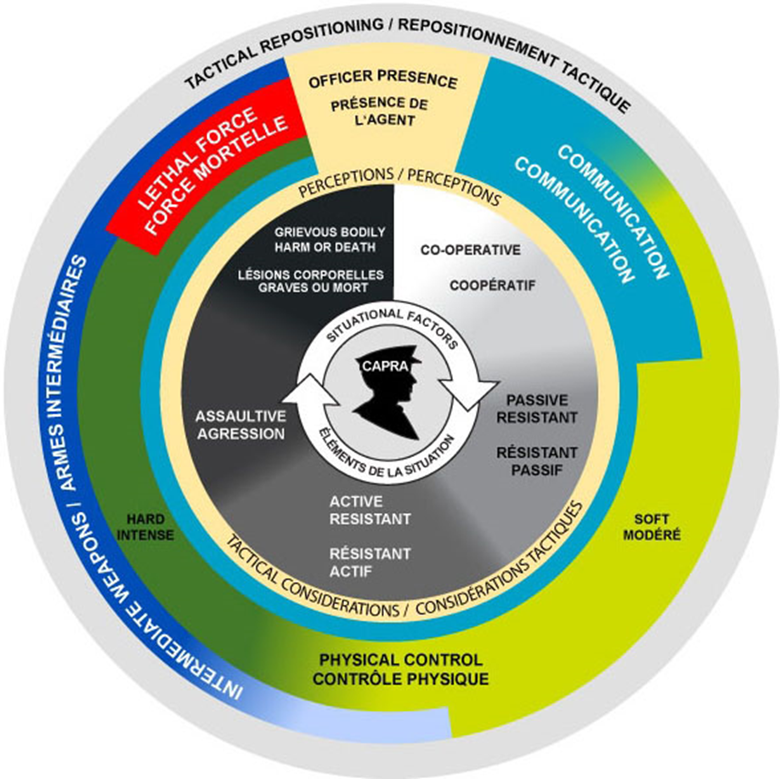

- Corporal Davies stated that "[t]he pickup completed its turn, and then instead of pulling over, accelerated north on 240 Street. . . . Cpl. DAVIES got on the police radio main channel, and informed dispatch that a vehicle had failed to stop for officers at the stationary road check. . . . Cpl. DAVIES requested that Chilliwack R.C.M.P. be informed, so that an officer could attend [Mr. Laslop's] address. Cpl. DAVIES inquired whether Air One (the police helicopter) was available, but it was not. The vehicle description was broadcast to other R.C.M.P. officers in the Aldergrove area."

[62] Based on these factors, the Commission finds that it ought to have been evident to a reasonable police officer that Mr. Laslop's driving conduct was consistent with a driver who was attempting to flee. In such a circumstance, it would have been reasonable to have applied the RCMP's pursuit policy to decide whether or not to chase Mr. Laslop.

[63] Having said that, the Commission recognizes that two agencies—the RCMP and the Commission—have arrived at different results in this analysis. Moreover, it is also important to recall that the involved members had mere seconds to decide on a response. Years later, debate continues on whether the RCMP's pursuit policy ought to apply. Finally, the two pursuing members did recognize that Mr. Laslop was fleeing within moments of beginning their pursuit and then properly applied the existing policy to terminate the pursuit.

[64] For these reasons, the Commission's Interim Report did not include any remedial recommendations aimed at the involved members. To the Commission, the main issue involved is a failure of the RCMP's policy, not a failure of its members. The RCMP's vehicle pursuit policy is not sufficiently clear and fails to provide sufficient guidance to its members in situations such as this one.

[65] Accordingly, although the Commission maintains its position that Constables Johnston and Cheng engaged in a pursuit contrary to policy, the findings have been reworded to clearly express the source of the problem as follows:

Finding No. 3 Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng engaged in a pursuit contrary to policy due to ambiguity in the RCMP's pursuit policy.

Finding No. 4: Corporal Davies failed to direct Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng to discontinue their pursuit due to ambiguity in the RCMP's pursuit policy.

Interim Finding No. 5: The RCMP national policies relating to traffic checkpoints are inadequate.

[66] Neither national nor divisional RCMP policy offers clear guidance on the operation of traffic checkpoints. The Commission appreciates that the wide scope of RCMP duties and responsibilities involving policing in both urban and rural areas necessarily means that policy must allow some degree of discretion. However, the Commission finds that a policy statement that members must "ensure that safety precautions are taken, for the protection of the public, and police personnel,"Footnote 7 without any description or training related to what such appropriate safety precautions may be is, at best, unhelpful. At worst, this policy transfers liability to members to ensure safety without providing guidance or training to them on how to accomplish this goal.

[67] Assistant Commissioner White agreed with this finding. Accordingly, it is included unchanged in the Commission's Final Report.

Interim Finding No. 6: The RCMP national policies relating to police vehicle pursuits are inadequate.

[68] Police vehicle pursuits have long been recognized to be a high-risk activity. For instance, in Parliamentary hearings related to amendments that ultimately made flight from police an offence under the Criminal Code, a witness testifying in front of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights stated that, in the province of Ontario alone, "between 1991 and 1997 over 10,000 high-speed chases occurred, which resulted in 2,415 people injured and 33 deaths."Footnote 8

[69] A 2003 report by the Queensland, Australia, Crime and Misconduct Commission on the topic of police pursuits noted that in Queensland, 29% of all pursuits studied involved a collision and 11% resulted in injury. The report noted that the driver was charged with a more serious offence than the one for which the police were pursuing them in less than 10% of cases.Footnote 9

[70] Meanwhile, the Justice Institute of British Columbia has estimated that up to 38% of police pursuits in British Columbia end in collisions with injuries in 15% of cases.Footnote 10

[71] Additionally, recent research from the United States suggests that approximately 30% of police pursuits end in vehicle collisions.Footnote 11 The researchers arrived at the conclusion that:

When a suspect refuses to stop, a routine encounter can turn quickly into a high-risk and dangerous pursuit where the officer's "show of authority" may affect the suspect's driving. As proactive enforcement may influence (i.e., increase) the number of suspects fleeing, there is a need for enhanced training for officers so they understand how their behavior affects the behavior of the fleeing suspect. . . .

Pursuing a suspect raises risks to all involved parties and innocent bystanders who happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. One way to help officers understand how to balance the risk and benefits of pursuit is to have them apply the same standards used in weighing the firing of a weapon in a situation where they may endanger innocent bystanders by shooting. . . . By comparison, in pursuit, the officer has not only his or her vehicle to worry about, but also must consider the path taken by the pursued vehicle and the driver's capacity and skill to control it. Indeed, the risk is amplified by dangerous situations created by innocent drivers attempting to get out of harm's ways.Footnote 12

[72] As a whole, the data suggest that there is a substantial risk of collision, injury, and death associated with police pursuits and that the discovery of a more serious underlying offence is relatively rare.

[73] Furthermore, the need for broad changes to the manner in which police pursuits are conducted has been echoed by researchers and police forces. Some excerpts from relevant reports include:

- The pursuits and emergency responses that generate the most risk to officers should be eliminated except in the most extreme situations. By way of another example, the number of pursuits, crashes, and deaths could be reduced if officers chased only violent felons. . . . Also, in the case of emergency responses, officers should recognize that few are necessary to protect life and the ones that are should be undertaken at slower speeds and without endangering themselves or others at intersections and other high-risk areas.Footnote 13

- All police drivers, managers and post-incident investigators must recognize that pursuits are inherently dangerous and that, when a pursuit is initiated, there is an unknown and unpredictable possibility that it will result in a collision. Once initiated, the officers have relatively little control over that risk in the majority of cases.Footnote 14

- . . . a categorical approach would provide the much needed mechanism to improve this area of the law. By recognizing high-speed pursuit as a valid exercise of police authority only for certain categories of suspects, this approach would prevent police officers from having to perform a complex balancing test in the seconds before a decision to pursue, [and] reduce the exposure of innocent third parties to the risk of injury from high-speed pursuits . . .

If the categorical mechanism were in place, it would provide a strong presumption against initiating a high-speed pursuit and rely instead on the possibility of later apprehension. A categorical approach would also create strong incentives to develop alternative methods of capturing suspects.Footnote 15

[74] Assistant Commissioner White generally agreed with this finding but disagreed in part with the associated recommendations. This will be explored in more detail in the recommendation portion of this report.

Interim Recommendation No. 1: That RCMP national policy be amended to provide specific guidance on the set-up of police checkpoints to minimize the risk of vehicle pursuits, including the use of an escape prevention vehicle and the use of fully marked police vehicles when available.

[76] In reviewing this matter, the Commission has studied academic research and police policies from various police forces in North America.

[77] The Commission has also considered the comments of Superintendent Cooke in his report on this matter. In this report, Superintendent Cooke notes at page 24 that:

I believe Cpl. Davies and Cst. Cheng should have made it very clear to the driver of the pick-up truck that he was to pull to the side of 240th Street and stop. This could have been accomplished through more specific hand gestures, by having a member on 240 Street in position to direct the pick-up truck to the side of the road, or by stopping the pick-up truck on 0 Avenue and speaking with the driver to provide specific direction.

[77] Superintendent Cooke formed this opinion after concluding on page 23 that:

. . . it is possible that the driver of the pick-up (or any other driver provided similar directions) could have believed there had been a collision or some other incident on 0 Avenue and he was simply being detoured. Such a belief would have been supported by the fact that no one specifically directed him to stop.

[78] Superintendent Cooke's opinion was supported by the interview with Constable Johnston, who told the IIO investigator that it was not uncommon for drivers at this particular location to not immediately stop until members pulled them over with a police vehicle, and by the statement given by Mr. Laslop to the IIO in which he states that he was initially confused by the direction given by the members.

[79] The research studied by the Commission suggests that one aspect of an individual's decision to flee from police is based upon their assessment of the likelihood of a successful escape. That is to say, the more likely it is that an individual perceives that they will successfully escape police, the more likely it is that they will attempt to flee.Footnote 16

[80] In the present case, the set-up of the traffic enforcement operation resulted in the following factors when attempting to stop Mr. Laslop:

- Ambiguous hand gestures to Mr. Laslop that did not clearly direct him to stop;

- No barriers or impediments on 240th Street that would interfere with Mr. Laslop's ability to flee;

- All visible police vehicles parked in the wrong direction (i.e. towards 0 Avenue) to pursue Mr. Laslop;

- A long, empty and straight stretch of roadway for Mr. Laslop to quickly accelerate.

[81] A more structured operation may have reduced the likelihood of Mr. Laslop's attempt to flee. Based on a review of academic literature and the specific circumstances of this review, the Commission has drafted the following general steps that should be considered when implementing police checkpoints, for the RCMP's consideration when drafting policy or training with respect to checkpoints:

- Selection of a roadway where the posted speed limit, visibility, and traffic volume permit drivers sufficient time to slow and stop upon direction by police;

- Positioning of police vehicles and traffic cones in a manner that requires vehicles to slow and manoeuvre, thus permitting members to issue a direction to stop and allowing members time to view and identify the driver;

- Positioning police vehicles in a manner and orientation that they are ready to immediately stop a vehicle if necessary;

- The use of a portable or hand-held "STOP" sign to ensure that the requirement to stop is made clear;

- Positioning of an "escape prevention vehicle" equipped with a tire deflation device parked sufficiently close so as to remain visible to drivers at the checkpoint but far enough away to allow a tire deflation device to be deployed if necessary.

[82] The "escape prevention vehicle" equipped with a tire deflation device serves three purposes. First, it provides a visible deterrence to drivers who may be tempted to flee; knowing that a vehicle is positioned ahead and ready to intercept reduces the perception of a successful escape. Second, it allows the deployment of a tire deflation device if a vehicle fails to stop. Such a deployment does not necessarily invoke the pursuit policy or require a pursuit. Finally, the vehicle provides advance warning to drivers travelling in the opposite direction (i.e. towards the checkpoint on 240th Street) and thus reduces the risk of injury due to traffic collisions at the checkpoint.

[83] The use of unmarked vehicles should be discouraged at a traffic checkpoint. The RCMP divisional policy states that:

4.1.1.2 The percentage of "clean-roof" and fully unmarked vehicles must not exceed 40% (20% for each type) of the total vehicles on strength to the traffic services unit.Footnote 17

[84] In the present incident, of the total vehicles involved in the traffic operation, only one (20%) was a fully marked vehicle. While this is not necessarily indicative of the total vehicles on strength to the traffic services unitFootnote 18 and therefore not necessarily in breach of the policy, the lack of fully marked vehicles may have contributed to the confusion noted by Constable Johnston.

[85] This view finds some support in RCMP national policy. The RCMP Incident Management/Intervention Model (IM/IM) policy notes the following with respect to officer presence:

While not strictly an intervention option, the simple presence of an officer can affect both the subject and the situation. Visible signs of authority such as uniforms and marked police cars can change a subject's behaviour.[Emphasis added]Footnote 19

[86] The Commission recommends that as a part of national policy, fully marked vehicles should be used when available for traffic checkpoints.

[87] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Accordingly, it is included in the Commission's Final Report without additional comment.

Interim Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP provide additional training to any regular member involved in checkpoint operations on how to plan vehicle checkpoints so as to minimize the risk of pursuits and vehicle collisions. This training should also emphasize alternative methods of enforcement.

[88] In ad dition to policy changes, traffic operations are a high-risk area and ought to be the subject of operational training. In his report to the Commission, Superintendent Cooke describes the training provided to the members involved. The training with respect to vehicle checkpoints appears limited to instruction on the use of hand gestures during RCMP basic training. No refresher training or training in relation to the planning of checkpoints appears to have been conducted.

[89] It is essential that any member involved in planning a checkpoint be given training on how to minimize the risks inherent in such an operation. In addition to the risks of a pursuit, traffic checkpoints are a high risk to members on foot in terms of being struck by a vehicle and to the public, whose reaction to a traffic checkpoint may increase the risk of collisions between vehicles.

[90] Furthermore, this training should highlight alternative methods of enforcement such as issuing violation tickets or a summons at a later date should a vehicle evade the checkpoint. The use of a video camera to record the identity of drivers and infractions could be of benefit to such a course of action.

[91] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Accordingly, it is included in the Commission's Final Report without additional comment.

Interim Recommendation No. 3: That RCMP national policy be amended to remove the concept of "closing the distance."

[92] The present incident is a particularly tragic example of how Mr. Laslop's perception that he was still being pursued by police led to his decision to enter a 4-way intersection at nearly 150 km/h to evade capture for a provincial traffic offence. This perception was arguably linked to the RCMP members' use of the "closing the distance" policy.

[93] The Commission agrees with Superintendent Cooke's conclusion in his report that the RCMP pursuit policy definitions of "closing the distance" and "pursuit" are unclear. This finding has also been echoed in academic research that noted that "closing the distance" is "functionally equivalent to pursuits."Footnote 20

[94] Instead of a permissive policy of "closing the distance" that may be broadly interpreted, the Commission recommends eliminating the concept of "closing the distance" in favour of a clearer definition of pursuit with an articulable threshold for when a pursuit begins.

[95] As per the prevailing research previously discussed, such a policy should be based on the actions of the driver of the subject (or target) vehicle and not the police vehicle, as the purpose of the policy is to reduce risk. If a subject vehicle is driven in a manner to evade police, the risk level necessarily increases, and therefore the pursuit policy should apply.

[96] Assistant Commissioner White did not agree with this recommendation. He contends that this concept is necessary to ensure that policy control is maintained over police driving that is intended to "catch up" to violators in routine traffic stops.

[97] The Commission agrees that the RCMP ought to ensure that policy is in place to govern "routine" emergency driving. The Commission's concern with the concept of "closing the distance" is that it lends itself to be conflated with an actual pursuit. Superintendent Cooke, who drafted the RCMP's report into this incident, inadvertently provided an example of how the concept of "closing the distance" can be erroneously applied to what should be classified as a police pursuit:

It was also reasonable for the officers to believe that if in the first instance the driver was attempting to take advantage of the manner in which he was directed onto 240 Street, that he may have stopped for police once a police car "closed the distance" and signalled him to pull over. I can state unequivocally from my own 32+ years of policing experience that I have encountered many instances in which drivers made an effort to avoid being pulled over by the police (by turning onto a side road or other means), but would not engage in a pursuit once the police had pulled in behind with a police vehicle and signaled him/her to stop.

[98] In this excerpt, Superintendent Cooke suggests that it is acceptable to "close the distance" and pull in behind a target vehicle despite efforts made by the driver to evade police. Superintendent Cooke's position is, with respect, not that reflected in the RCMP national policy. Under the existing policy, once a vehicle has refused to stop for police and has made an attempt to evade police, the pursuit policy—and not the "closing the distance" policy—must immediately apply.

[99] In the Commission's view, the concept of "closing the distance" in a routine traffic stop scenario must be clearly differentiated from the vehicle pursuit policy to avoid confusion. To address Assistant Commissioner White's concerns, the Commission has modified the language of this recommendation as follows:

Recommendation No. 3: That RCMP national policy be amended to remove the concept of "closing the distance" in the context of police pursuits. "Closing the distance" should refer only to police emergency driving involving routine violator apprehension where there is no indicia of a driver's attempt to flee.

Interim Recommendation No. 4: That the definition of a "pursuit" in RCMP national policy incorporate the concept that a pursuit begins once the driver of a subject vehicle takes any evasive action to distance the vehicle from police, regardless of whether police emergency equipment has been activated on the police vehicle(s) involved in attempting to intercept the subject vehicle.

[100] Assistant Commissioner White did not agree with this recommendation on the basis that it was redundant to the existing policy.

[101] The Commission disagrees with this assessment. The Commission's recommendation removes the troublesome requirement of the existing policy that requires that a driver refuse to stop as directed by a peace officer, in favour of an assessment of the fleeing driver's conduct. In short, if a driver behaves as though he is attempting to evade the police, policy should consider the situation a pursuit instead of parsing the issue of whether a clear attempt was made to signal the driver to stop.

[102] Consequently, the Commission reiterates this recommendation.

Interim Recommendation No. 5: That RCMP national policy impose a requirement on members to immediately discontinue attempts to stop a vehicle once the pursuit definition is met, unless the pursuit may continue pursuant to criteria outlined in the policy. (The criteria is proposed in Recommendation No. 8.)

[103] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Accordingly, it is included in the Commission's Final Report without additional comment.

Interim Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP Incident Management/Intervention Model be amended to include vehicle pursuits under the "lethal force" category.

[104] RCMP national policy appears to suggest a link between pursuits and use of force. The Emergency Vehicle Operations (Pursuits) policy notes as follows:

1.2 The Incident Management Intervention Model (IMIM) must guide any decision to initiate, continue, or terminate an emergency vehicle operation. See ch. 17.1.Footnote 21

[105] The IM/IM, which is used to train and guide members in the use of force, promotes risk assessment and depicts various levels of behaviours and reasonable intervention options. The IM/IM is based on the principle that the best strategy employs the least intervention necessary to manage risk. Accordingly, the best intervention causes the least harm or damage. The guide promotes the use of verbal interventions wherever possible, both to defuse potentially volatile situations and to promote professional, polite and respectful attitudes to all. These guidelines are based on situational factors when determining whether to use force and what amount of force is necessary in the circumstances.

[106] While the RCMP pursuit policy directs the reader to the IM/IM policy, the IM/IM policy does not include information related to driving or police pursuits. The IM/IM is summarized in a "wheel" that depicts subject behaviour and appropriate officer response based on the subject's behaviour:

Text Version

[107] The IM/IM policy includes risk assessment tools based on situational factors, subject behaviours, perception and tactical considerations, as well as intervention options. Despite it being referenced by the RCMP vehicle pursuit policy, the IM/IM policy does not address vehicle pursuits in any fashion.

[108] The levels of force that may be employed by the members are described in the IM/IM as follows:Footnote 22

Officer Presence

While not strictly an intervention option, the simple presence of an officer can affect both the subject and the situation. Visible signs of authority such as uniforms and marked police cars can change a subject's behaviour.

Communication

An officer can use verbal and non-verbal communication to control and/or resolve the situation.

Physical Control

The model identifies two levels of physical control: soft and hard. In general, physical control means any physical technique used to control the subject that does not involve the use of a weapon.

Soft techniques may be utilized to cause distraction in order to facilitate the application of a control technique. Distraction techniques include but are not limited to open hand strikes and pressure points. Control techniques include escorting and/or restraining techniques, joint locks and non-resistant handcuffing which have a lower probability of causing injury.

Hard techniques are intended to stop a subject's behaviour or to allow application of a control technique and have a higher probability of causing injury. They may include empty hand strikes such as punches and kicks. Vascular Neck Restraint (Carotid Control) is also a hard technique.

Intermediate Weapons

This intervention option involves the use of a less-lethal weapon. Less-lethal weapons are those whose primary use is not intended to cause serious injury or death. Kinetic energy weapons, aerosols and conducted energy weapons fall within this heading.

Lethal Force

This intervention option primarily involves the use of conventional police firearms (duty pistol, shotgun, rifle, patrol rifle etc). The use of these firearms are intended to, or are reasonably likely to cause serious bodily injury or death through ballistic force, i.e., a lead projectile, when facing subject behaviour(s) that may result in Grievous Bodily Harm or Death.

[109] The empirical evidence already discussed suggests that vehicle pursuits create a significant risk of grievous bodily harm or death.

[110] In the Commission's view, vehicle pursuits should be included in the IM/IM definition of "lethal force."

[111] Assistant Commissioner White did not support this recommendation. He explained the purpose of police vehicles and expressed his opinion concerning the use of police vehicles as weapons.

[112] There appears to be some confusion with respect to this recommendation. The Commission's recommendation was not that police vehicles be included in the IM/IM as a lethal force option. Instead, it was vehicle pursuits that were the subject of the recommendation. The Commission was not suggesting that police officers consider their police vehicle as a lethal weapon or that it be employed as such.

[113] Instead, the purpose of this recommendation was to include vehicle pursuits in the same teaching tool that is used by police officers to manage subject behaviour and risk and to better explain the existing policy link between vehicle pursuits and the IM/IM.

[114] In such a context, vehicle pursuits should be included in the "lethal force" category to reflect the extreme hazards inherent in the act of pursuing a fleeing driver.

[115] The Commission recognizes that vehicle pursuits are different than other methods included in the IM/IM. Police officers do not wield a pursuit as a weapon or engage in a pursuit with the intention that it result in harm to anyone. However, as discussed in the Commission's Interim Report, vehicle pursuits often result in serious harm or death. By including them in the IM/IM, the Commission had hoped that police officers would be reminded of the tremendous weight and responsibility attached to a decision to engage in a pursuit, similar to the weight and responsibility of other forms of lethal force. The Commission also notes that the recommended policy criteria to engage in a vehicle pursuit are similar to those required for the use of lethal force, thus allowing two distinct areas of policy and training to be conveniently unified.

[116] For these reasons, the Commission reiterates its recommendation.

Interim Recommendation No. 7: That the RCMP Incident Management/Intervention Model refresher training include training on vehicle pursuits.

[117] RCMP members currently receive regular refresher training on the IM/IM. Given the Commission's recommendation that vehicle pursuits be included in the IM/IM, the Commission further recommends that the members' regular IM/IM refresher training include training on RCMP pursuit policy.

[118] This training should ensure that members apply the same risk assessment model to the decision on initiating a police pursuit as they do to the use of lethal force.

[119] Assistant Commissioner White did not support this recommendation due to his opinions expressed with respect to Interim Recommendation No. 6. However, he did indicate that he agreed with exploring the possibility of a recurring recertification process for emergency vehicle operation, outside the confines of IM/IM training.

[120] The Commission accepts this position and modifies its recommendation as follows:

Recommendation No. 7: That the RCMP develop a recurring recertification process for emergency vehicle operations including vehicle pursuits.

Interim Recommendation No. 8: That RCMP national policy be amended to clearly prohibit vehicle pursuits unless the member reasonably believes that a vehicle occupant has committed or is imminently about to commit a serious indictable offence of violence against another person and the risks to the public in not immediately apprehending the suspect outweigh the risks to the public, the police, and the suspect in continuing the pursuit.

[121] The current RCMP policy regarding vehicle pursuits includes a list of offences for which a vehicle shall not be pursued. That list includes:

4.1. A pursuit will not be initiated for the following types of offences:

4.1.1. taking a motor vehicle without the owner's consent as defined at sec. 335, CC;

4.1.2. theft of a vehicle as defined at sec. 334, CC;

4.1.3. possession of a stolen vehicle as defined at sec. 354, CC;

4.1.4. flight from police as defined at sec. 249.1, CC or dangerous driving as defined at sec. 249, CC, when the only evidence of either offence is gained while conducting a vehicle stop or closing the distance;

4.1.5. a violation of a federal traffic regulation;

4.1.6. a violation of a provincial statute or provincial regulation offence;

4.1.7. a violation of a municipal bylaw offence; and

4.1.8. a property-related offence in general.Footnote 23

[122] The Commission agrees that the above list of offences does not justify the risk of a pursuit. However, such a list leaves out many other offences that would also not justify the risk of a pursuit. Given that the Commission has recommended that vehicle pursuits be classified as a "lethal" use of force, it follows that such force must only be used in exceptional circumstances where life is at risk. Accordingly, given the wide variety of criminal offences, it is easier to articulate those where a pursuit may be justified instead of listing those where it would not be.

[123] In light of this and the previously cited broad base of academic research supporting a drastic reduction in vehicle pursuits, the Commission recommends that RCMP national policy be amended to include a blanket prohibition on pursuits except for those situations where there is an imminent risk to the public. The Commission's finding provides the recommended wording for such a policy.

[124] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Of all the Commission's recommendations in this matter, this was its most significant and offers the greatest hope at establishing a clear and practical guide for front-line police officers on the expected standard to apply in vehicle pursuits.

Interim Recommendation No. 9: That the RCMP research emerging technologies such as GPS tracking devices, unmanned aerial vehicles, and electronic vehicle immobilizers to develop effective and safer alternatives to vehicle pursuits.

[125] Given the dangers inherent in police pursuits, the RCMP must prioritize alternative methods to apprehend even those who would otherwise meet the criteria in the recommended policy amendments.

[126] Although research has demonstrated that helicopters offer an impeccable record of safely apprehending fleeing suspects,Footnote 24 the Commission recognizes that the rural nature of RCMP policing does not make helicopter support economical in most regions.

[127] Emerging technologies such as GPS tracking devices that can be quickly deployed, unmanned aerial vehicles that can offer quick and affordable aerial surveillance, and electronic vehicle immobilizers all appear to warrant study.Footnote 25

[128] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Accordingly, it is included in the Commission's Final Report without additional comment.

Interim Recommendation No. 10: That the RCMP amend national policy to require the completion of the Subject Behaviour/Officer Response form for all vehicle pursuits, including abandoned pursuits. To accomplish this recommendation, the RCMP must amend the form to include the relevant situational factors relative to a vehicle pursuit.

[129] Although the Commission was able to review statistics and research from the United States pertaining to police vehicle pursuits, a dearth of information relating to the Canadian experience was noted. For instance, there is no collection or reporting of pursuit-related injuries or fatalities at a national level in Canada.

[130] Without solid data, it is difficult to track the effects of policy changes. Evidence-led policing requires that accurate statistics be collected and made available to researchers and oversight bodies.

[131] RCMP national policy currently requires the completion of a Subject Behaviour/Officer Response (SB/OR) form when certain types of force are used. For instance, the completion of the form is necessary when a conducted energy weapon (e.g. a Taser) is used in any fashion in an incident, whether the weapon was actually fired or not. The form requires detailed information concerning the factors that led to the use of force. This allows the RCMP to investigate trends on a national level and to better implement evidence-led policy.

[132] Given the Commission's recommendation to add vehicle pursuits to the IM/IM, the Commission also recommends that the SB/OR form be updated to allow for submissions for vehicle pursuits. This would replace the forms currently used at a divisional level and allow for national collection and aggregation of data.

[133] Assistant Commissioner White did not support this recommendation but supported adding the situation factors contained in the RCMP's SB/OR report to the existing vehicle pursuit report.

[134] The Commission is satisfied that this approach achieves the same objective and supports the RCMP's solution. Accordingly, this recommendation is modified as follows:

Recommendation No. 10: That the RCMP amend its vehicle pursuit reporting form to include the relevant situational factors that are contained in the RCMP's Subject Behaviour/Officer Response report.

Interim Recommendation No. 11: That the RCMP publish an annual report with detailed statistics gathered from the aggregated pursuit data, including the number of pursuits initiated, the outcome of those pursuits, the number of collisions, injuries, and fatalities as a result, and the ultimate judicial outcomes.

[135] As a corollary to Recommendation No. 10, the Commission recommends that the RCMP publish the aggregated pursuit data for the benefit of the Commission and other researchers.

[136] Assistant Commissioner White supported this recommendation. Accordingly, it is included in the Commission's Final Report without additional comment.

Conclusion

[137] The circumstances of this report and the death of Mr. Duarte are without question very tragic. This report cannot bring back what was lost through the criminal actions of one person. However, the Commission is optimistic that a modernization of RCMP policy and procedures related to checkpoints and vehicle pursuits combined with additional training can result in safer practices that will reduce the risks to police, the public, and suspects alike when police engage in traffic enforcement operations.

[138] The Commission makes its final findings and recommendations as follows:

Finding No. 1: The RCMP members involved in the events of October 29, 2012, failed to comply with "E" Division Operational Manual policy, which required members to ensure that safety precautions were taken.

Finding No. 2: Corporal Davies failed to properly supervise the traffic checkpoint operation.

Finding No. 3: Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng engaged in a pursuit contrary to policy due to ambiguity in the RCMP's pursuit policy.

Finding No. 4: Corporal Davies failed to direct Constable Johnston and Constable Cheng to discontinue their pursuit due to ambiguity in the RCMP's pursuit policy.

Finding No. 5: The RCMP national policies relating to traffic checkpoints are inadequate.

Finding No. 6: The RCMP national policies relating to police vehicle pursuits are inadequate.

Recommendation No. 1: That RCMP national policy be amended to provide specific guidance on the set-up of police checkpoints to minimize the risk of vehicle pursuits, including the use of an escape prevention vehicle and the use of fully marked police vehicles when available.

Recommendation No. 2: That the RCMP provide additional training to any regular member involved in checkpoint operations on how to plan vehicle checkpoints so as to minimize the risk of pursuits and vehicle collisions. This training should also emphasize alternative methods of enforcement.

Recommendation No. 3: That RCMP national policy be amended to remove the concept of "closing the distance" in the context of police pursuits. "Closing the distance" should refer only to police emergency driving involving routine violator apprehension where there is no indicia of a driver's attempt to flee.

Recommendation No. 4: That the definition of a "pursuit" in RCMP national policy incorporate the concept that a pursuit begins once the driver of a subject vehicle takes any evasive action to distance the vehicle from police, regardless of whether police emergency equipment has been activated on the police vehicle(s) involved in attempting to intercept the subject vehicle.

Recommendation No. 5: That RCMP national policy impose a requirement on members to immediately discontinue attempts to stop a vehicle once the pursuit definition is met, unless the pursuit may continue pursuant to criteria outlined in the policy. (The criteria is proposed in Recommendation No. 8.)

Recommendation No. 6: That the RCMP Incident Management/Intervention Model be amended to include vehicle pursuits under the "lethal force" category.

Recommendation No. 7: That the RCMP develop a recurring recertification process for emergency vehicle operations including vehicle pursuits.

Recommendation No. 8: That RCMP national policy be amended to clearly prohibit vehicle pursuits unless the member reasonably believes that a vehicle occupant has committed or is imminently about to commit a serious indictable offence of violence against another person and the risks to the public in not immediately apprehending the suspect outweigh the risks to the public, the police, and the suspect in continuing the pursuit.

Recommendation No. 9: That the RCMP research emerging technologies such as GPS tracking devices, unmanned aerial vehicles, and electronic vehicle immobilizers to develop effective and safer alternatives to vehicle pursuits.

Recommendation No. 10: That the RCMP amend its vehicle pursuit reporting form to include the relevant situational factors that are contained in the RCMP's Subject Behaviour/Officer Response report.

Recommendation No. 11: That the RCMP publish an annual report with detailed statistics gathered from the aggregated pursuit data, including the number of pursuits initiated, the outcome of those pursuits, the number of collisions, injuries, and fatalities as a result, and the ultimate judicial outcomes.

[139] Pursuant to subsection 45.72(2) of the RCMP Act, the Commission respectfully submits its Final Report, and accordingly the Commission's mandate in this matter is ended.

Guy Bujold

Interim Vice-chairperson and

Acting Chairperson

- Date modified: